MPH: To the man trying to fill Christian Horner's shoes: good luck!

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

Italy 1971 has to be high on any list: because it was the last race at Monza before chicane blight, because five drivers crossed the line within six-tenths of a second, and because, with a winner’s average of 150.754mph, it is still the fastest F1 race ever run.

When the drivers arrived there the World Championship had already been clinched by Stewart, so all that was at stake was victory in one of the season’s most prestigious Grands Prix.

Highly favoured at such a fast circuit were the ‘twelves’ of Ferrari and BRM: less fancied was the only other such, the lone Matra of Amon. How so? Because although the shrieking French V12 made a glorious sound, it invariably fell short on power: so hopeless had Chris’s engine been at the Nürburgring that the team skipped the Austrian GP, and concentrated on resolving its oil churning problem.

This it achieved, so now Amon had an engine perhaps not on par with Ferrari and BRM, but at least a match for the ubiquitous Cosworth DFV.

Late in Saturday afternoon qualifying Ickx’s Ferrari was shown as fastest, and only after the local papers had gone to press did the authorities concede that someone had gone quicker: Amon in the revitalised Matra, no less, complete with the tiniest rear wing ever seen on an F1 car.

If the tifosi were disappointed by that on race morning, they were soothed at the start, when Regazzoni’s Ferrari left before the rest, and screamed by in the lead at the end of lap one.

Early on, though, Peterson’s March was in front, hounded by the Tyrrells of Stewart and Cevert, Siffert’s BRM, Regazzoni and Ickx. At Monza the attrition rate was always high, and before halfway Stewart was gone, together with both Ferraris, while Siffert found himself stuck in fourth gear.

Others, though, were coming into play, not least Hailwood, returning to F1 with Surtees after six years away. On lap 25 Mike – having qualified 17th – came by in the lead: “I didn’t know what this slipstreaming lark was all about – I’d never done it before…”

As the race progressed Amon’s Matra ran easily in fifth or sixth, but on lap 36 Chris decided it was time to go, at which point the Matra assumed the lead, and looked set.

Until lap 47, that is, when Amon came by in third place – and shielding his eyes. “I’d been losing tear-offs,” he said, “so this time I’d taped it on more firmly – so firmly that when I pulled it off the whole bloody visor went! Actually, it didn’t make a lot of difference, because then I started to get fuel starvation, as well…”

While the Matra fell away to sixth, where it finished, those ahead concentrated on the final sprint to the flag, on being in the right place at Parabolica. As it was, Cevert and Peterson arrived there side by side, braking too late and sliding wide – whereupon Gethin’s BRM snicked by the pair of them, and stayed there to the flag.

“The rev limit was 10,500,” said Peter, “but I took it to 11,500 before snatching top gear, figuring the bugger would probably blow apart – but if it didn’t I’d win!”

Over the line he was a couple of feet ahead of Peterson, with Cevert third, Hailwood fourth and Ganley’s BRM fifth. I was at the line as they went over it in a blur: I hadn’t a clue who had won. NSR

About 100 Greatest Grands Prix | From the editor Damien Smith

The Grand Prix motor races we can never forget…

This was a special one-off magazine, dedicated to our love of Grand Prix racing and produced by the same team that brings you Motor Sport each month.

It seemed a good idea: whittle down 107 years of racing history to come up with 100 GPs that could be considered the ‘greatest’ – then rank them in meritocratic order. By week three, the old grey matter was beginning to ache…

Defining greatness was the first task. There were the obvious races – the wheel-to-wheel duels, the comeback classics. But there were also individual performances of supreme dominance, races that might not necessarily have been the most exciting to witness. Greatness goes way beyond thrill-a-minute, we decided.

Choosing which races should make the list was hard enough; ranking the top 100 in some sort of order was even tougher, especially when it came to the crunch: which should be number one? We never did agree unanimously on the ‘greatest’, but if the magazine was to be finished a decision had to be taken. And that’s what I’m here for!

Will you agree with our choice and order? Probably not. But if steam begins to issue from your ears, take a deep breath. In any exercise such as this, there is no definitive list – because there can’t be. Our top 100 is based on opinion, nothing more, designed to be a bit of fun and to spark good-natured debate among fans of the world’s greatest sport.

You can download 100 Greatest Grands Prix in PDF form in the Motor Sport app.

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

Former McLaren F1 team-mates Mika Häkkinen and David Coulthard are set to renew old rivalries in a new Evening with... tour – they told James Elson all about it

In Formula 1, driver contracts may look iron-clad on paper, but history shows that some of its biggest stars have made dramatic early exits

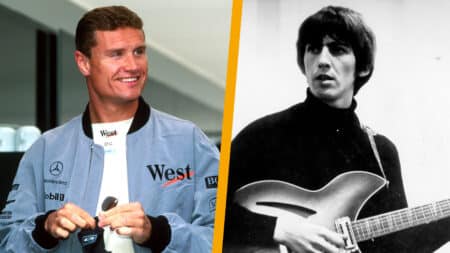

Former McLaren F1 ace told James Elson about his private audience with The Beatles' George Harrison, who played an unreleased grand prix-themed song