MPH: To the man trying to fill Christian Horner's shoes: good luck!

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

There are obvious parallels between Ferrari’s 2014 season and that of 1991. In both cases the team boss left part-way through the year and was replaced by a man who then opted not to continue with arguably the team’s biggest asset, its superstar lead driver. Even more bizarrely, the new boss was gone within weeks of losing the driver, replaced by yet another boss.

Going into ’91 team boss Cesare Fiorio and Alain Prost were openly hostile, this going back to the latter being quoted the previous year as saying Ferrari didn’t deserve to win the championship after Fiorio refused to apply team orders to aid Prost’s cause. Into ’91 championships weren’t the bone of contention – the Ferrari 643 was not a car even Prost could make into a race winner, let alone a title challenger. Fiorio was fired mid-season, replaced by Marco Piccinini, who was presiding over the running of the team when Prost was fired, ostensibly for daring the criticise the car. A few weeks after that and Piccinini was gone – to be replaced by Luca di Montezemelo. The parallels with 2014 are remarkable, are they not?

The circle of time has taken 23 years to complete a full revolution. In 2014, substitute the F14T for the 643, di Montezemelo for Fiorio, Fernando Alonso for Prost, Marco Mattiacci for Piccinini – and Maurizio Arrivabene for di Montezemelo! It illustrates that things work in a very specific way at Maranello regardless of who the actual people are. The dynamics of Italian corporate politics remain the same and the pressure for the team to be competitive is enormous; both from within Italy and from the powers of F1. More than any other team, a fall from competitive grace is intolerable. Its name carries too much weight for that to be OK.

But in 2014 there has been an additional pressure: the floatation of the Fiat-Chrysler group on the New York stock exchange. Ferrari is the halo brand of that corporation, F1 is the main shop window for Ferrari. It was a bad, bad time to be seriously under-performing, potentially costing billions. Had it been competing at the level it did at any time from 2008 onwards – competitive and race-winning even if the world title proved narrowly elusive – the team could probably have withstood this level of scrutiny. But the F14T was too far off for that to be possible and so the structure began to buckle.

Just as in ’91, the instrument of that pressure was the management of parent company Fiat; substitute Sergio Marchionne for Gianni Agnelli. Into such a combustible mix, having one of the world’s greatest drivers trying only to get things how he needed them to be from a racing perspective provided the lethal spark. Alonso, just like Prost, was seeing the prime time of his career being squandered by poor management decisions and was feeling understandably frustrated and powerless. Alonso, just like Prost, responded by demanding more of a say in how things were run.

The Ferrari management of 2014 – just as that of 1991 – could not tolerate, nor be seen to tolerate, such a threat to their authority when they themselves were under such scrutiny. Furthermore the very stature of the driver, the widespread recognition of his level as one of the greatest, was only adding to the intolerable pressure upon the under-performing team. So Mattiacci let Alonso go, just as Piccinini had done Prost. For reasons seemingly unrelated to the loss of the driver, Fiat then decided it had an agenda for Ferrari that someone else could better fulfil than the current chief. Lots of blood and intrigue, just as in all the best Italian dramas.

There are a couple of crucial differences this time around – and the following comes from talking to many of those involved behind the scenes on condition of non-attribution (i.e. OK to use the information, but not to be quoted). One difference between the 1991 and 2014 situations is that Alonso had already been trying to leave the team. However, by the time of Montezemelo’s departure Fernando was beginning to think he might be better placed staying around for at least another year. The logic of that thinking was easy to understand: there was nothing available in 2015 at Red Bull or Mercedes, the obvious prime seats for him.

His manager Flavio Briatore had through the summer tried in vain to engineer an exchange deal – Lewis Hamilton for Alonso between Mercedes and Ferrari – that foundered on Mercedes boss Toto Wolff not wanting to disturb the equilibrium of the Hamilton/Rosberg line-up. For all that they had their competitive niggles this year, there was no poison between Lewis and Nico; neither of them has the sort of dominating personality that leads to that. Bringing Alonso in would, believed Toto, have ramifications upon the functioning of the team that didn’t fit in with how he wanted to run things.

Furthermore, Hamilton himself would have been unlikely to have agreed to the deal even had it been suggested to him. As Briatore had been working on this deal, Mattiacci was trying to get Alonso to extend for an extra three years beyond 2016. The Ferrari boss absolutely understood the value of having arguably the world’s number one driver on side, but Alonso consistently declined to take up the extension offer.

Alonso was therefore left with the McLaren option. One year deal, suggested Fernando. Multi-year or no deal responded Ron Dennis. That potentially left Alonso out of sync should a Mercedes seat become available after the end of 2015, as Hamilton’s current contract expired.

So there was a very sound logic to his trying to repair the bridges at Ferrari, to stay there for one more year. Besides, the 2015 Ferrari has every chance of being much more competitive than the F14T; the more obvious of the power unit’s shortfalls are an easy fix but just couldn’t be done during the season because of the homologation rules whilst the car itself will be the first to have been conceived from the start under the aegis of James Allison, the gifted technical director.

Hence Alonso’s meeting with Mattiacci between the Singapore and Japan races. But going into that meeting there was a vital piece of information Alonso and his manager did not possess, but Mattiacci did: Sebastian Vettel – who had a long-term informal agreement that he would give Ferrari first call on his services should he leave Red Bull – had a clause in his Red Bull contract that would allow him to leave a year earlier than its full term (which was until the end of 2015) if he was below third in the championship before a specified cut-off date. That contractual window was about to close shortly after the Japanese Grand Prix. Alonso and Briatore incorrectly assumed that Vettel was committed to Red Bull until the end of 2015.

A couple of weeks prior to the Alonso/Mattiacci meeting, Briatore had been angrily demanding that Mattiacci honour the agreement made between Alonso and Montezemelo that Fernando could be released at the end of this season if he so wished. Mattiacci was saying that the contract ran until the end of 2016 and was watertight, with no options on Alonso’s side. When he had signed this contract a couple of years earlier, Alonso had the choice of a very lucrative contract with get-out clauses on his side or an even more lucrative one that offered him no such choices. He’d opted for the latter. Briatore insisted this had now been rendered obsolete by Montezemelo’s verbal and handshake agreement that Fernando could walk at the end of ’14, if he chose to. Even though Montezemelo was no longer there, the agreement had been reached when he represented Ferrari.

That’s where things stood as Alonso and Mattiacci had their showdown meeting. Fernando suggested he would be prepared to continue on his current contract that ran until the end of ’16 – but with a few amendments: 1) Exit clauses that gave him certain windows – like Vettel’s Red Bull contract – to leave at the end of each season if he was below third in the championship at the cut-off date. 2) A veto over the choice of the other driver. 3) An option to choose technical staff.

Mattiacci – a man used to having control over his employees, not forming partnerships with them or being dictated to by them – did not find any of these demands acceptable. Rather than giving yourself get-out clauses, he suggested, I’d like to see more commitment, not less. By this he meant extending beyond ’16. Fernando – who has given incredible commitment to a less than fully competitive Ferrari for five years – did not like the suggestion of him being less than fully committed. He reacted angrily. Mattiacci said that if he did not wish to continue either on his current contract or an extension of it, Ferrari would now honour the agreement made by Montezemelo, i.e. Fernando was free to leave, without either side owing the other. Briatore suggested Alonso sign the memorandum of understanding for the release, believing Mattiacci would then back down. He didn’t.

Instead Mattiacci contacted Vettel and told him that if he was ready to sign, so was Ferrari. Red Bull announced at Suzuka that Vettel was leaving and Red Bull’s Christian Horner revealed that “Ferrari had made Sebastian a very generous offer”. It was only at this point that Alonso finally had all the pieces of the jigsaw – and further words were exchanged between him and the team boss.

There have since been suggestions that there was an overlooked clause in the Ferrari/Alonso contract that did not allow the team to be in negotiations with other drivers before the end of the season without informing Alonso first – and that therefore Ferrari was in breach and this might be used as leverage by Briatore/Alonso to have him do one more year at Ferrari, after all. But if that was so, it’s no longer an option being pursued.

It’s easy to understand the positions of both sides in this whole dispute. But against the bigger backdrop of the coming floatation and the strategic choices of the Fiat board, it was a minor issue. It is not believed that Mattiacci’s departure had anything to do with his Alonso negotiations. Whatever it was that caused him not to be even given another position within the Fiat empire was unrelated to how he performed his brief role as Ferrari chief.

Which brings us onto the other big difference between 1991 and 2014; F1’s very uncertain future and Ferrari’s position within it. It’s all in a state of flux at the moment. Commercial and technical regulations that were seemingly set until well into the future are now being openly questioned and negotiated over as there comes a belated realisation that the choppiness of the F1 water might be because a very big waterfall is coming. The territory of the future might need to be staked out now.

When Fiat’s Sergio Marchionne announced the recruitment of Arrivabene, there was probably more than just PR speak in what he said: “We decided to appoint Maurizio Arrivabene because, at this historic moment in time for the Scuderia and for Formula 1, we need a person with a thorough understanding not just of Ferrari but also of the governance mechanisms and requirements of the sport. Maurizio has a unique wealth of knowledge. He has been extremely close to the Scuderia for years and, as a member of the F1 Commission, is also keenly aware of the challenges we are facing.

“He has been a constant source of innovative ideas focused on revitalisation of Formula 1. His managerial experience on a highly complex and closely regulated market is also of great importance, and will help him manage and motivate the team. I am delighted to have been able to secure his leadership for our racing activities.”

Laying the stakes for the future – of establishing F1’s income source, distribution and Ferrari’s slice at a time when these projected revenue streams are a part of what shareholders in the Fiat-Chrysler group would be buying – was probably too serious a job to be handled by someone new to the sport.

But it all rather leaves an unsettling thought: as these financial moves are swirling around, who is looking after the race team and what plans are being put in place to make it once more the focused entity it was under Ross Brawn and Jean Todt? History suggests that with such an approach Ferrari can beat the world. Without it, it flounders. And if you doubt the relevance of history, just look at the link between 1991 and 2014.

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

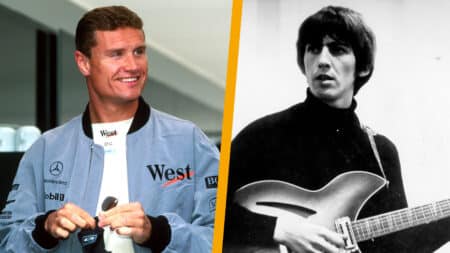

Former McLaren F1 team-mates Mika Häkkinen and David Coulthard are set to renew old rivalries in a new Evening with... tour – they told James Elson all about it

In Formula 1, driver contracts may look iron-clad on paper, but history shows that some of its biggest stars have made dramatic early exits

Former McLaren F1 ace told James Elson about his private audience with The Beatles' George Harrison, who played an unreleased grand prix-themed song