It is poignant and apt that one who treats the Indy 500 with such reverence should go on to become one of the event’s true legends. First, however, he had to swallow the fact that nowhere is the ‘winning is everything’ adage more true than Indy.

“In ’67, I finished second in Al Retzloff’s car, behind Foyt. Yet the next day someone asked me where I had finished. I was amazed! That taught me there’s only one place – and that’s number one.”

And that’s precisely where Al’s brother Bobby found himself; having won the 1968 Indy 500 on his way to the USAC crown. Five years Al’s senior, Bobby had the gift of the gab to match his raw talent, and his wildness captured the bigger headlines. Eventually, however, quiet Al would out-stat big brother in all Indy departments bar pole positions.

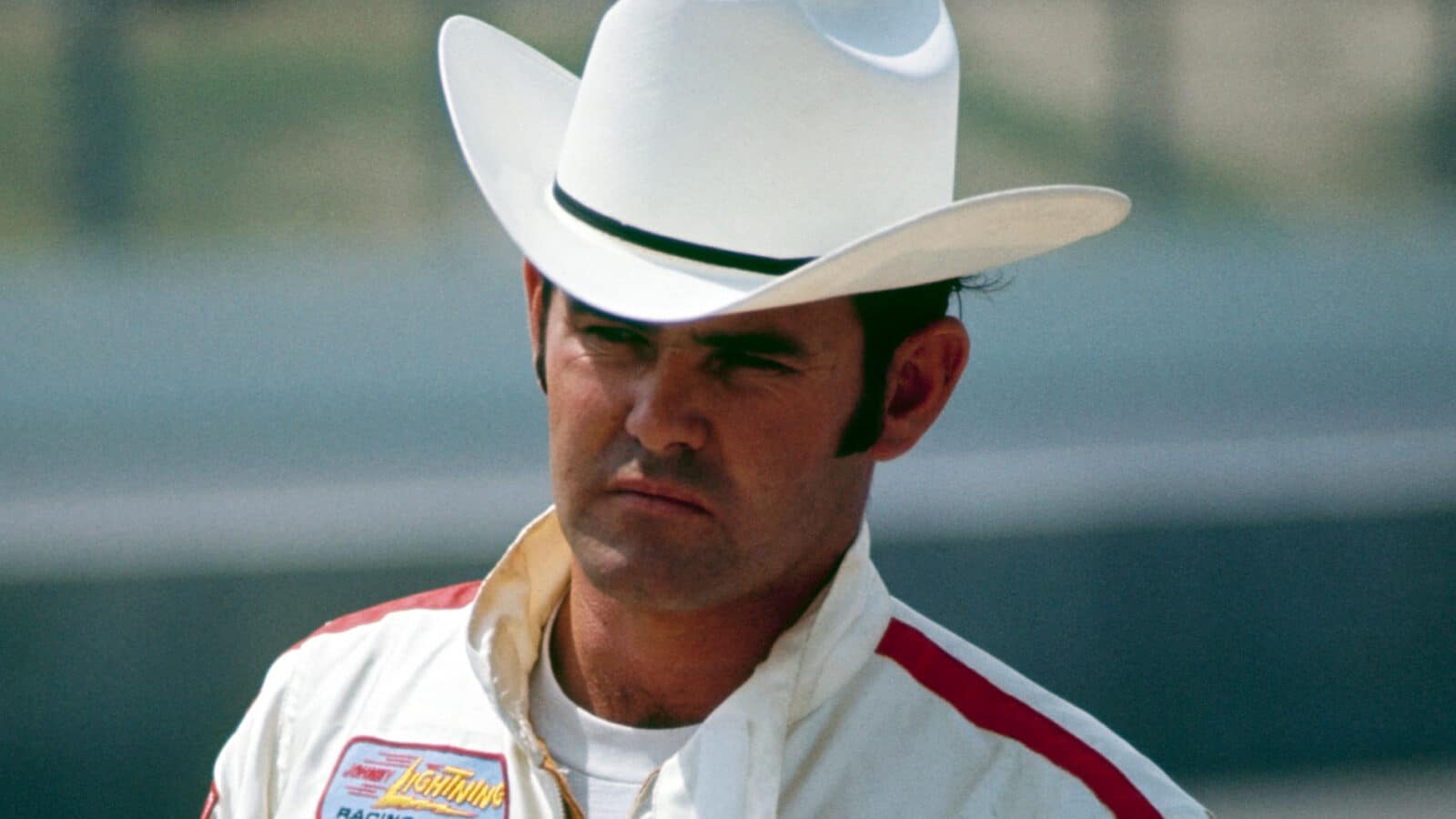

En route to first Indy win in 1970 – a day of pure domination

Getty Images

Retzloff quit the ChampCar scene in 1968, so Al, together with George Bignotti – one of US motorsport’s greatest crew chiefs – joined forces with Pamelli Jones and Vel Miletich who bought out Retzloffs assets. It proved a productive relationship. By ’70, the car had been reworked by ace aerodynamicist Joe Fukashima and was now called a Colt. Sponsorship from Topper Toys, who were attempting to steal a marketing march on Mattel’s Hot Wheels series, rendered the Colt-Ford the ‘Johnny Lightning Special’.

No-one else was in the running that year at Indy, and Unser led 190 of the 200 laps.

“You never know you will win Indy,” he says. “There isn’t a driver who can ever say that. But even before practice started we knew that, if we did everything right, we had a very good chance of running up at the front. But we did not know we could lead the amount of laps we did.”

In retrospect, it is less astonishing. Indy turned out to be the second of 10 wins for the Johnny Lightning car that season. Al captured the title with one of the more dominant ChampCar seasons. Like Mark Donohue in a Porsche 917/30, or Niki Lauda in a Ferrari 312T, man and machine had formed a perfect circle which no-one could break. At last Al was receiving proper recognition; if he was destined to remain in Bobby’s shadow for much of his ChampCar career, he at least was now much more than ‘the other Unser’.

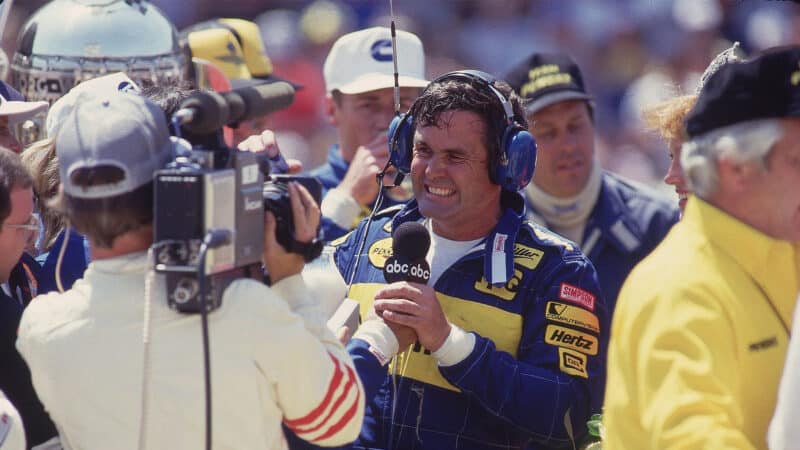

Unser took back-to-back wins after coming home first in ’71 also

Getty Images

This was ensured in 1971, when he scored his back-to-back Indy win (the last time this was done until Helio Castroneves this year).

“McLaren should’ve beaten us,” says Unser. “They had a 10-times better car, because their interpretation of the rules produced a huge rear wing and lots of downforce.”

Qualifying revealed all: Peter Revson’s works McLaren took pole at 178.69mph, Donohue’s Penske-run machine was second; Unser lined up fifth, unable to break the 175 barrier. On race day, Donohue pulled away from everyone until quarter-distance, when his transmission failed. And that should have left Revson with an easy win. Instead, he didn’t even lead a lap.