Selecting first – nearest to you and back on the H pattern – requires patience, leaning dog against dog until they acquiesce and mesh, otherwise this is a close-ratio, four-speed crash ‘box that puts those of 20 years’ hence to shame (John owns a 3-litre Bentley of which he is very fond but which, he says, proves this to be true). Sound familiar too? It will when even the lowest-of-the-low family buzzbox has a paddle shift and sequential ‘box in 2020. Now to balance that power, through that race-bred transmission (a transaxle, in fact), against the available grip º an equation as relevant to the Panhard as it is to this year’s Ferrari F1-2000. For this a racing driver needs, demands, clear, direct messages, which he can interpret quickly and respond to instantaneously. This is exactly what the Panhard provides. True, its front wheels flap alarmingly to the modern eye as its all-round semi-elliptic springs and friction dampers (neatly given a rising rate by a cam inside their body) snuffle and shuffle across the crown of the road, but every twitch, buck and bronc is fed, uncorrupted by excessive unsprung weight (no front brakes!) through to a wood-rimmed steering wheel that snuggles into the driver’s chest This is high-geared – less than two turns from lock to lock — and requires a bit more bicep on today’s tyres and surfaces than it probably did in its day.

Final drive trains relatively unstressed

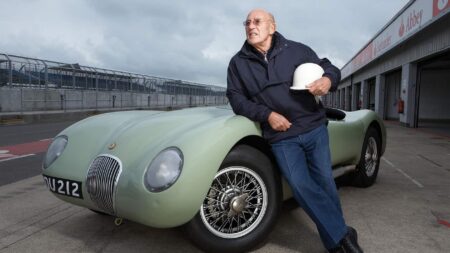

Richard Newton

The car now sits on wire wheels (designed by Mark, who prefers the warning of twanging spokes than the sudden snap of a failing wooden military wheel) and straight-sided tyres, as opposed to beaded edge, because of the extra safety their steel bead provides. That tiny contact patch remains the same, however. Which means traction can easily be broken. And the tail easily held. Grip and roadholding is, as you might expect, poor, but the handling is, as you might not expect, excellent. This car works for you. It turns in with remarkable alacrity and facility. Understeer is simply not an option; the twin, 35mm pitch, final-drive chains ensure equal grunt to both rear wheels and require, demand, you to be on the power at turn-in. Once in, chassis flex sees the inside rear lift slightly and smoke lightly as the car is driven on the throttle. Jean Alesi would have a whale of a time in it. Photographer Newton, following in a brand new Audi A6 estate, was stunned by the Panhard’s midrange punch and poise as we touched 70mph on the brief run to Bruntingthorpe.

Given a less populous country, driving it would be a straightforward affair. But crowded Britain needs, demands, brakes. Which is where the Panhard falls down; applying its ‘stoppers’ is akin to little more than a secondary lift. This anchor does not reach the bottom. The transmission brake is to be avoided at (almost) all costs, as this contracting shoe-on-drum affair, mounted between engine and transaxle, could easily become a transmission breaker. First port of call, therefore, is the handbrake (on the right, outside the bodywork) which is punched rather than pulled on. And left there – cast-iron shoes expanding onto steel drums. This allows the driver to declutch-blip-declutch down the ratios as the car is (imperceptibly) slowing: not so much heeling-and-toeing as palming-and-palming. Just before turn-in the fly-off handbrake is flown off with a flick off the wrist. This sequence seems the most logical method (the Walkers have been racing, sprinting and hillclimbing the car since 1980, so they should know) and was probably practised by the car’s original pilots. The long straights of the circuits of the time put a premium on long-legged power, but Dieppe was not without corners along its 47-mile length, and you can bet that Jo Siffert was not the first of the ‘last of the late brakers’.