MPH: To the man trying to fill Christian Horner's shoes: good luck!

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

The numbers behind Lewis Hamilton’s Formula 1 rivalries with team-mates past and present

With the dust well and truly settled upon the 2017 season but the opening race of 2018 still so far off, it’s a good time to look at some of the notable team-mate comparisons in more detail. Not just the numbers, but the underlying factors that drove them. The relationships – between car and driver, team and driver, driver and driver – and their correlation on performance are complex and not widely appreciated. They encompass the physiological factors that determine raw talent but also how that dovetails with the traits of a particular car on a given day. They encompass the psychological and the intellectual and they encompass all the ‘known unknown’ variables in between. There is not a hard-wired, unchanging, hierarchy of overall ability and the circumstances of any given moment play heavily upon the competitive reality. Within that framework, here we focus on the comparison between the Mercedes drivers Lewis Hamilton and Valtteri Bottas, with the performance of previous Hamilton team-mates for perspective.

A highly regarded young driver getting his big break into the best team in the business after an apprenticeship at Williams – that was the good news for Valtteri Bottas. The bad was that he’d be measured against an incumbent multiple world champion. That was never going to be easy and it wasn’t, even though it allowed Bottas the opportunity to take his first three Grand Prix victories. As a generality, he didn’t offer the season-long consistent threat to Hamilton that Nico Rosberg had provided and didn’t have Nico’s taste for psychological warfare – and this in part allowed Hamilton access to a higher plane than before, no longer wracked by the competitive paranoia that Rosberg had induced in him. Hamilton was much more at ease within the team than before.

As for the specific pattern of their performances, it was painted upon the canvas of a car that was particularly tricky to get the best from. The Mercedes W08 had underlying issues of balance. On any circuit where there was a big difference in speeds between the important corners, it couldn’t be adequately balanced over the lap – in such cases it would generally be oversteery through the faster corners and understeery through the slow ones. There wasn’t a great deal of workable range in set-up with regard to covering more than one tyre compound through the weekend and it was generally closer to overworking its rear tyres than either the Ferrari or Red Bull.

What such a car required from the driver was a great feel for rotation – getting the car turned early, preferably with the minimum of steering lock – feeling and anticipating the weight transfer, manipulating it to aid direction change without the time-consuming and tyre-wearing effects of lots of lock. When the car was working well, and on a tyre to which it was suited, Hamilton was able to combine this very subtle skill with his usual super-late and hard braking. By comparison, Bottas could either a) brake earlier to give himself more time to get the car rotated around the outer front tyre or b) use more steering lock. Either way, he would be losing lap time to Hamilton. That ability to rotate by using the brakes within the blink-brief window of very late braking was crucial and Hamilton was simply better at it. So Bottas would make more steering inputs, manhandling the car in the initial part of the turn more than Hamilton. It scrubbed off more speed, it took more from the front tyres.

However, when the car was raced upon tracks with a very low grip surface – typically with the finely-grained tarmac found at Sochi, Monaco, Austria, Hungary, Mexico and Abu Dhabi – its limitation was the front end. The front tyres did not load up quickly enough, wouldn’t allow Hamilton to adequately rotate the car into the slower corners. With the car like this, he lost his inherent advantage over Bottas. Furthermore, he would frequently compensate by trying yet-harder to prise that braking/cornering overlap open – which would make the problem even worse. This was what happened at Sochi, Baku and Monaco. Bottas, just accepting that the front end wasn’t working, simply incorporated it into his approach, and was clearly faster than Hamilton at those tracks. There was less adjusting for Valtteri to do and he hadn’t really stepped his performance up so much as Hamilton had dropped off. Later, with guidance from the engineers, Hamilton was more able to contain his approach when appropriate and accept that on such tracks he wouldn’t have his usual advantage over Bottas – because those last couple of tenths were contained in an area of the car’s performance map that was just not accessible on low grip surfaces.

In 14 of the 20 races, the team was able to get the car into its narrow operating window and on those occasions, Hamilton generally carried big chunks of advantage in qualifying pace (i.e. when he was faster, it was often a lot faster. Five times his advantage was half-a-second or more). Furthermore, he could more easily get the tyres to stay in shape to make longer stints more feasible, giving greater strategic flexibility. As these various phases of circuit types and the championship battle played out, Bottas’ consistency suffered. Generally, he was more competitive in the first half of the season than the second and his confidence seemed to take a knock when he was told at Spa that he would be supporting Hamilton’s title challenge for the balance of the season. When this coincided with perhaps Hamilton’s most devastating turn of speed of the season – his qualifying lap there was way beyond the norm – it was a double confidence blow for Bottas and it took some time before it returned (at the low grip surface of Mexico). There was a feeling within the team that once Hamilton had secured the title, he wasn’t quite at the same competitive pitch as before and this together with Bottas’ renewed confidence gave Valtteri a strong end of the year, with two consecutive poles and victory in the final race.

Prior to the 2017 season, Bottas might secretly have hoped that he’d be instantly at Hamilton’s level once he was in the same car but admits he didn’t really believe that would be the case. He understood there would be much to learn – and this realisation was only deepened when he actually got to try the car and work with the team, both of which were much more complex than anything he’d experienced before. So he worked away at learning the nuances and when the opportunities arose, he used his strengths – notably an uncanny ability to absorb pressure – to deliver. That won him both Sochi and Abu Dhabi. His other win – in Austria – came by ruthlessly anticipating when the start lights would go out to ensure victory over Vettel’s Ferrari.

As a starting point against an all-time great driver at the height of his powers and already ensconced in the team, Bottas’ season was more than respectable. But it was less than was achieved by Jenson Button in similar circumstances in 2010.

Looking just at the qualifying performance, Bottas’ deficit to Hamilton was almost identical to the three-season average of Button’s, and significantly adrift of the four-season average of Rosberg’s (who was much closer). But in looking at race day performance, Bottas beat Hamilton in only 15.8 per cent of the races where a comparison was possible whereas Button beat Hamilton in 38.7% of the races they contested as McLaren team-mates (again, where a straight comparison was possible). In fact, Button’s winning ratio against Hamilton was actually slightly better than Rosberg’s (34.5%) despite the latter’s greater qualifying speed. Heikki Kovalainen, in his two seasons alongside Hamilton, beat him in 34.8% of comparable races (about the same as Rosberg managed) but was slightly further adrift than Button in qualifying. All those comparisons pale alongside Alonso’s who beat (a rookie) Hamilton six times to five in the races where a straight comparison was possible and qualified marginally quicker when account was taken of varying fuel loads (race fuel Q3 was the system used in 2007).

Even if the prospect of Bottas ever providing Hamilton with the sort of in-team challenge represented by Alonso look remote, to at least become a real stone in Hamilton’s shoe – in the way that Button and Rosberg did – requires Bottas to join up his best bits more consistently.

| Year | Driver | % difference | Time difference | Head-to-head |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | Bottas | Hamilton 0.29% faster | 0.254sec | 13-5 |

| 2016 | Rosberg | Hamilton 0.169% faster | 0.141sec | 11-3 |

| 2015 | Rosberg | Hamilton 0.144% faster | 0.131sec | 11-7 |

| 2014 | Rosberg | Hamilton 0.027% slower | 0.023sec | 7-5 |

| 2013 | Rosberg | Hamilton 0.036% faster | 0.032sec | Rosberg 6-5 |

| 2012 | Button | Hamilton 0.35% faster | 0.314sec | 13-1 |

| 2011 | Button | Hamilton faster by 0.237% | 0.207sec | 12-4 |

| 2010 | Button | Hamilton 0.288% faster | 0.255sec | 14-3 |

| 2009 | Kovalainen | Hamilton 0.302% faster | 0.274sec | 8-2 |

| 2008 | Kovalainen | Hamilton 0.332% faster | 0.291sec | 7-6 |

| 2007 | Alonso | Hamilton 0.016% slower | 0.014sec | 7-7 |

| Driver | Difference in qualifying pace | Difference in race results |

|---|---|---|

| Valtteri Bottas (one season) | Hamilton faster by 0.29% | Bottas beaten in 84.2% of races |

| Nico Rosberg (four seasons | Hamilton faster by 0.081% | Rosberg beaten in 65.4% of races |

| Jenson Button (three seasons) | Hamilton faster by 0.292% | Button beaten in 61.3% of races |

| Heikki Kovalainen (two seasons) | Hamilton faster by 0.317% | Kovalainen beaten in 65.2% of races |

| Fernando Alonso (one season) | Hamilton slower by 0.016% | Alonso beaten in 45.45% of races |

* Imprecise because of varying fuel levels in Q3 in that season

** Only qualifying and races where direct comparison possible have been included in these numbers. So retirements or different spec cars, for example, not included. Nor qualifying sessions held on a wet but drying track where track positioning was disproportionately crucial.

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

Former McLaren F1 team-mates Mika Häkkinen and David Coulthard are set to renew old rivalries in a new Evening with... tour – they told James Elson all about it

In Formula 1, driver contracts may look iron-clad on paper, but history shows that some of its biggest stars have made dramatic early exits

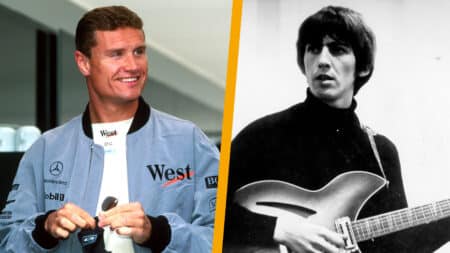

Former McLaren F1 ace told James Elson about his private audience with The Beatles' George Harrison, who played an unreleased grand prix-themed song