Brett says, “I was not brought up with motor racing and my introduction came completely by chance when a friend suggested I join him on a trip to a New Jersey track called Vineland Motor Speedway, where some SCCA racing was taking place. Immediately the competitive nature of motor sports grabs you; I was a very competitive person and wanted to be part of it.

“I pestered a local driver called George Alderman and he helped me start practising with a Corvette at Bridgehampton. I took part in this drivers school, even though you had to be 21 and I was only 20. But I was born in November and back then we had a paper driver’s licence and I scratched off a 1, so it looked as though I was born in January rather than November!

“George was very encouraging and we became business partners and started an automobile dealership with a Rover franchise, then we got Lotus. Next, this new Japanese company called Datsun came along and we picked up that franchise and the dealership thrived. We sold it 25 years ago.

“We went halves on a Lotus 23, my first proper racing car, and in my first race at the Marlboro track I won. That was in the spring of 1966 and at the time I was a political science major at Princeton, so there wasn’t much time for racing. I was doing a thesis on south-east Asia and was in a hole because a lot of my assumptions were incorrect.”

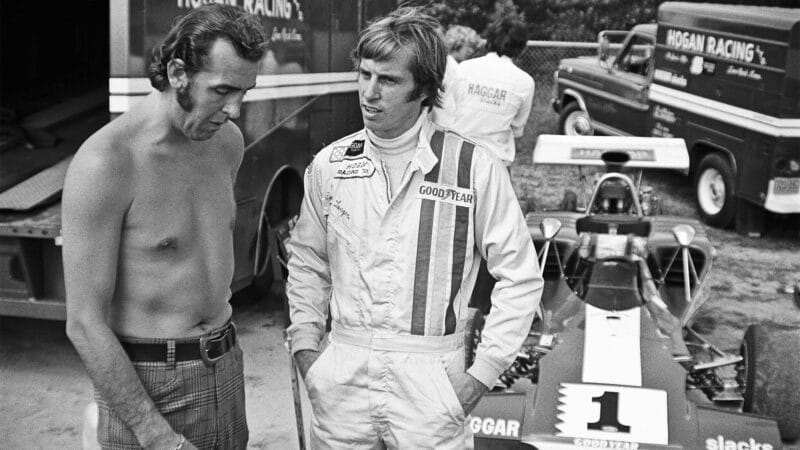

Lunger described his F5000 boss Dan Gurney as an “all-American hero”

Getty Images

By that autumn Lunger had graduated to the Can-Am series, racing a Lola T70 – quite a start to his career, “I benefited from not knowing what I was doing,” he says. “Sometimes you gain from being clueless and I had no preconceived notions. I didn’t think Jimmy Clark was particularly impressive. In my arrogance I thought, ‘I can race these guys’.”

The following year Lunger turned his back on Princeton, without getting his degree, and signed up for the military, a decision that did not please his parents. “Things were beginning to heat up in Asia and I was brought up to believe that to be a citizen of the United States you had an obligation to serve the country,” he says. “If you are going to this sort of thing you might as well go with the best and that was the marine corps.”

Lunger signed up as a private in South Carolina. “They didn’t know I had come from Princeton, or who my family was – if your drill instructor knows you have a brain you could be in big trouble. Anyway, I went through boot camp and at one point they discovered I could spell my name the same way twice so I was enlisted on a commissioning programme. Frankly they were losing officers pretty quickly, so the next thing I knew I was a second lieutenant and heading off to Vietnam.”

All this rather messed up his blossoming racing career, although he did fit in some more Can-Am races in both 1967 and 1968. “In a way I am glad I joined the marines,” he says, “because the Vietnam tour of duty did more to shape my character and personality than anything else I did in my life. But in another way I am sorry because it hurt my racing career, without question.”

Leading the 1974 Riverside F5000 race

Getty Images

Lunger was injured close to or behind enemy lines near the Laos border. While back in the US he started to train recruits, but was also enrolled in what was unnervingly called the Survival Evasion Resistance and Escape School. He was put through a simulated prisoner of war programme of sleep deprivation and was even water-boarded. “They make it as realistic as possible; this is not a teaching environment “ he says. “It broke some guys.”

He had to decide whether to continue in the Marines or return to full-time racing, and chose the latter. “I was very close to going back to Vietnam for a second tour,” he says, “and if I had taken that path the odds are I wouldn’t have survived. I decided I wanted to give motor racing a shot. I didn’t want to wonder what might have happened.” He left with the rank of captain, just a pip away from major.

“I didn’t have money to fly to races, so I drove everywhere in a van”

Out of uniform Lunger was able to put together a sponsorship deal with a pharmaceutical company that made a hangover cure called Quick Over and bought a Formula 5000 Lola T192. In only his second race in the car – and only his second single-seater race – he finished on the podium at the Monterey Grand Prix, behind David Hobbs and Frank Matich. Hobbs went on to win the title, but Lunger acquitted himself well and finished third in the championship.

Lunger’s budget was tight. “I didn’t have enough money to fly to races,” he says, “so I drove everywhere in a van. But this meant I would get into town early. I’d look up the name of the local TV and radio stations, call them up and say my name real fast, so they weren’t quite sure who I was, say I was coming to race and got on the air, promoting myself, my sponsor and the event. That got the attention of the L&M PR guy Rod Campbell, and he would later help my F1 career.”

In 1972-73 Lunger raced alongside Hobbs in Carl Hogan’s crack F5000 team, bringing Haggar Slacks backing. “It was a special time,” he says. “David was great fun and a very strong driver. Those F5000 cars were beginning to be very competitive and Carl set up a great team with equal equipment.” Campbell, meanwhile, saw F1 potential in Lunger and decided he needed some European experience. So in 1972 he was able to structure a deal whereby Lunger did the majority of the European Formula 2 season in a Space Racing March. The results were mixed, with sixth places at the Nürburgring and Monza plus a fourth at Mantorp Park being the best results.