Hans Stuck: The Motor Sport interview

An endurance racing specialist with two Le Mans victories to his credit, plus 74 grand prix starts during a battling Formula 1 career. Hans Stuck's story is as endearing as he is.

Getty Images

Hans Joachim Stuck Junior had a hard act to follow. His father had famously raced for the mighty Auto Union team in the 1930s and been hailed in his native Germany as the king of the long mountain hillclimbs. Hans Junior inherited the passion for racing as a child, watching, learning from his father, and having his first taste of a race track at the Nürburgring where his father taught at the racing school. He won his first 24-hour race there when he was just 19 years old, quickly forging a reputation as one of the sport’s best long-distance drivers with BMW and Porsche, winning Le Mans twice for Porsche in 1986 and ’87. He always preferred closed cars but achieved his dream of F1, racing for March, Brabham, Shadow and ATS in the 1970s. Hans raced for almost 50 years before retiring to take up his position with Volkswagen testing and refining both competition and road cars, a role that he continues to this day. He looks back on a long and varied career.

Motor Sport: We know a lot about your father’s success but what was he like as a man? How did he influence your early years?

HS: He was an outstanding person. As a child I went with him to races and hillclimbs and saw the respect, the admiration of his talent. Even today people say he was a real gentleman, friendly to everyone, and he told me ‘Little boy, if you are friendly then everyone will be friendly to you too’. My mum was the tough one, but on the race track my dad knew what he had to do, a great competitor. He was a great example to me, I have tried to live up to him in my life.

Those guys were so brave; when I drive the Auto Union I cannot imagine how they did a race of 300 kilometres round the Nürburgring at over 200mph. They were not only brave, no seat belts, no proper helmet, a bad seating position so close to the steering wheel, it was also physically demanding. When you drive those cars you are sitting so far up front it’s really difficult to feel what the car is doing, especially with all that power and skinny tyres. I can only raise my hat to him and all those drivers.

Hans Stuck Snr drove for Auto Union prior to World War II. Here he is in action at AVUS in 1934

What did you learn about driving, and racing from such an illustrious father?

HS: Not so much, really, but at the start of my career I was famous for going sideways and he told me ‘don’t go so much sideways, be more careful with the tyres’. I said ‘But Daddy, I love it…’ so I don’t think it helped. People say he must have been a hard act to follow but it was never like that for me, I only had positive energy, he was such a nice guy. There were expectations, of course; my success was not as much as he had, but it wasn’t bad, so that’s ok with me. I tell you, I have one record: he was married three times, I am four times, so I win that one! My time in racing was when sex was safe and racing was dangerous.

Let’s talk about two tracks where you’ve had success, the Nürburgring and Spa-Francorchamps, both great tests of a driver.

HS: Both are very special but the Nürburgring is the most demanding, the track is always changing; after the winter there are more bumps, the surface never stays the same. Also, there are no run-offs, nowhere to go if you lose control. I first drove there when I was nine years old. My dad was a teacher at the racing school, and he told me ‘never, ever lose respect for this track. If you do, it will bite you.’ I thought of that every time I raced on the Nordschleife which is the most demanding of any circuit in the world. Spa is maybe one level below, you know, but there were plenty of things to hit – I mean, there was a house by the track at Stavelot. In my dad’s day, and in mine, we didn’t know any better, but that’s how it was, part of being a racing driver. Even now things can go wrong; you can be hurt, even on the modern tracks. The perfect lap of Spa is wonderful, it’s so fast, and it flows, but when it’s wet it’s very demanding, it sorts the men from the boys. There was a river across the track at Eau Rouge when it rained and even now that corner is demanding in a quick car.

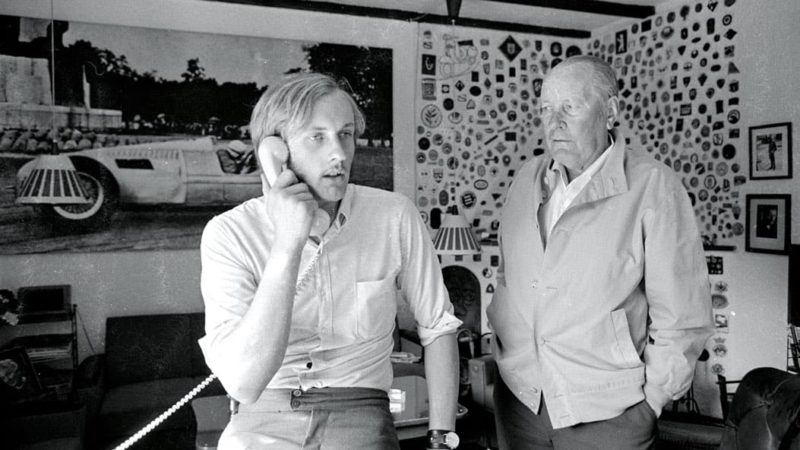

Hans Stuck Jnr takes a phone call overseen by his father at their family home

Alamy

We should talk about the BMW 3.0 CSL. You raced it with great success, and it’s still a great-looking racing car.

HS: Yes, I did a lot of the development at the Nürburgring with Jochen Neerpasch. We put this big wing on the back, a spoiler at the front, some aero on the roof, and with these there was so much downforce. I went 21 seconds quicker – can you believe that? It was incredible. Then we added the ABS braking, and we went faster, another few seconds.

“I had some great team-mates, like Peterson, Amon, Ickx…“

This was the time when we realised the importance of the aero, the downforce. At BMW I had some great team-mates, like Ronnie Peterson, Chris Amon, Jacky Ickx; this was fantastic for me, gave me the chance to learn from them, get closer to the limit. As a young guy there was always something to learn from them. My partnership with Ronnie taught me a lot about my racing, the way I approached it, the way I drove. He would go flat out from the word go in practice, discover the limit, feel what needed doing, and then he’d come back and start moaning about the car. Normally you’d go out, build up slowly, check it out and then build the speed. I will say, however, Ronnie and I never finished a race when we shared the BMW because we were always trying to show that one of us was faster than the other. At Brands Hatch, with the 2002 turbo, I crashed the car 25 minutes into the race, put the car over the guardrail. It was destroyed, so I walked back to the pits, Ronnie and I packed our bags and headed for home. The next morning, in Munich, I got a call from Jochen Neerpasch’s secretary at BMW, she says ‘Mr Stuck can you please come to the office, Mr Neerpasch wants to see you asap.’

When I arrived Neerpasch is sitting behind his big desk in a bad mood. He looks at me, says ‘OK, you had this crash but, when you left, the race was stopped for another accident. We got your car back, there wasn’t that much damage, but we didn’t have any drivers any more.’ This was not good. He said he couldn’t fire us but we’d have to pay a 10,000 deutschmarks penalty and we wouldn’t be reimbursed for our travelling costs. I can laugh about this now.

The mighty BMW 3.0 CSL. Stuck was key in honing what was perhaps the ultimate touring car of the 1970s

mcklein

You are 6ft 4in, so what was it like when you went to Formula 2 single-seaters in the 1970s, which suited smaller drivers?

HS: Well, there wasn’t much I was able to do about that… but through my career I always preferred the closed cars, to race with a roof over my head. My head was always sticking up in the air, in the F2 cars, and my team-mate Patrick Depailler was always faster at the end of the straights because my head was in the wind. The March, with the BMW engine from Paul Rosche, was the best car at that time so I was able to get some good results. In F1 it was the same problem, the buffeting on my head, so I was always more comfortable with a roof.

Your performance in F2 took you to F1 in 1974 with March. Was this what you had always been aiming for?

HS: Yes. It was fantastic for me despite being so tall for those cars. Max Mosley came to see me and my dad at the end of ’73 and asked me to do F1 with the March 741. The first race was in Argentina; I’d never seen the circuit before, never driven the car before, but Carlos Reutemann took me round in his road car, gave me a lot of good advice. The March was not so competitive but I scored some points in my first year and it was a dream to be suddenly part of this F1 club. I enjoyed every day, every race in these cars with the big, fat rear tyres, and limited aerodynamics; you could slipstream, you could overtake. I think we had the best of times in those days.

A tale of two F1 teams: Stuck raced for March in 1976 scoring a best of fourth in both Brazil and Monaco

Getty Images

Stuck impressed in Formula 2, despite being rather lanky for the cars. He took three wins on his way to second in the 1974 season in the March-BMW

Mcklein

You drove for both Max Mosley and Bernie Ecclestone in the 1970s. What was Bernie like to work for at Brabham?

HS: First I must tell you how it started with Bernie. I didn’t have a contract for 1977 but Carlos Pace had been killed in a plane accident. I got a call from Bernie, he says ‘Hey Hans, if you want to drive for me, come and see me’. I flew to England, talked with him in his office, and he asked me what I wanted to earn for the season. The year before, with Max, I got $100,000 and I needed this to look after my elderly parents, so I told him that’s what I decided. Just at that moment his phone rang and he starts talking Italian to a guy called Arturo, tells him he’ll call back. ‘That was Merzario,’ says Bernie. ‘He says he’ll race for me for 30,000; that’s what I’ll offer you, so do you want the deal or not?’ Well, not what I wanted, but I told him I’d agree if there was extra money for every championship point. He said OK, and we signed the contract. My first race was at Long Beach. I was quicker than John Watson in practice, and that evening we went out for dinner. ‘Hans,’ he said, ‘this is the start of a good partnership and friendship but I have to tell you that the call I received when you came to sign the contract, that wasn’t Arturo Merzario, it was my secretary next door…’

“That was Merzario. He’ll race for me for 30,000… deal or no deal?“

The race was wet, lots of spray, but I started on the front row, alongside James Hunt, and was into the lead on lap 14 when I slid into the wall. The clutch cable had broken and I was thinking about how I’d get away from a pit stop without a clutch when I just lost the car under braking. I had two podiums and 12 points that year, which was not so bad. Bernie and I are still good friends, and if I ever have any kind of problem he is there to help me. Immediately. People may not know this but when you do a good job, and you have him as a friend, he’s always there for you. That’s really cool about Bernie.

Better would come with Brabham in 1977 (below) where he would take his two podium finishes

In 1979 you finished your F1 career with ATS. Do you regret going there after working with bigger teams like Brabham and Shadow?

HS: I had an offer from Frank Williams for ’79 but that was in his second car and meant pre-qualifying in Europe, and the money wasn’t good. So, when Günther Schmid offered me good money in a single-car team I decided to take it. Soon I realised this was the wrong decision; the car wasn’t so good, there was not the best atmosphere in the team, and Schmid was always interfering, always angry about something. When we got to Monaco all of a sudden we had ATS wheels on the car – well, maybe he made good wheels for road cars but had he had these wheels tested on an F1 car? He dismissed this, you know, telling me to shut up, saying the wheels are good. In the race I was running well, up into eighth place ahead of the Brabhams when I turned into the harbour chicane on lap 30 and the front left wheel broke. It flew off the car, bounced off a lamp post, and into the water next to the boat where Schmid was watching the race with all his guests. He freaked out, but this was the kind of thing that happened. I don’t regret joining the team, there were good times and bad times, it just wasn’t one of my best seasons.

Hans Stuck with Günther Schmid of ATS, which didn’t work out well

Getty Images

Your finest results came in endurance races, including two wins at Le Mans. Which did you prefer, La Sarthe or Daytona, both good hunting grounds for you?

HS: That’s easy. Le Mans. It’s such a fantastic race, especially when there were no chicanes on the Mulsanne Straight. When you have a good car, a good team, like with Porsche, then it’s the perfect race. Daytona is definitely the more demanding track, much harder on the cars, and the drivers. I always had this dream to win at Le Mans and the first time, in ’86 with Derek Bell and Al Holbert in the Rothmans Porsche 962C, we won by eight laps. On the podium it was amazing, surrounded by thousands of people. It was a big step in my career.

“In the 962 I could take one hand off the wheel on the Mulsanne“

We won again the year after, same three drivers in the 962, and this time by 20 laps. It’s just fantastic to win this race once, never mind twice in two years. Our race director Peter Falk told us ‘to finish first here, first you have to finish’ and that is the key at Le Mans. There are so many things to consider – the weather, all the other cars on the track, the reliability, the engine, the brakes, the gearbox. Now it’s flat out all the way but in our day we were maybe at 80 per cent, taking care of the car, keeping away from the kerbs, and this is very demanding for 24 hours. Porsche was absolutely the best team I ever raced for, and looking back over 50 years this was definitely the best time for me and the family are friends to this day. I learnt so much from working with them, the attention to detail, the way they built the cars, how to drive the best possible long-distance race. For a driver, the car has to be just right, relaxing to drive. I mean with the 962 it was so stable you could take one hand off the wheel on the Mulsanne. I drove other cars which would pull left or right, and so you cannot relax.

The perfect race: when Stuck joined Porsche and was paired with Derek Bell and Al Holbert in the 962C, they were unstoppable at Le Mans in 1986 and ’87

Getty Images

What was it about the Porsche 962 that made it such a successful racing car?

HS: It was a combination of downforce, power and drivability. I did thousands of kilometres testing at Weissach in the 956 and the 962, driving from dawn to dusk day after day, and that meant I really felt a part of those cars. This was a lottery win for me because no two cars were the same, they were hand-built, but I was able to feel exactly what each car was doing and to spend so many days in the cars gave me an advantage. Of course I was first and foremost a racer but I enjoyed the development work which I knew would pay dividends. Some days I would be in the car for six or seven hours, and that kind of endurance testing was part of what made Porsche so successful.

Stuck’s 962C wins at La Sarthe in 1987. The car had a great blend of power, aero and drivability, according to him.

Getty Images

Moving forward to the end of your career you raced in DTM at a time when the cars were very technical, a quantum leap from what you’d driven before.

HS: Yes, and I’d never driven a four-wheel-drive car when I joined Audi with the Quattro. Dr Piech had told me they were going to do DTM in 1990, up against the BMW M3 and the Mercedes 190, I was amazed, surprised, but he said ‘Mr Stuck, keep quiet, you wait and see’ and of course the car was fantastic with the power of the V8 and the all-wheel drive. I had a lot of help from Walter Röhrl, who’d developed and driven these cars in the World Rally Championship and he gave good advice about the torque split, percentages, how much grip to the front, how much to the rear, and using the limited-slip differential.

In terms of touring cars in 1994 the Opel Calibra was the maximum – Cosworth power, automatic gearbox, weight distribution movable to the front or back for braking and accelerating. The automatic gearbox was something new for me – I mean when I was at Brabham we had a seven-speed manual gearbox and I worked out that, for the Monaco Grand Prix, I would be changing gear 1065 times.

This meant driving with one hand a lot of the time. A totally different world to what I found in the 1990s.

Crossing over from Porsche to Audi for the 1991 DTM with the Quattro. Stuck would win four times that year

We should remember the Procar series that supported grands prix in 1979 and ’80 with the BMW M1 because you had done a lot of development on that car.

HS: It was fantastic to have the F1 drivers in these cars. I loved it, they were quick, the prize money was good. It was more of a challenge for the current F1 drivers who, unlike the privateers, had never driven these cars. I did a lot of the testing before the M1 was homologated. To get the car road legal we had to do 20,000 kilometres within a couple of weeks so BMW called all the drivers to Munich and gave us a 300 kilometre route around the area. We did this in shifts, starting at 7am, and going through country villages where the farmers would stand on the road waving their arms, shouting that we should slow down. We went fast to cover the mileage and because it was more fun for us. Once these shifts were done we took the car to the track to get it prepared for racing.

The BMW M1 Procar series that supported F1 for two seasons. Chaos reigns at Brands in 1980

DPPI

Finally, what’s your view of F1 today? Do you take an interest along with your job for the Volkswagen Group?

HS: I think F1 could do more for our environment. They could do things like use synthetic fuels for example, and I’d like to see more teams going into it with an actual chance to win. F1 is still the best, the pinnacle of the sport, but I really don’t like things like the DRS and if we had less aerodynamics, less downforce, there could be a big cost saving and better competition for everybody.

I am excited that Audi is going to join the grid in 2026, and partnering with Sauber is the right way to do this. It won’t be easy for Audi by any means, but they will bring innovation, as they have many times before in other areas of racing, and in time I’m sure they will be successful.