The particular aero development path each team has chosen will also impact how effectively they can counter the problem. Those that have designs optimised to run as close to the ground as possible will likely have more issues that those who have pursued a path of slightly higher ride heights and greater use of airflow off the side of the floor to seal the underside.

Of course, active suspension, which effectively allows for the ride height of the car to be set regardless of bump compliance and other factors would make the problem go away, as suggested by Mercedes’ George Russell.

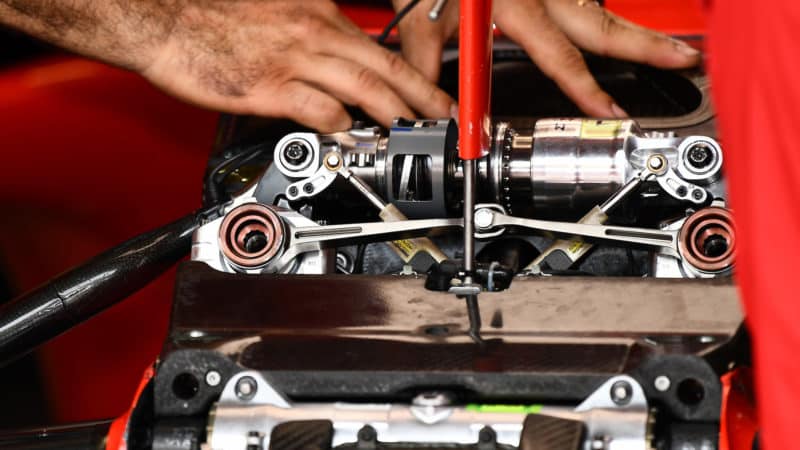

The idea of a ‘spec’ active system for F1 was discussed in FIA working groups a couple of years ago, but dismissed in favour of greatly simplified passive systems. While it is easy to say, ok, everyone run this standard system, in practice, development would take time and no single solution could be bolted into every car. Each team (with the possible exception of those who have chosen the customer route to suspension components) will have their own damper designs, as well as very different mounting points, rockers and suspension motion ratios. Not to mention Red Bull and McLaren with their pull rod front set-ups. All of which are intrinsically tied to the packaging of their cars. Any active system would also need its own bespoke control electronics, which again opens the can of worms around how far teams can go with coding and developing their own software.

This would mean, as pointed out by various technical directors including McLaren’s James Key and AlphaTauri’s Jody Egginton, not insubstantial costs and a prolonged development process. Any such system would be at least one, and more likely two years in the making, by which point, the combined brain trusts of each team will have likely come up with passive solutions. One then has the fact that even spec active suspension would invariably lead to much faster lap times, with knock on effects in terms of tyre performance and even (if things got really out of hand) track safety limits. No doubt teams would love to have the flexibility of active control, but their attentions and resources will be all be dedicated to the tools they currently have. As Key summed up, “As a technical director, I’d love to see the return of active suspension personally. But, with the cost cap, it’s not the best project to be doing.”