“One of the things that Donohue believed was that you can determine the mechanical quality of a car by going around this big circular piece of tarmac – and then when you get that result, you add the bodywork!”

Watson thought the team were onto something with the PC3, helping it build up two examples for the ’76 season – but then the American outfit was thwarted by unforeseen circumstances.

“A regulation change came in early in ’76 which meant that the tall air boxes were removed and also the wing rear wing position came in close to the car,” he says. “All that screwed up the aero package on the PC3 – it never had the same kind of balance as it had prior in its original configuration.”

To fix the solution, the ever pragmatic Penske – dubbed ‘The Captain’ for his industrious nature – cast his eye over the rest of the grid for the solution.

“Roger said ‘Let’s build our car again’, Watson says. “Looking at other cars, the McLaren, he said ‘I want you to put a big spacer in between the engine and gearbox like an M23 and put on a normal set of normal canard fronts wings – and the car was transformed.”

At its first race in Sweden, the team were lost, but then two top-three finishes in the next three races – Watson’s very first F1 podiums – justified The Captain’s decision to go back to the drawing board, the result being the PC4.

“The car did all the things it should have been, but initially didn’t,” Watson says. “At the French GP, Brands Hatch – and then it all came together in Austria.”

The PC4 helped Penske get back on the pace

DPPI

Today, Roger Penske has a sprawling business empire. Employing over 60,000 people, as well running IndyCar, NASCAR, and also Porsche’s sports car teams on the weekend, the Pennslyvanian has interests worldwide.

However, hard as it is to believe now, Penske was still then a relatively poor relation on the F1 grid in the mid-’70s. As a result some performance-related privileges afforded to teams like Ferrari and McLaren were hard to come by – but at the Österreichring, the boys from Pennsylvania lucked out.

“Everybody was running crossply Goodyear tyres,” Watson explains. “And one of the difficulties with these was getting continuity in the circumference of the tyre.

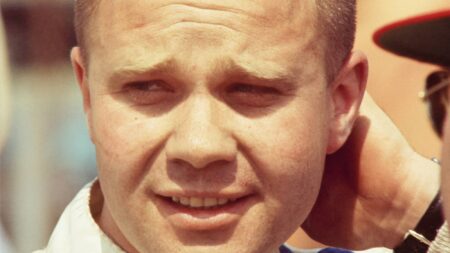

Watson was James Hunt’s closest challenger in qualifying, lining up P2 on the grid

Grand Prix Photo

“If you were a ‘contracted’ Goodyear team, you got first dibs when the tyres were made available. Guys from Ferrari, McLaren, Lotus and Tyrrell got in first and took the best matched front and rear pairs.

“Depending on your status in the field, you ended up getting what was left. We didn’t have different compounds then.”

“The basic handling was transformed – it became a racing car”

For once though, Penske found the ‘magic’ set.

“In Austria our tyre guy Jerry, out of all the sets of tyres I could get, ended up with one which was just unlike anything else – I don’t know what it was.

“There were fundamentals that were hidden in the car’s performance, but you put these tyres on and it came alive. The basic handling was transformed – it became a racing car.”

James Hunt was the class of the field in qualifying and thus on pole, but as a result of the rubber revelation, Watson was second – the only other driver to get within a second of the McLaren driver.