Nelson Piquet, Bernie Ecclestone, and BMW: Inside the Drama of the 1982 F1 Season

In 2009 BMW quit F1, its title ambitions in tatters. The same thing could have happened in the 1980s, but for an inspired Nelson Piquet and the stunning Brabham BT52

Taken from Motor Sport, November 2009

If you ask me, the blokes on the board at BMW lost their nerve. “We communicated our 2009 target four years ago,” said Mario Theissen in Valencia at the roll-out of this year’s car, barely seven months ago. “We set out a plan aiming at the first points in 2006, the first podium in 2007, to win in 2008, and we then stated that we want to fight for the championship from this year onwards. So far all targets have been met, so there is no reason to abandon the final and most important target. We want to fight for the title with the two big teams and whoever else is up there.”

From left: BMW Motorsport boss Paul Rosche, Bernie Ecclestone and Gordon Murray in the Hockenheim pits

Getty Images

Then, in July, the members of the BMW board were faced with having to sign up to the new Concorde Agreement. They looked at this year’s results (eight points from 10 races at that juncture), decided they had a good reason to abandon that cherished target, and shut off the money supply forthwith. Now we’ll never know if they made a timely decision or if they surrendered a golden opportunity to follow Renault as a mass-market car manufacturer capable of beating all those dedicated racing teams at their own game by designing, building and steering their own car to a world title.

To put things in perspective, it’s worth looking back at the similar potential disaster which Munich faced in 1982. It was an ugly scene. BMW’s racing boss was in open conflict with Bernie Ecclestone, owner of the company’s racing partner, Brabham, and Ecclestone’s sponsor was in dispute with the car company. In those days, however, drivers exerted more influence on team strategy than they would be allowed to do now, and it was only an open rebellion against Ecclestone by number one driver Nelson Piquet that resolved the rows. The reward for Piquet, BMW, Ecclestone and two groups of exceptionally talented technicians in Germany and England was the glorious drivers’ championship, which the Brazilian snatched out of the grasp of Alain Prost and Renault in the final race of the 1983 season.

Piquet in action at the European Grand Prix at Brands Hatch in 1983. This would be his third win aboard the BT52-BMW

Getty Images

Although BMW had become a consistent winning force in both touring car racing and Formula 2 throughout the ’70s, the company’s first F1 campaign was amazingly short-lived. It wasn’t until April 1980 that Munich officially announced it would be entering grand prix races, and although the first turbocharged BMW four-cylinder engine made its GP debut in the first race of the 1981 season, the whole programme was almost immediately put on hold while Piquet concentrated on winning the ’81 title using Cosworth-Ford power. The first victory with BMW came in June 1982 when Piquet won in Canada, but a series of irritating breakdowns meant that the second had to wait until March ’83, in Brazil. Although the Brazilian only won two more races that year, much-improved reliability and some close battling between all four drivers in the Renault and McLaren-TAG teams kept Piquet at the top of the points table and ultimately allowed him to steal the championship title.

“In the pitlane, our racing partner screamed at me like I was a little boy”

Right from the first appearance of Renault’s ‘yellow teapot’ in July 1977, Ecclestone and the mainly British teams which formed part of the constructors’ association (FOCA) had demonstrated their strong philosophical opposition to the French company’s exploitation of the rules which permitted ‘supercharged’ 1.5-litre engines. By the end of 1980, though, even Ecclestone had to concede that the future lay with the new turbo technology. When BMW approached him, he agreed on a technical collaboration that the German company hoped would result in a BMW-engined Brabham being ready to race in 1981.

Piquet already had good contacts with several of BMW’s personnel. He had contested two 1000km races at the Nürburgring in works BMW M1s, each time with Hans Stuck co-driving, and they had won outright in 1981, the year the race was stopped following the fatal accident that claimed the life of Swiss driver Herbert Müller.

As soon as the first turbo-powered F1 Brabham ‘hack’ chassis was available, Piquet was there to test it. The car ran regularly throughout 1981, with Piquet – who could see the engine’s extraordinary potential – ready to go testing at every opportunity. As BMW’s popular racing boss Dieter Stappert told me 10 years later, the BMW board of directors was becoming just as anxious as Piquet to get it back into action again. Meanwhile, Brabham’s sponsor, the Italian giant Parmalat, insisted on seeing results and demanded that Ecclestone should run at least one car with the ancient but reliable Cosworth V8.

“Bernie said it would be too difficult and complicated to run two different types of car at the same time,” Stappert explained, “so we decided to postpone our race debut until the first GP of 1982 at Kyalami. I could understand Bernie’s attitude, because I had already been in racing for a long time. But it was difficult to explain all this to the board of BMW and to the German public. Anyway, we got over that…”

The practical difficulties of making the BMW engine reliable were not so easy to surmount. “The first engines used a mechanical fuel injection system and the first time we tried the new [digital] Bosch Motronic engine management was at the end of 1981, in the pouring rain at Donington Park,” Stappert recalled. “That was a great test for us, because the Motronic worked perfectly. I remember Nelson coming in to the pits when it was so late in the day that all you could see on the car was the turbo glowing red on the left-hand side. He just said, ‘perfect, perfect, perfect.’

“Paul Rosche squeezed more and more power from the little four-cylinder stock-block”

“The Bosch people were there, of course, so we told them to carry on their development programme but first to make three copies of the box we’d used at Donington, because we knew it was working well. That way we could carry on the chassis testing. But somehow Bosch screwed it up. Although we didn’t find out until much later, apparently in measuring the box someone put several hundred volts through it and it blew up in a little cloud of smoke. And they couldn’t get it back together.

“That was bad enough, but what made it worse was that they wouldn’t tell us what had happened. They insisted it was the same, even when Nelson complained. We then went testing at Paul Ricard, one of the most difficult times in my life, because in two weeks we blew something like 17 engines. Nelson was doing all the turbo testing whenever there was a car for him to run, while Riccardo [Patrese] had the Cosworth-engined car. That Brabham handled beautifully, and every day it seemed Riccardo broke the lap record. I was amazed how Nelson stuck to the turbo test. You must remember that in 1982 he was the current world champion, but not once did he go to [Brabham designer] Gordon Murray and ask to be given the Cosworth car so that he could do five laps and beat Riccardo’s time. He couldn’t care less about Patrese’s lap records.”

Eyes on the prize: Piquet had trailed Renault’s Prost by as much as 14pts in 1983, but came back to steal the title

For the South African GP at Kyalami in January ’82, BMW played safe and took engines fitted with mechanical fuel injection pumps instead of the electronic system. The BMW board was demanding positive results from the big investment in F1, and the last thing they wanted to read about was the famous drivers’ strike which caused the cancellation of the first day of qualifying.

“A lot of people got upset with Nelson, because he was the driving force behind the strike with Niki Lauda,” said Stappert. “I didn’t know Nelson as well then as I would later, but I was sure there must have been a serious reason which at that moment I didn’t understand. I took all my courage in my hands and went up to Bernie and told him the same. Right there in the pitlane, our racing partner screamed at me as though I was a little boy. It made me feel so sick that I just turned around and left.”

After some more histrionics from Ecclestone, who at first refused to let Nelson practise on day two of qualifying, the new Brabham-BMW BT50 only just missed pole position. “The engine characteristics were still rudimentary,” confessed Stappert, “and although that car was very quick on the straight, you really needed someone brave to drive it. In the race, Nelson made a mess of the start. Trying to catch up, he missed the braking point at the end of the straight and slid straight on.”

Nelson and his German/Dutch girlfriend Sylvia Tamsma (in 1985 she gave birth to ‘young’ Nelson) spent a week with Stappert in Austria at the ski world championships on their return from Kyalami, and a lasting friendship was established. The genial but practical Stappert found a great ally in Piquet, who was as dedicated to making the BMW turbo a success as anyone in the engine shop. They both wanted to test and race the new car intensively, to speed up progress. But Ecclestone had a sponsor, Parmalat, to placate. He wanted BMW to withdraw the turbo in Argentina and Long Beach, the next two races, and cleverly he managed to outwit Stappert at a lunch he arranged with Hans-Erdmann Schönbeck, one of BMW’s board members, soon after the team returned from South Africa.

BMW’s Stappert was close to Piquet and then-girlfriend Sylvia Tamsma

Stappert: “Bernie issued a press release saying that the engine was too strong and Brabham needed to improve their brakes, etc. That was all bulls**t. We continued testing but we always had trouble with the electronic management. Then there was a test in April at Zolder. Bosch had four or five different boxes, and all five of them worked. Nelson would do five laps, everything was OK, then five more with another box.

“After the test in Zolder Nelson called Bernie from the little office in the pitlane. They were shouting at each other, apparently because Bernie wanted to discourage Nelson from running the turbo. But Nelson insisted that he wanted to use the turbo for racing, starting at the next GP, which would mean splitting the team by using different engines for each driver. He came out of the office and immediately told our engine chief Paul Rosche and me, ‘listen, I’m prepared to stick my neck out with Bernie, but I now rely on you to convince your BMW board to run only the one turbo car for me.’

“The funny sequel to this took place the day after I got back to Munich from the test, only a few minutes after I had persuaded Herr Schönbeck to agree to Nelson’s proposal. I was still in Schönbeck’s office when Bernie rang, and Schönbeck switched on the loudspeaker so I could hear what was being said. I couldn’t believe my ears as I listened to Bernie telling Schönbeck that he personally had managed to persuade Nelson to run just one engine.”

“Imagine, I nearly lost a championship because I lost my knob!”

With most of the leading teams in direct confrontation with the FIA president, garrulous Frenchman Jean-Marie Balestre, over car regulations (sound familiar?), off-track politics threatened to destroy the 1982 season. Piquet had won the Brazilian GP in March, driving a Cosworth-engined car, but was disqualified (in favour, yes, of a French Renault) when Murray’s ingenious but infamous water-cooled braking system was ruled illegal. Ten teams, predominantly British, then boycotted the first race of the European season. Although Piquet’s BMW-powered car made a low-key return (fifth place) at the Belgian GP, the patience of the BMW board was being stretched very thin.

At Detroit in June, the decision to run only one BMW-engined car seemed to have gone horribly wrong when Piquet failed to qualify. “That was partly our fault,” confessed Stappert, “because the engine stopped on the far side of the circuit, and by the time he got back to the pits qualifying was over. The next day it was pouring with rain… Gordon Murray was completely flattened. He couldn’t believe that one of his cars hadn’t qualified. He insisted that the only way to go was to stop racing the turbo and go back to intensive testing. I said, ‘No, Gordon, this is not possible. The board will not accept it. We have to race in Montréal in one week’s time.’”

After a series of threats and counter-bluffs, Murray agreed to Stappert’s pleadings. With the BMW sounding tremendous, Piquet went into the lead from René Arnoux’s Renault after eight laps. Stappert was on cloud nine. “For me, the world could have ended there and then: after the hard time we’d been given in Detroit, we had shown the people back home in Germany that we had a competitive combination.”

Piquet and Prost wheel-to-wheel at Zandvoort. The Brazilian would pip the Frenchman to the title by two points

Getty Images

Stappert got a big shock 10 laps from the end of the race when Ecclestone started to gather his things together in readiness to go to the airport for the evening flight home to London. Nelson was leading, but Patrese in the Ford car was not too far behind in second place. Stappert couldn’t believe that even Ecclestone would walk away from a race that his drivers were about to win in one-two order. “Feeling a bit helpless, I said, ‘but what do I do if Patrese catches Nelson and they start fighting for the lead?’ He just turned round and said, ‘Do what you like!’”

Inside the car, Piquet was in serious pain. “For that race the guys had done a lot of modifications, including an extra radiator in the nose of the car, which produced lots of heat which came straight back onto my feet. We should never have won – in fact it wasn’t BMW who won the race, it was me, because I did 72 laps with my feet completely burned.

“I didn’t stop because Patrese was behind me in the Ford car. I told myself there was no way I would stop, I’d done all the development on that car, no f***ing way was he going to win that one.”

Coming at a moment when BMW was ready to quit F1, the Canadian victory saved a situation which had seemed lost. The BMW board agreed to continue signing cheques and the Brabham crew breathed a sigh of relief. However, a string of mishaps and mechanical failures prevented Nelson from finishing six of the remaining eight races of the 1982 season. It wouldn’t be until ’83 that BMW could celebrate the world title.

Of his three titles, Nelson has always said that his 1983 success is the one which gave him the most satisfaction. “That was a fantastic period,” he remembers. “Wing cars with lots of downforce, turbo engines with 1500 horsepower, qualifying tyres good for maybe two laps… I loved it! If there are no escape areas, that makes perfection! We got paid a lot of money to drive those things in those conditions. It was the same for everybody. And good for me – that was my mentality about racing.”

There was also an incentive to beat Renault. With four races to go, and 36 points available, the manufacturer rashly plastered billboards across France with smug posters to congratulate Alain Prost, “our champion”. Granted, Alain had built up a 14-point advantage in the championship, but the adulation was to prove horribly premature…

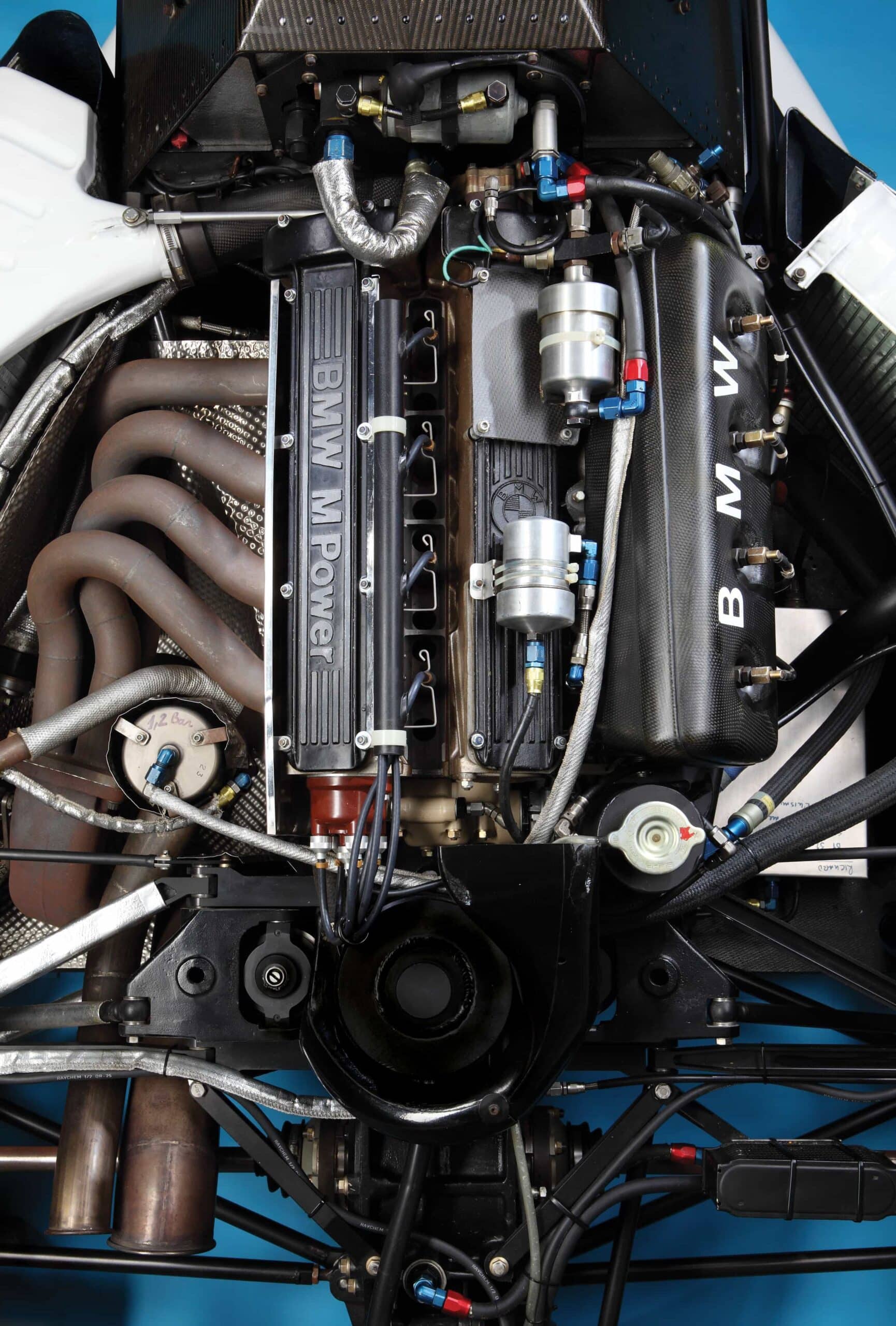

Piquet was to win only three GPs that year (against Prost’s four), but he had four other podium finishes and two fourth places. Murray’s Brabham BT52 was a completely new design to meet the emergency ‘flat bottom’ regulations imposed at the end of ’82. With its small fuel tanks, the BT52 was also able to take full advantage of the mid-race refuelling ploy that Murray had introduced in mid-82. Fearing the legal consequences that would surely follow a fire in the pits, Renault hesitated to adopt making fuel stops. By the time this policy had been reversed mid-season, the French had probably sacrificed the two or three points which would have been enough to defeat Brabham, BMW and Piquet. As Nelson himself says: “It wasn’t Prost who lost the championship, it was Renault who threw it away.”

Renault’s overcautious strategy would again cause it to miss out on the F1 title that had eluded the company for more than five years. With that 14-point cushion built up before Zandvoort, Renault’s technicians were given instructions to “freeze” the specification of their engine. BMW’s Paul Rosche pounced on this weakness to press on with his development programme, squeezing more and more power from the little four-cylinder stock-block.

Aided splendidly by team-mate Patrese, Nelson led all but three laps at Monza, where Prost’s turbo failed. In the European Grand Prix at Brands Hatch, he beat Prost hands down despite a scare during the pitstop when an air gun failed. Suddenly, Prost’s advantage had been cut from 14 points to two. The title would be decided in the final race at Kyalami.

Prost never looked more than second-best in South Africa. Renault’s technical equality with Brabham-BMW was gone, and he was resigned to defeat, even if he finished. When a turbo failure forced him to stop in the early laps, it was just a matter of Piquet bringing the Brabham home safely. Expecting that it might be necessary to out-psyche Renault, Murray had started both drivers on soft tyres and (of course) with light fuel. Nelson built up a 30-second lead in 28 laps before his stop: he first waved Patrese through, then the Alfa Romeo of de Cesaris. One or two hearts fluttered in the Brabham pit when his BMW seemed to be misfiring. In fact, he had cut back the boost to almost nothing as he cruised to the third place which would give him the title.

“I dropped back because I wanted to be sure of the championship,” Piquet recalled when I visited him at home in Brasilia in 2000. “There was this boost control inside the cockpit, and I backed off until there was probably just one bar boost. The engine was fine, but it was making a strange noise, which worried me. Then suddenly I found myself in fourth. I needed to be third, and the guy behind me [Derek Warwick in a Toleman-Hart] was catching me. But when I tried to turn up the boost, the knob fell off. For five or six laps I was trying to find this thing, accelerating to make it come back, or braking to make it go forward, before I could put it back on the dash. Imagine, I nearly lost a championship because I lost my knob!”

The first man to congratulate Piquet after his slowing-down lap was Prost. Ecclestone, as usual, was an early departure, looking amazingly disgruntled for someone whose driver was about to win the title for the second time in three years. In fact, he left instructions for Nelson to be admonished for letting de Cesaris through.

The new champion got back at his boss later on in the press room though, where he was thumping his knee in delight as he chatted with the waiting journalists. “I wanted to win [the championship] this year even more than I wanted it the first time,” he said. “In 1981 I won it for Ecclestone, for my family and for the people who had shown their faith by taking me into F1 straight from Formula 3. This time I won it for myself.

“We were a long way behind on points, so we said ‘OK, we’ll win the last three or four races and get the championship.’ We planned it all, we did it – and it was just fantastic. Every time Brabham gave me a chance to win the championship, I never let them down. I never lost the championship by a few points. And that makes me feel very good.”

There was a nasty postscript to come when rumours began to circulate that BMW had used fuel with illegal additives to boost its power in those crucial last four races. A sample taken from Piquet’s car in Kyalami was sent for analysis, and the eventual FISA report indicated that it did in fact meet all the requirements. Rosche insisted ever after that there had been no cheating, and he was justifiably upset to discover that part of the scrutineers’ sample had found its way into the hands of Elf, Renault’s fuel supplier.

The defeated challenger was in no doubt about the propriety of the win, though. In one of the tough statements that (along with a more personal indiscretion) would ultimately cost him his job at Renault, Alain Prost gallantly observed that, “the best car won the championship – and Nelson was the best man to drive it”.

Our thanks to Bernie Ecclestone and Robert Dean for their help with this feature.