“I couldn’t get to the accident,” said Watkins, “first because I didn’t have a car, second because, when I tried to go on foot, the police wouldn’t let me through. So I went straight to the medical centre, and received Ronnie there. He was quite conscious and rational. We put a splint in his legs, and we put a drip up. That was all done correctly, but there was absolutely no crowd control – while I was working on Ronnie, a photographer pointed a camera between my legs, to get a picture of him. I kicked him…

“When I started to write descriptions of how the medical centres needed to be, security was one of the requirements, and proximity to the helicopter was another one – we had to carry Ronnie through the crowd to put him in the helicopter…

“At the time my position in the sport wasn’t official, in the sense that I was employed by FOCA – by Bernie – rather than by the FIA. After Monza he decided that he and I had take responsibility for circuit rescue, that in future a medical car had to be available, enabling me to follow the first lap, and to go to any accident. That was a huge step, from being there to give medical advice to being actively involved in the rescue.

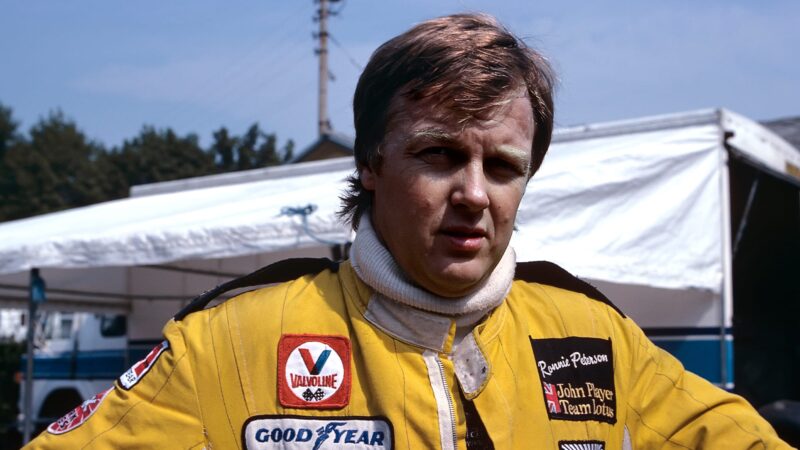

Peterson at Monza in 1978

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

“We carry a fair amount of stuff in the medical car – it’s not an ambulance, obviously, but a quick road car to get us to the accident scene fast. The primary requirement, of course, is equipment to stabilise an injured driver, to keep his blood pressure good, and his pain controlled as much as possible. So we carry equipment to measure blood pressure, and to keep the airways clear. As well as that, there’s a ventilation machine with oxygen, a special mattress, for back injuries, and equipment for dealing with spinal damage.”

Throughout those years, during which time Watkins literally transformed medical practices in motor racing, I never quite understood how he managed to combine that with his work at ‘The London’. Being Sid, of course he found a way: “I was chairman of the department, so I wrote the rota. There was myself and one other consultant, and we did 24 hours on, 24 hours off, and alternate weekends. I did the rota so that I was off for race weekends – I could leave Thursday night, and come back Sunday night, in time for operating day on Monday. So I’d do 26 weekends on call at the hospital, plus the Grand Prix weekends – I used all my annual leave for the races, so I basically had no holidays at all…”

Whether or not he paid Watkins what he was worth, Ecclestone well knew the value of the man he had hired, and indeed it was a fact that down the years the Prof was the only man in the paddock – who knows, the world – to whom Bernie always deferred. Very different people they may have been, but crucially they shared a profound distaste for red tape, an ability to get things done.

“Only once did Bernie try it on with me,” Sid said, “and that was at Imola in 1987, when Nelson Piquet went off at Tamburello in Friday practice. Two hours after the accident he didn’t even know he was a racing driver, so obviously there was no way I was going to let him near a car again that weekend.

“Next morning Bernie says maybe I should let Nelson do a few laps – and if he felt all right, he could go into qualifying. I said, ‘Bernie, if Nelson gets into a car, I’m leaving the circuit – and I won’t be back.’ He said, ‘Yeah…all right then…’”

These days all circuit medical centres must have an intensive care unit equipped to modern university hospital or major trauma centre standard. They must have emergency equipment, too, to deal with such as bleeding from a major artery. Indeed, many now have full operating theatre capability, to be used in extremis, and there are also X-ray departments, ultrasound, and so on, together with at least two intensive care beds.

These centres are inspected on the Thursday afternoon, and each morning thereafter, and on Thursday, too, there is an extrication exercise, so that the local spinal rescue teams are conversant with the modern F1 car, and the way the ‘extrication seat’ is removed. Before any practice session or race, the facilities around the track are inspected, including intervention cars and ambulances, to make sure everything, and everybody, is prepared. All of this came to be at the behest of Sid Watkins.