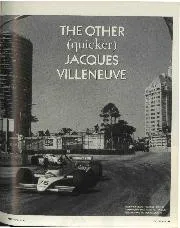

The year began with a trio of IMSA-sanctioned races in the USA, at Road Atlanta, Laguna Seca and on the infield road course of the old Ontario Motor Speedway. In Georgia, Villeneuve outlasted an early challenge from Tom Pumpelly for his first win, but the next round at Laguna Seca became the only race that he didn’t start from pole. A two-heat format established the grid, and a local driver named Dan Marvin claimed the first grid spot by winning the fastest heat.

In the final Marvin led early, but soon gave way to Gerber and Villeneuve. Gilles pressured the Mexican into a mistake at Laguna’s famous Corkscrew and drove away to the win, with Forbes-Robinson’s Tui second and Gerber’s Chevron third. Marvin, taken out of third by a backmarker, finished 25th.

By race three the relationship between Villeneuve and his team manager Ray Wardell had begun to solidify, giving the season its all-too-familiar shape. After his chief mechanic, Andy Roe, had trimmed his car out more than the others for the high-speed OMS layout, Gilles drove away from pole to win by 15 seconds from EFR, with Brack another 10 ticks back in third.

It’s this relationship between Villeneuve and the moustachioed Englishman Wardell which Rahal credits for their incredible success. “Ray came from the March F2 team and was just very, very good,” says Bobby. “He was all business and brought a whole new level of seriousness and preparation to that team. There’s no doubt in my mind that Gilles was tremendously talented, but Ray was able to take all that and channel it in the right direction. It was a very frustrating year for me as we had horrible mechanical issues, but obviously for Gilles it was a magical year.”

Villeneuve spins at Trois-Rivieres in a rare off-moment

Getty Images

The Canadian season opened in mid-May with the Player’s Alberta on the windswept flatness of Edmonton International Speedway, where a colourful race ensued as the first five ran nose to tail in the opening laps. Villeneuve led the queue in the familiar green Skiroule machine, trailed in ever-shifting order by Klausler’s white Traylor Lola, Brack’s fluorescent red STP Chevron, Rahal’s orange Shierson March and Gordon Smiley’s pale blue Fred Opert Chevron. Once the initial fireworks had been sorted out, however, Villeneuve ran home uncontested, with Brack second ahead of Smiley. Rahal retired early after an off-course excursion and Klausler lost third to a late tangle with lapped traffic.

From Alberta everyone headed west to British Columbia, where Loft scored his upset, then turned back east across the prairies into Manitoba. The Gimli airfield circuit had been the site of Villeneuve’s maiden Atlantic win the previous year, and he spent the afternoon duelling with Brack until the reigning champ spun out of contention just past three-quarter distance.

“The amazing thing about Gilles,” remembers Brack, “was that you’d think you had him beaten, you knew he was going into this corner in front of you way too fast. Then he’d go off and you’d think, ‘That’s it, I’m on my way to the chequered flag.’ But he had this ability to know which way the car was going when it was spinning so he could catch it going the right way. He had an extra ability, something special, there’s no doubt about that.”

The week before the next Player’s round, in July at the daunting Circuit Mont Tremblant near Ste Jovite, Villeneuve had an enormous accident while testing at the track in the spare car. Fortunately he escaped injury and his primary March remained untouched in the truck, so the race-weekend story could stay the same: pole position, dominant drive, race victory.

“I was on the front row with him at Ste Jovite,” recalls Klausler, “and at the start of the race he just drove away from us. His car was very light on the ground, and in the big downhill right-hand first turn I remember thinking he was going where I wanted to go, but I just couldn’t get my brain to make the car go there. It was disheartening. He was in a different league.”