Page 29

Matters of Moment, March 1979

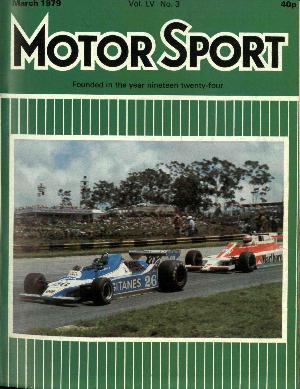

• The pride of France It is too early to say whether the Ligier JS11s that have won convincingly the…

• The pride of France It is too early to say whether the Ligier JS11s that have won convincingly the…

Had I gone to Formula One races in South America instead of keeping my sense of proportion by staying in…

Drophead XJ 2-door produced Lynx Motor Co. of Station Road, Northiam, near Rye, in Sussex are offering to convert the…

A section devoted to old-car matters A Distinguished Chummy Austin Last September we a note a reader who had to…

Howey's Accident Sir, I read as always with interest your comment on Dr. Brian Hamilton's letter reference Dick (R. B.)…

The Historic Commercial Vehicle Club has announced the date of this year's London-Brighton Commercial Vehicle Run as May 6th. Its…

Leo Villa One of the most famous of all the racing mechanics of the old school has died in hospital,…

Those who read the piece last month headed "100 m.p.h. From 750 c.c." may have realised that we made rather…

Back in 1935, when private flying was a more carefree affair than it now is, two pilots from the Cotswold…

Last November the Lancia Stratos was said to be making its final official appearance in rallying, and indeed when the…

There are some interesting references to cars in "The Unforgiving Minute" (W. H. Allen, 1978), the fascinating if at times…

The Ziebart Vehicle Rustproofing concern has introduced new services for car users. One is their Envirogarde laminated windscreen-repair service. This…

"Automobile Year 1978/79" Edited by Douglas Armstrong. 249 pp. 12½" x 9½" (Patrick Stephens Ltd., Bar Hill, Cambridge, CB3 8EL.…

The Jaguar Drivers' Club 20th Annual Historic Race Meeting will be run at Silverstone on March 10th. Races include rounds…

One of Louis Coatalen's great interests was motor racing and when he became Chief Engineer of the STD organisation he…

With their customary capability the VSCC use Brooklands for their post-Christmas driving tests, a convenient and historic venue, even if…

The 1979 Monte Carlo Rallye will certainly go down in history as a dramatic motoring event, but away from Darniche's…

In which the Deputy Editor reviews his 1978 motoring activities Some loose reflections on my activities in 1978, preparatory to…

While these words are being read in the March issue of Motor Sport the South African GP will be in…

A dependable electric torch is an essential part of the car-user's equipment, especially during the dark days of winter (you…

Jenson Button expands racing portfolio with off-road debut as he races in 2019 Mint 400 and Baja 1000 The 2009 Formula 1 champion Jenson Button will race in the Baja…

Guenther Steiner left Haas after a last-place finish in the 2023 F1 championship with little sign of progress. But the team boss may not have been to blame, says Mark Hughes, with his departure more significant than just a personnel change

The Covid-19 crisis has already taken a terrible toll on the world and last weekend, at the Spanish Grand Prix in Jerez, it was MotoGP’s turn to suffer. A fortnight…

Fred Vasseur's first year as Ferrari's team principal wasn't flawless but it showed signs of promise. The Frenchman sat down with Chris Medland to discuss the pressures of Maranello and what 2024 may hold in store