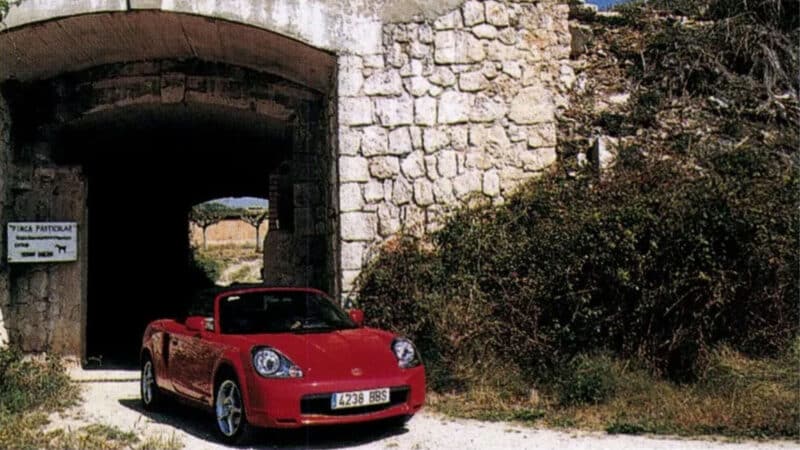

Spain had big plans in the early 1920s. Part of the grandiose scheme was the construction of a modem road network. To this end, a Portland Cement factory was built close to Sitges. The track was their sampler, proof of the worth of their pre-cast sections, of the silence and comfort afforded by their aforesaid angled joints which precluded jarring caused by both wheels of an axle crossing them simultaneously.

This two-kilometre (1.242-mile) cutting-edge construction was gouged out of a rock face and moulded from 3.5 million kilograms of concrete in the space of 300 days during 1923. Two thrusting young architects, Jaume Mestres i Fossas (track) and Josep Maria Martino Arroyo (pits and grandstand), oversaw the project, and part of their brief was to build a Royal Box: King Alfonso XIII was coming to the races.

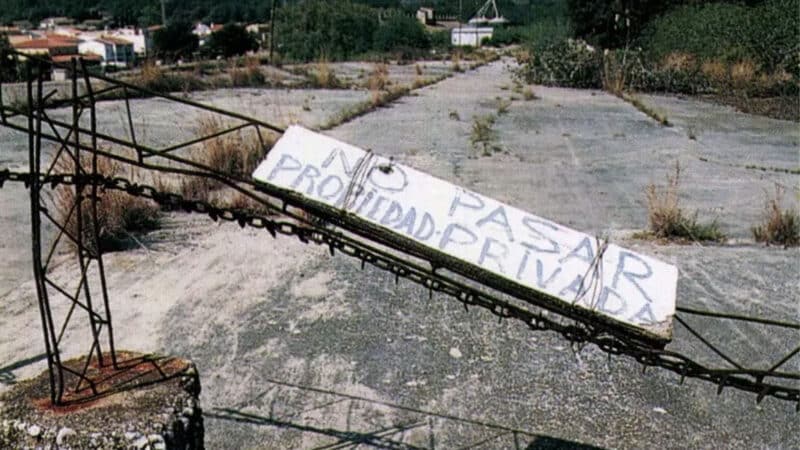

Autodromo Nacional was big news, a source of national pride for a country that had lagged behind industrial giants Britain and Germany and was determined to catch up. Sitges was meant to be a beginning. A pointer to a brighter future. It was to be a middle and an end, too. A microcosm, a litmus test of the problems and darker days to come.

Spain’s most ambitious motor sport programme began on October 21, Albert Divo’s Talbot 70 winning the voiturette Penya Rhin Grand Prix, held over 35 laps of the 9.2-mile Vilafranca road course. Fifth, in his first race outside Italy, was Tazio Nuvolari at the wheel of a Chiribiri 12/16. The Mantuan had a busy Iberian schedule ahead of him, for Vilafranca was just for starters.

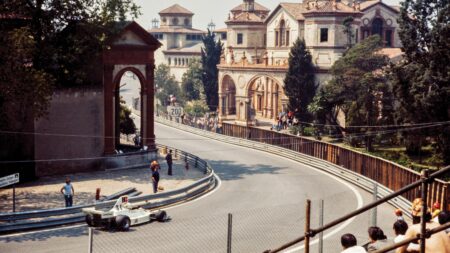

Sitges, the following weekend, was the main dish. And everything was ready. The crowd was impressive: 30,000, some ferried from the purpose-built train station to the track in purpose-built Model T-based coaches; others arriving in the 4000 cars parked on the infield-cum-aerodrome.

Early rain threatened the show, but afternoon sunshine saved the day: the first Spanish Grand Prix was go, albeit reduced to 200 laps from 300. There were five no-shows, including the Miller of 1922 Indy 500 winner Jimmy Murphy, but the seven starters thrilled the crowd, the ‘Fiat copy’ Sunbeams of Divo and Dario Resta slugging it out with Louis Zborowski’s Miller 122. Resta retired after 150 laps, but his team-mate upheld Sunbeam’s honour, winning by a minute after the blistering pace forced Zborowski to fit new tyres with just 10 laps to go. The Count’s consolation was a 45.8sec (97.49mph) international car lap record. It would never be broken.

And Nuvolari? He raced his 500cc Borgo in the Spanish Motorcycle GP, held the same day, over two 175-lap heats. He retired, but returned the next weekend to drive his Chiribiri in the Spanish Voiturette GP. This, in turn, was held the same day as the 200-lap Spanish Cyclecar GP (1100cc) was completed; it had been abandoned after 70 laps three days earlier because of rain. Robert Benoist led a Salmson 1-2-3-4 in the latter event, while Divo deferred to Resta in the former, missing out on a memorable Spanish hattrick by lsec. And Nuvolari? Fourth, after brake and exhaust problems.