The march to many cylinders began in 1960, when engine designers Hans Mezger and Hans Horich penned a flat-eight, 1500cc engine for Porsche to take grand prix racing. The engine entered competition in 1961, and helped Porsche secure third place in that year’s constructors’ championship, but it could not topple the might of Lotus and Ferrari. However, the eight-cylinder made an ideal basis for a sports car motor, and in 1962, the 718 W-RS Spyder, and hardtop 718 GTR entered the fray. As the decade progressed, Porsche’s efforts ramped up, culminating in the monstrous, 4.5-litre, flat-12 powered 917.

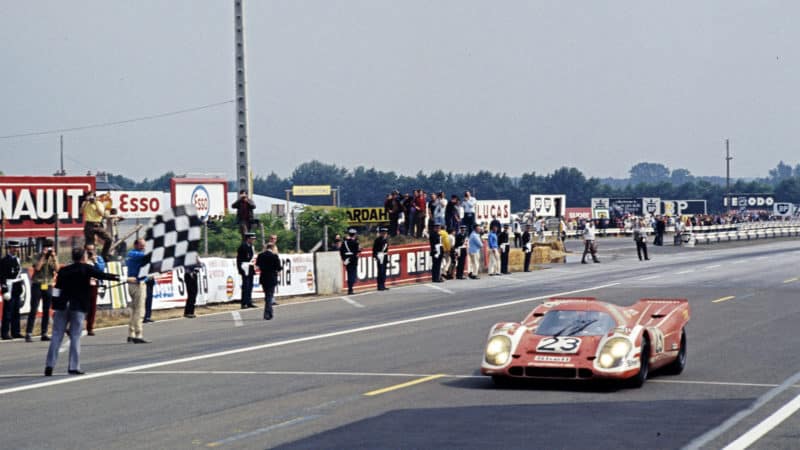

Porsche played a blinder with the 917. A rule change in sports car racing for 1968 capped prototype cars’ engine capacity at 3.0-litres. Meanwhile, production cars were permitted 5.0-litres, the logic being that no one would be mad enough to build the 50 cars required to qualify a prototype as a production machine. However, in late ’68, that figure was cut to 25 and, Ferdinand Piech, Ferry’s nephew and in charge of the company’s racing programme, decided Porsche would construct a 4.5-litre prototype and churn out enough of them to attain production status.

Mezger created an engine that was dripping with innovative engineering features. Sandwiched within its magnesium alloy crankcase was an eight main bearing crank, with a centre feed oil supply and each pair of connecting rods sharing a common journal, allowing for the length to be kept relatively short. Despite this, vibrations due to the natural harmonics of the crank were still a concern. Mezger’s solution? Take drive from the centre of the crank where there were effectively no vibrations.

A 22mm shaft (later changed to a 24mm, titanium production) ran along the bottom of the engine to the clutch, driven via a pinion at the centre of the crank, while the cam and distributor drive used a shaft running along the top of the engine, which also drove the cooling fan, mounted flat atop the crankcase. In a paper he wrote on the engine’s development in the early 70’s, Mezger remarked that, “there is no doubt that the more complex central drive of the 917 was worthwhile. Almost no problems were encountered during the development of the different [ancillary] drives and this is mainly due to the central drive design concept.”