“No,” said the lady at the tourist bureau firmly, “you can’t telephone Budapest from here. Impossible.”

An Austrian colleague tried to further our negotiations. “No good,” he said. “Her telephone operates only in a 151cm radius of here,” he replied. In my innocence, I asked why.

“To prevent communication,” he said, simply. “You are in an Eastern bloc country now, remember…” Communication was to be a problem in the Williams motorhome that weekend, too.

Architecturally, Budapest was – and is – stunning. These days, with a McDonald’s every 30 feet, you could be in any major city on earth. Back then, though, the shops conjured images of England in 1947, and the restaurants suggested food of a similar vintage. The wine, by way of doleful contrast, appeared to have been pressed only the day before. That said, the people were kindly and polite, and their enthusiasm for this new world of Grand Prix racing was rather touching. In the paddock they hovered close to the drivers, but were careful not to interrupt conversations. Finally, when they thought the moment right, they approached for autographs with carefully rehearsed English, addressing ‘Mr Warwick’, and calling Rosberg, ‘Sir’. Monza it most definitely was not.

If they appreciated the courtesy and warmth with which they were treated, however, the drivers were left cold by the Hungaroring, and that much has never changed. ‘Mickey Mouse’ even by the standards of today, 14 years ago it seemed a complete absurdity. In those days of the turbo era, when the cars qualified with upwards of 1200bhp and raced with 1000, still only a handful of drivers succeeded in lapping the place at over 100mph.

There were no straights worth the name, and an abundance of fatuously tight corners. As well as that, the track surface was ‘industrial’, which is to say that probably it would require little or no attention for 40 or 50 years, but provided no grip whatever.

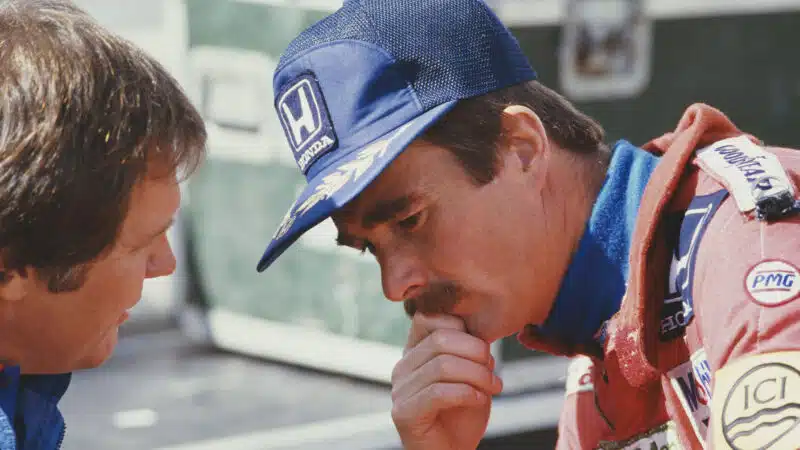

Piquet wins out, Mansell isn’t impressed

DPPI

Actually, this made for quite entertaining spectating, for the cars of the time had anyway a surfeit of power over grip, and Piquet and Senna, in particular, routinely proceeded through the first corner in gloriously abandoned opposite-lock slides. Ayrton took pole position eventually, with Nelson next to him, then Prost, Mansell and Rosberg. On race day 189,000 paid to come in, even though for most the price of basic admission was close to a week’s wages; this was, after all, the first major international sporting event in Hungary for 30 years. By nine o’clock, with the heat already building, they packed the hillsides.

In the warm-up, the McLarens of Prost and Rosberg set the best times, but afterwards Piquet – always a sandbagger sans pareil – confided to an Italian journalist friend that he had ‘found something’ in qualifying, that winning the race would be no problem. With two cars at his disposal, he had tried a different cliff, and found it markedly superior on this track where grip was scarce, but although he let on about it to his pal, he forgot to mention it to his team-mate.

Although Senna fought characteristically hard in the race, and led for much of it, the Lotus was not truly a match for Piquet’s Williams, which won by 18 seconds, with Mansell a distant — and disconsolate — third.