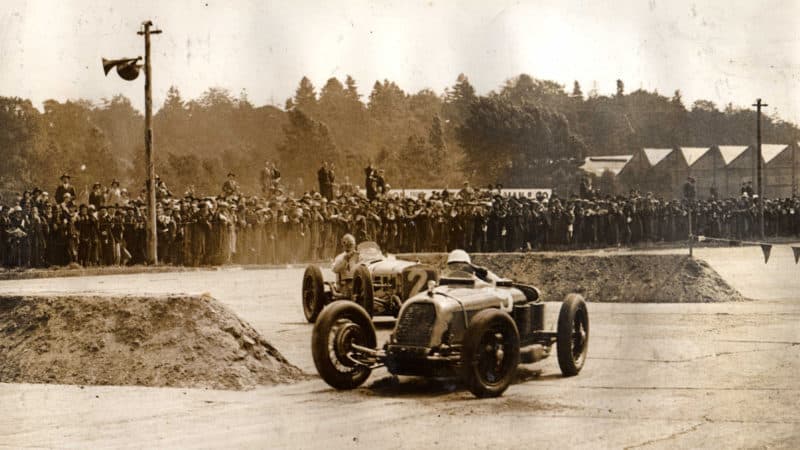

“Henry Segrave’s Talbot exhaust pipe belched wicked yellow flames in the most ominous manner without apparently affecting his speed; Robert Sénéchal appeared to delight in violent skidding on all the corners, whereas all the other drivers restrained themselves from this amusing and destructive policy; it was interesting to note that Segrave and Albert Divo shot away from Robert Benoist’s Delage on leaving the last sandbank, but owing to unreliable brakes and lack of faith in their front axles, they cut out much earlier than Benoist, approaching the bends, so that the Delage lost no ground to them on the whole lap.”

No Lewis Hamilton/Max Verstappen-style shenanigans, of course – but the drivers still had their moments. “The crowd now settled down to watch the extraordinary skids performed by Robert Sénéchal, who seems to delight in this method of cornering,” Motor Sport tells us. “One of the most exciting incidents of the race occurred at the second series of bends: Sénéchal was being closely followed by Divo, who was usually most unspectacular; on the right-hand turn Sénéchal skidded broadside, nearly stopping in front of Divo; in perfect time Divo executed an exactly similar skid, checking his car when it was parallel to the Delage; both cars then proceeded to turn left on to the main track, where the same thing took place again, except that Divo slipped past Sénéchal on the inside and stole a useful lead.

“Just before 90 laps Benoist came in to try and rectify various troubles, and [Louis] Wagner took the lead on Sénéchal’s Delage. Benoist’s car was on fire, and spent some time at the pits, eventually restarting in the hands of André Dubonnet, an amateur, who drove in his ‘gent’s natty suitings’ and hatless!” In blue lounge suit, Dubonnet had no experience of the layout but gamely picked up the challenge of subbing for future WWII resistance hero Benoist. Such were the casual-in-attitude, formal-in-attire heroics of pioneering motor sport.

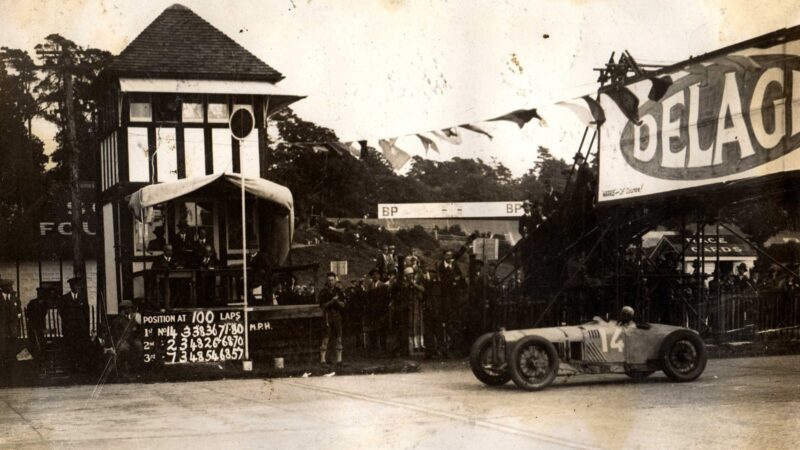

“Wagner was soon in trouble with his feet, and stopped every few laps to bathe them, but managed to retain an ever decreasing lead,” Motor Sport continues. “Divo in the meantime stopped once more, and after many fruitless attempts to restart [his Talbot] eventually gave up, thus eliminating the last British hope. Excitement rose to fever pitch during the last 15 laps, with Campbell gradually overhauling the crippled and flaming Delage driven by Dubonnet, who was evidently suffering greatly, tongues of flame belching from the bonnet. Both these cars, however, were catching up Wagner’s Delage, which kept on stopping on account of the driver’s feet. On the 102nd lap the Bugatti passed the Delage, thus securing second place, which it maintained to the end. Wagner was too far ahead to be caught, and eventually won at 71.61mph, a remarkably good speed considering the number of stops.”

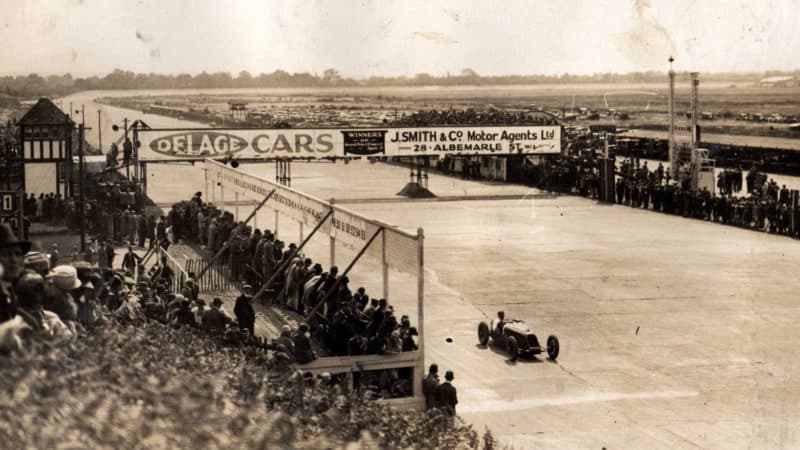

Delage of Sénéchal and Wagner could not be caught

Brooklands Museum

Thus were British hopes vanquished by the French that day at Brooklands, although Segrave – whose Talbot dropped out plagued by engine and brake problems – claimed the Stanley Cup for fastest lap, at 85.99mph.

For Louis Delage, victory didn’t assuage his frustrations over his cars’ heat troubles that left mechanics wrapping asbestos around exhausts to stop them burning through bodywork and soles of feet. He chose not to enter the final round of the World Championship at Monza in September as his engineers turned the 15S8 engine through 180-degrees, moving the exhaust pipes away from the driver. The redesign triggered a dominant 1927 for Delage which claimed the final world title to be awarded before the ‘reboot’ in 1950. There was no drivers’ title back then, although that didn’t stop the French press dubbing their darling Benoist ‘world champion’ in a year he was also awarded a Chevalier of the Legion d’Honneur. Scenes at Brooklands a year earlier contributed to his enduring legend.

Wagner, Sénéchal, Dubbonet, Benoist, Campbell, Segrave… Distant motor racing figures who in some sense seem familiar, in another as if they from another world. But head down to Brooklands on Saturday and listen closely: their echoes still linger.

Race starts display will see cars blasting on to the banking

Brooklands Museum