Laura Ferrari: The driving force behind Enzo’s empire

A new film explores the relationship between Ferrari’s enigmatic founder Enzo and his wife Laura. Richard Williams reveals the true story behind their tumultuous marriage

1955 Shutterstock

Enzo Ferrari liked women. That’s a fact.

Ask Gerhard Berger when he was happiest in his career as a racing driver and he’ll talk about 1987, his first year at Ferrari, when the car was quick and after a race the Old Man would take him to lunch at the Cavallino, across the road from the factory, and ask him about the girls he’d had that weekend. When Enzo died the following year, aged 90, joining his father, mother, wife and first son in the family tomb, he left two mistresses along with a second son.

Perhaps the best thing about Michael Mann’s Ferrari, particularly for those who can ignore the fast-and-loose treatment of certain historical facts and don’t care that the film’s depiction of the Mille Miglia – where the story reaches its climax – makes the mighty sports car classic look more like the final of the Formula Ford Festival, is the attention it pays to the women. That aspect, rather than the portrayal of the racing world of 1957, the year in which the action is concentrated, is where it justifies its existence as a Hollywood drama and might even have something interesting to offer.

Michael Mann’s Ferrari focuses on a few tumultuous months in 1957

Eros Hoagland

Three of the most important women in Ferrari’s life are given due prominence. The great Spanish actress Penélope Cruz dials down her natural beauty to play Laura, Enzo’s wife, as a figure bruised and vengeful after 30 years of a turbulent marriage: “She was a different creature then,” her husband says, reflecting on their early days together, “but so was I.” His mother, Adalgisa, is played by the veteran Italian actress Daniela Piperno as a caricature of the eternally suspicious and critical mamma. Most impressive is the American actress Shailene Woodley, who quietly brings life, depth and vigour to the role of Lina Lardi, the long-term mistress, a figure previously condemned to a shadowy existence in accounts of Enzo’s life.

It’s unlikely that Laura ever fired a pistol in the general direction of her husband, as the film suggests, or that Enzo (played by Adam Driver with great presence but none of the man’s private ribaldry) ever gave her a half-share of the company and then had to bribe her to get it back. Michael Mann and his screenwriter, Troy Kennedy Martin, based their narrative on Brock Yates’s 1991 biography Ferrari: The Man and the Machine, in which fact and speculation are scrupulously separated. But in their search for what creative people call emotional truth, their film sometimes privileges drama over actual history.

In real life, Ferrari’s first encounter with his wife-to-be took place on a side street near Turin’s Porta Nuova train station one evening shortly after the end of the Great War. He was aged 20 and working for a company that converted wartime trucks into cars for road use, delivering each rolling chassis to a coachbuilder in Milan. Laura Garello was a couple of years younger than Ferrari, working as a dancer, and she struck a young man away from home and in need of female company as “beautiful, blonde, elegant, petite, and with lovely eyes”.

Enzo Ferrari’s wife Laura is played by Penélope Cruz

LANDMARK MEDIA / Alamy Stock Photo

More than one Ferrari historian has wondered what had led these two to those insalubrious Turin streets that night in 1921, questioning in particular the true nature of Laura’s occupation.

By the time Enzo’s ambitions started to become reality, they were a couple, sharing his apartment in Modena while he divided his working hours between establishing a bodybuilding company of his own and driving in races for the works Alfa Romeo team. They would not be married until 1923, but a private collection of letters and other documents, to which Motor Sport has been granted access, shows that long before their wedding he was addressing the envelopes containing his letters to her, whenever she went off to spend time with her sister or took a break by the sea in Rimini, as to “Laura Ferrari”. It was the start of a partnership that would see her play a significant and eventually controversial role in the company’s history, and that was played out against a background of quarrels and estrangements.

When, after 40 years of marriage, Enzo presented his wife with a first edition of his autobiography, the message he wrote on the title page of Le Mie Gioie Terribili (My Terrible Joys) in 1962 was not what might have been expected. There was no “To my darling wife”, “To dearest Laura” or “To the woman who has been by my side through thick and thin”. Or even “To Bibi”, which had been his pet name for her. Instead, in his flowing script and his favourite violet ink, he dedicated her copy “To the mother of Dino.” After four decades together, that was how he saw her, as the woman who had given him the precious son whose death from muscular dystrophy at the age of 24 had left a wound in his heart that refused to heal.

Enzo and Laura on their wedding day in 1923, two years after first meeting at Turin’s train station

Motor Sport

“Ferrari’s mother stayed away from the marriage ceremony and the service that followed it”

As man and wife, they could both be difficult people. Enzo, gregarious in nature – at least with his close circle of friends – and gifted as an organiser of men, could be tricky and manipulative. As the years went by he grew more and more reluctant to leave Modena, where he continued to live, or nearby Maranello, where he built his factory. Not even the sight of his cars competing in Europe’s greatest races could drag him to Monaco, the Nürburgring or Le Mans. His seeming reclusiveness and the habitual wearing of dark glasses contributed to an aura of mystery that worked to the commercial advantage of the man who would become known as the ‘Pope of the North’ – albeit a pope without a vow of celibacy.

Some historical facts have been blurred in Mann’s films but the cars themselves have been painstakingly built for racing accuracy

Eros Hoagland

Laura, however, had no such scruples about facing the outside world. She travelled as she had done during the days of their courtship, which took place against the background noise of disapproval from both sides: from his recently widowed mother and from the Garello family, who were not initially enthused by the idea of their daughter marrying a young racing driver with an uncertain future. She travelled not just to the racing events but, as her surviving correspondence with Enzo demonstrates, to resorts where she could rest and recover from bouts of depression induced by emotional stress.

During the weeks, stretching to months, that she spent at a hotel in the fashionable town of Santa Margherita Ligure on the Italian Riviera in the winter of 1921-22, Enzo wrote long letters in which he addressed her as “Cara Laura” or “Laura carissima”. Some of the letters contained money; in one he enclosed a press cutting in which his company, Carrozzeria Emilia, was praised for the elegance of the bodywork it had exhibited on an Alfa Romeo chassis at the Milan motor show.

Whereas Enzo kept away from the track, Laura would often be present – here at the 1960 Portuguese Grand Prix

Getty Images

Alas, such optimism was misplaced, at least in the short term. By the time she returned to Modena in the spring, the little company was in trouble and in the early stages of liquidation. As it closed its doors, Enzo needed his mother’s help to meet his debts. Laura retreated to Sestola, 3000ft up in the Emilian hills, for clean air and further rest while he recovered from his business reverse by deepening his links with Alfa Romeo. After she had returned from another winter stay on the Riviera, they were married in Turin on April 28, 1923. His mother stayed away from the civil ceremony and the religious service that followed it, where the congregation consisted of the bride’s family and friends.

Although Enzo was still racing regularly, more of his time was now taken up by his involvement in the running of the racing team, to which he helped recruit the engineers Luigi Bazzi and Vittorio Jano from Fiat, both of whom would play significant roles in his own future endeavours. Laura continued to suffer from her problems, spending her first winter as a married woman back in the hotel on the Riviera while Enzo was in Geneva, helping the company’s Swiss agent with the development of a potentially important market.

Laura, far right, at the 1960 British Grand Prix, handing a prize to Tony Brooks, second from left

Getty Images

Laura’s jealousy, aroused by the way other young women tended to gather round racing drivers, soon became a source of friction in a relationship that was already losing the warmth of its early days. Occasionally she came to a race: she was with him early in 1924 when he beat Tazio Nuvolari in the Circuit of Rovigo. More often she was either in the hills, at the seaside or with her family in Turin, on the pretext of needing rest.

Enzo’s letters acquired an accusatory tone. “Laura…” was how some of them began – no “Cara” or “Carissima”, never mind “Bibi” – including the one in which he delivered an ultimatum that seemed to persuade her to return to his side, at least in body if not always in spirit. He still raced, but less frequently, his thoughts increasingly devoted to the creation of his own team, with the aid of a few wealthy backers and the income from a group of carefully selected trade sponsors, and a headquarters in Modena’s Viale Ciro Menotti, on the corner of the Via Emilia.

Door-to-door jostling in Mann’s recreation of the 1957 Mille Miglia.

Eros Hoagland

“There was a showdown in which they discussed a separation”

When the newly launched Scuderia Ferrari celebrated its very first win, in the Trieste-Opicina hillclimb in 1930, Laura was there. For the victory photograph, the team boss’s wife stood smiling alongside Nuvolari’s winning Alfa P2, with her proud husband on the other side. But at the end of a debut season in which the team won nine of the 22 races it entered, there was another domestic showdown in which they discussed a separation before deciding to try and patch things up. Although she began to take a greater interest in the workings of the new team, with specific concern for its expenditure, she was still spending much of her time, after the death of her parents, with her sister in Turin.

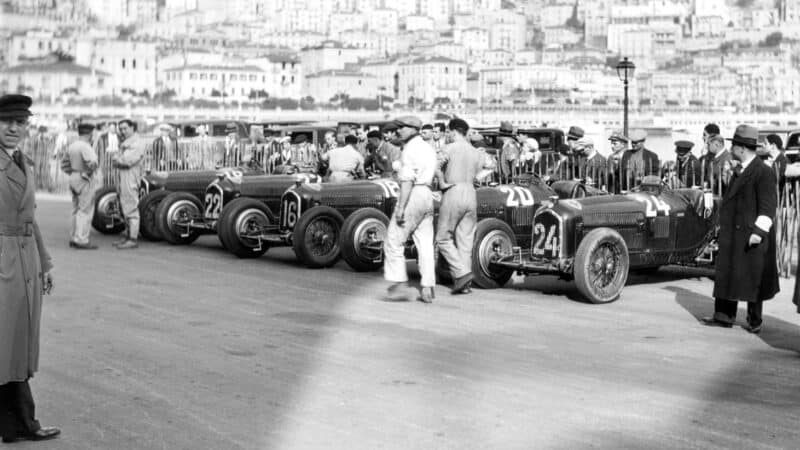

Enzo’s mother now lived on the Corso Canalgrande in Modena, only a few hundred yards away from the Scuderia, but her relationship with her daughter-in-law was never cordial. Her son, however, had other things on his mind. Alfa Romeo’s management had decided to close their racing department and transfer the running of their works team to the Scuderia Ferrari for 1934, with Achille Varzi, Louis Chiron and the Algerian prodigy Guy Moll as their drivers. Ferrari travelled to the opening race of the season, in Monaco, where Moll, at the wheel of one of the previous year’s P3s, took a brilliant victory. A week later Varzi won the Mille Miglia. Moll, alas, would be killed later in the season in the Coppa Acerbo.

Scuderia Ferrari Alfa Romeos at the 1934 Monaco Grand Prix

Getty Images

By now he had encountered a second young woman who would play a major role in his life. Lina Lardi degli Aleardi, the 19-year-old daughter of a Modenese family, was working as a secretary at Carrozzeria Orlandi, where Enzo sometimes ordered bodywork for his Alfas. Soon she was transferring her skills to Ferrari’s offices and accompanying him on business trips to Milan. After initial opposition, her family came to accept her role as the mistress of a man who was clearly making something substantial of his career.

The Scuderia’s first win – the 1930 Trieste-Opicina hillclimb

Motor Sport

Enzo had given up hope of becoming a father when Laura told him, 12 years after their first meeting and eight years since their wedding, that she was pregnant. A few weeks later, after finishing second to Nuvolari in the Circuito di Tre Provinci, he finally called a halt to his career as a driver. Their son was born in January 1932 and named Alfredo (informally shortened to Dino) after his father and his older brother, who had both died of pneumonia in 1916, 11 months apart. Soon after Dino’s birth, the family moved into an apartment above the Scuderia’s garage and workshops, on the street whose name would soon by changed to Viale Trento e Trieste, and from where Enzo, now Alfa Romeo’s official agent in Emilia, Romagna and the Marche, would receive his wealthy customers.

For the next few years Laura’s priority was Dino, who would grow up in a spacious apartment in a building on Largo Garibaldi, close to the Scuderia. Enzo set up his mistress in a pleasant detached house with a garden in Castelvetro di Modena, a small medieval town three miles from Maranello, making it a convenient stop on his drive home from the factory. His visits to Lina became almost as much a part of his daily routine as the post-breakfast visit to his barber and friend, Antonio D’Elia, on the Corso Canalgrande.

Much of the filming took place around Brescia in October 2022

Eros Hoagland

Dino was aged 13 when Lina Lardi gave birth to his half-brother, Piero, in 1945. The elder boy showed promise at school and college before joining his father to work as a designer, but from childhood he had shown worrying symptoms that were eventually diagnosed as muscular dystrophy, progressively robbing him of his strength as he grew to adulthood.

After his death in 1956, his father’s routine for starting the day was extended to incorporate a trip to the family tomb in the cemetery of San Cataldo. The tragedy widened the already considerable rift between Laura and Enzo, exacerbated by the knowledge that the particular strain of MS, known as Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy, or DMD, which at first enfeebled and then killed their precious son, was a genetic inheritance passed on via one of the mother’s chromosomes.

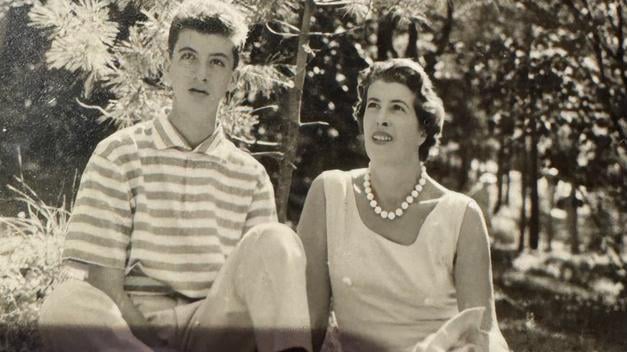

Enzo’s other family – son Piero and mistress Lina Lardi

Klemantaski Collection

Deprived of her son, Laura’s concern for the company’s finances became more evident as she freely criticised expenditure that she considered unnecessary, often joining the team at the race meetings to keep tabs on their activities.

The resentment created by her increasingly frequent interference was destined to explode at the end of the 1961 season – one in which, ironically enough, the Scuderia’s Formula 1 cars had triumphed in the F1 world drivers’ and constructors’ championships while their sports cars had won the Sebring 12 Hours, the Targa Florio and the Le Mans 24 Hours.

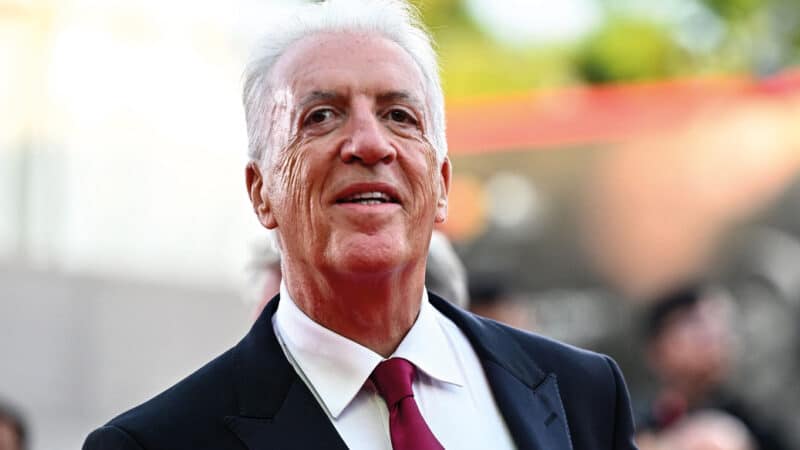

Piero, now in his late seventies, is vice-chairman of Ferrari

Getty Images

Via a lawyer, eight senior managers wrote to Enzo to complain about her behaviour. An enraged Ferrari responded by firing them all. They included Romolo Tavoni, the team manager, Carlo Chiti, the chief designer, and Giotto Bizzarrini, the head of experimental engineering. The result of this upheaval was a far less successful 1962 season, although the surprise promotion of the young engineer Mauro Forghieri to replace Chiti would eventually earn a handsome dividend.

“Enzo implored Fiamma, in dozens of letters and countless phone calls, to marry him”

For Enzo, the house in Castelvetro would provide a haven of calm. Michael Mann’s film carries Piero Ferrari’s endorsement, seeming to guarantee a kind portrayal of his mother, but we already knew that, by comparison with Laura, Lina offered a more emollient and much less-demanding temperament – something she passed on to her son, who inherited his father’s eyes but not his ruthlessness in business. In a touching performance, Shailene Woodley uses Troy Kennedy Martin’s script to put flesh on the bones of Lina’s character, giving her a gentle resilience to match her sweeter nature and helping to explain to those outside the family how Ferrari might have managed to maintain both households for so long.

Lunch before the 1956 Syracuse Grand Prix, from left: Luigi Musso, his girlfriend Fiamma Breschi, Louis Klemantaski, Peter Collins and Motor Sport’s much-travelled scribe Denis Jenkinson

Getty Images

Laura died in 1978, after a long illness and 55 years of marriage. The film relies for much of its narrative tension on the claim that, in the early days, Enzo had given his wife half of the company’s shares. He asks for them back when he begins negotiations for a merger with Fiat in 1957, prompting her to demand a cheque for half a million dollars in recompense, along with a promise that Piero would not be allowed to use the Ferrari name until after her death.

The half-share is a complete fiction, and the negotiations with Fiat (and also Ford) did not begin until 1963, although Fiat’s Vittorio Valletta had assured Enzo, during a crisis in 1956, that if things got really bad, the Turin giant would always be there to help. The promise was real enough, however, ensuring that Piero Lardi did not become Piero Ferrari until he was 32 years old, at which point he and his mother went to live with Enzo in the house on the Largo Garibaldi once occupied by Laura and Dino.

Long before the deaths of Laura and Lina (in 2006), Ferrari had become obsessed with another woman, whose story lies just outside the film’s time-frame. In 1958 another of his drivers, Luigi Musso, was killed in the French GP, leaving behind the beautiful young actress, Fiamma Breschi, for whom the Roman ace had left his wife and children. Enzo comforted her to the extent of setting her up with shops first in Bologna and then in Florence and eventually imploring her, in dozens of letters and countless phone calls, to marry him, despite a 35-year age gap. “According to his letters,” Breschi said before her death in 2015, “I was the first woman in his life.”