Seppi would have been at a loss in today’s racing world. The notion of doing F1 alone, racing only 16 or 17 times a year, would have been anathema to him. In a typical season, he would routinely compete in F2, sports cars and Can-Am, as well as running the full grand prix schedule. A weekend without a race was a weekend lost.

In that respect, as in many others, he was very similar to Pedro Rodriguez, whose path he often — physically and metaphorically — crossed. For most of his career Siffert was regarded primarily as a sports car driver; good in an F1 car, outstanding in a Porsche. And the Porsche with which he belongs in my memory is not the fearsome 917, but the open 908 of 1969.

This was one light race car, a mass of tiny tubes and fibreglass, and I remember practice for the BOAC 1000kms at Brands Hatch that year, the way Seppi danced it round to pole position, three seconds inside any other Porsche time. Mesmeric.

Siffert and Rodriguez became team-mates when John Wyer took over the running of the factory Porsches in 1970. If Pedro had the greater natural talent, there was rarely much between them. And they excelled particularly at such as Spa-Francorchamps, places where a driver needed at least two of everything.

The late David Yorke, their team manager, was another who relished conversation of Seppi. “Amazing bloke. A typical day’s testing for him would entail driving all morning, then sinking two platefuls of goulash or whatever at lunchtime, washed down with a couple of steins of beer, then driving again all afternoon.

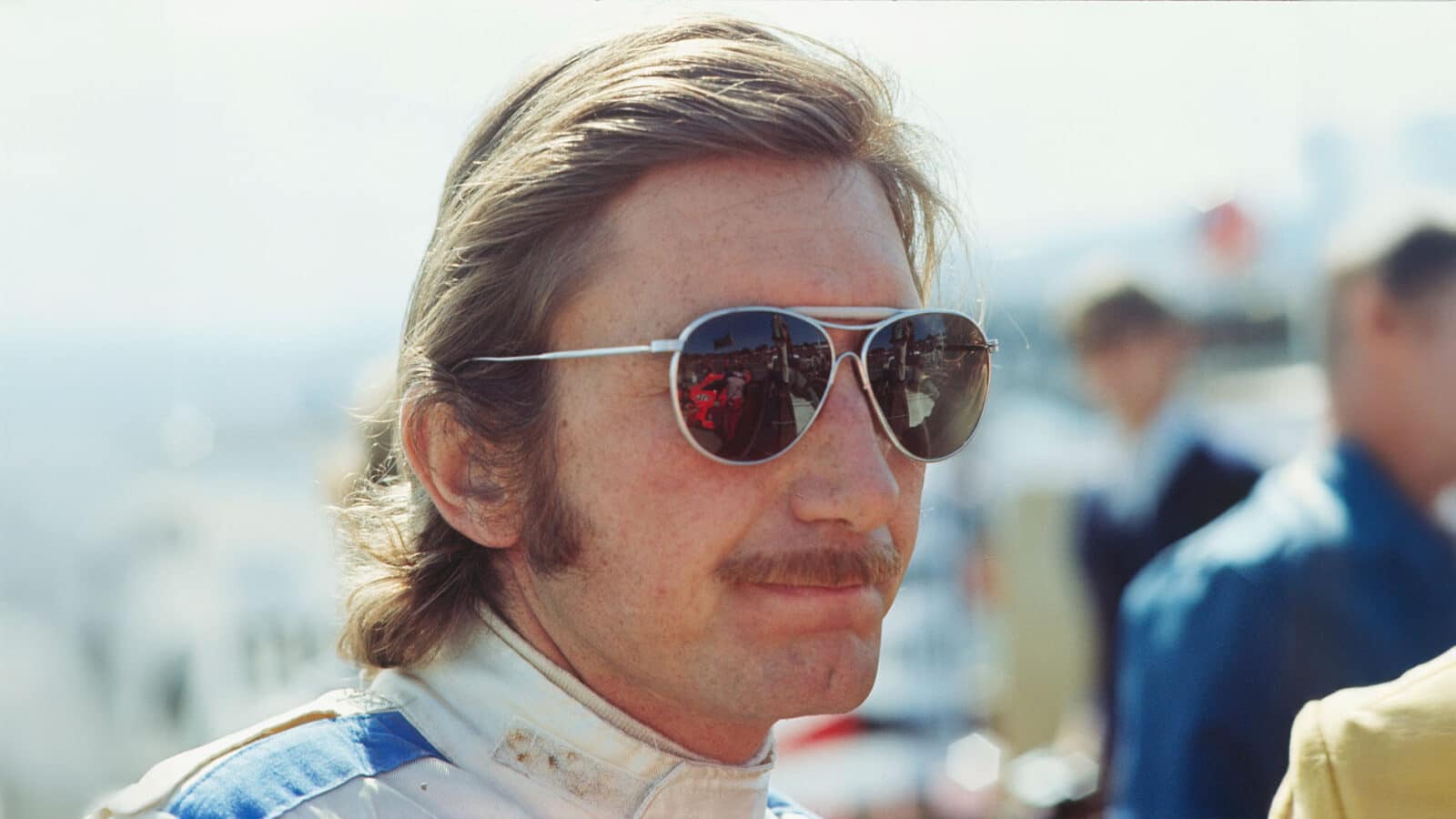

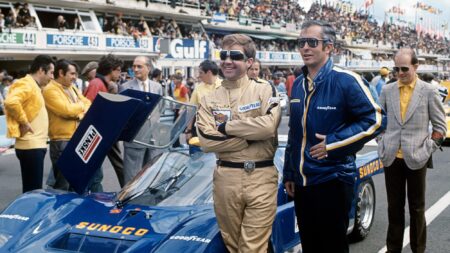

Some of the Swiss driver’s finest moments came in sports cars, driving both the Porsche 908 and 917

Getty Images

“Siffert was incredibly single-minded,” Yorke said. “I remember one occasion when Brian Redman came in to hand over to him earlier than expected. Seppi wasn’t even in the pit, but somewhere out the back. When he saw what was happening he ran to the back of the pit to jump over the counter, caught his foot on it, and went sprawling on the road. His overalls were ripped, and his knees torn to pieces, but he never gave them a glance. Hurled himself into the cockpit, and was gone! Amazing bloke…”

By this time Siffert had sadly parted ways with Rob Walker, for a drive with the new March team had been offered. Twice already he had turned down Ferrari, as this would have meant severing his ties with Porsche, but this new offer left him free to drive sports cars for whomever he wished.