MPH: To the man trying to fill Christian Horner's shoes: good luck!

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

As Renault changes its management, Mark Hughes examines the team’s expectations

The news that Jérôme Stoll is stepping down as president of Renault Sport brings into question the long-term strategy of Renault’s Formula 1 programme. Stoll, aged 65, is to be replaced by Thierry Koskas.

Earlier this year, Renault team principal Cyril Abiteboul said the following: “In my opinion, Renault can afford pretty much anything. Renault is the largest car maker involved in Formula 1 – full stop.

“So we can afford anything as long as it makes sense. Then it’s just a question of value for money and whether it makes sense to spend that, given where we are in the development of our team.”

Renault’s Enstone team operates on a budget somewhere between 60-70 per cent of that of Mercedes or Ferrari. Company president Carlos Ghosn – a notoriously tough financial man – gave his approval to Renault re-entering F1 as a constructor (rather than just an engine supplier) based on certain very well-defined budgetary conditions. The racing arm of the company was able to convince him of the feasibility of Renault being competitive within a five-year time frame within that budget. That was three years ago.

The timing beam doesn’t recognise how much money you’ve saved

While Renault’s Enstone-based team has become steadily more successful since being rescued as little more than a shell – and will this year finish ‘best of the rest’ in fourth place in the constructors’ championship – the raw performance deficit to the big players at the front has changed very little during that time.

The power unit supplied by the Viry part of the operation remains far, far away from those supplied by Ferrari and Mercedes so although Enstone is a ‘works’ team it has to work hard just to beat the likes of Haas and Force India with a significant power disadvantage. In the process, it is not unusual that the Mercedes and Ferraris will lap the Renault before the end of the race.

That is not the sort of performance deficit that will be made up over a winter, but represents an underlying difference of scale in financial commitment.

The loss of Red Bull as a Renault customer has essentially come from it being unconvinced that Renault was prepared to commit the level of investment necessary to be competitive in the hybrid engine era.

More:

“They are trying to fly first class but paying cattle-class rates,” said one well-placed person there. The different scale of Honda’s investment is apparently more than apparent with just the most cursory comparison of the respective engine facilities.

Viry and Enstone are filled to bursting point with talented engineers. But Maranello and Brixworth/Brackley have more – and are able to deploy much more powerful infrastructures and resources. Honda is now aspiring to get to that level, as quickly as possible, in partnership with the extremely well-resourced Red Bull. Which leaves Renault out on a limb.

“Red Bull has been very clear that [Honda] is investing massively, apparently much more than us,” said Abiteboul in Russia. “We are happy for Red Bull and Honda. Frankly we have our way to do things. We have a plan and we are executing that plan. It’s not just about an arms race.”

Maybe so. Maybe it shouldn’t be about who can spend the most. Maybe it’s ridiculous that a budget of 200 million-plus Euros should be inadequate to race two cars 21 times a year. But that’s the environment in which Renault has chosen to compete, a very public theatre of excellence with trials held every two weeks highlighting everyone’s competitive merit. If Renault has chosen to do it with one arm behind its back because it doesn’t feel that doing it with two is financially reasonable, then what has happened for the last five years of the hybrid formula – i.e. Renault being consistently outclassed by its bigger-spending rivals – will surely just continue.

“We don’t have the sort of very complex full car dyno to test the engine in its ultimate environment,” said Abiteboul. “That’s something we are looking at. We think it’s a bit unreasonable to have to invest in such equipment but if we have to do it, we will eventually do it.

“We would prefer that the FIA takes action not to encourage crazy investment like that.”

So as Renault waits for the governing body and Liberty together to try to impose limitations in budgets, engine dyno time and other simulation technology, the clock continues to tick. Those limitations may come in a few years’ time, but those plans seem to be forever being kicked into the long grass.

In the meantime, Renault may say it’s going to do F1 its own way – in an efficient way – but the timing beam doesn’t recognise how much money you’ve saved.

Mr Koskas has quite a task ahead of him.

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

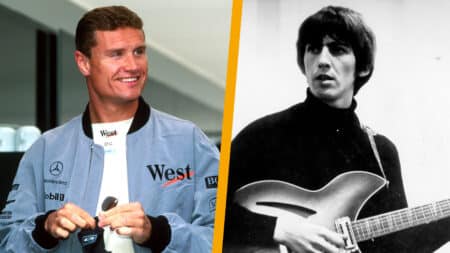

Former McLaren F1 team-mates Mika Häkkinen and David Coulthard are set to renew old rivalries in a new Evening with... tour – they told James Elson all about it

In Formula 1, driver contracts may look iron-clad on paper, but history shows that some of its biggest stars have made dramatic early exits

Former McLaren F1 ace told James Elson about his private audience with The Beatles' George Harrison, who played an unreleased grand prix-themed song