Marko was competing at an Austrian hillclimb in ’69 when he was approached by a local fan. The guy’s name was Dietrich Mateschitz. He was a couple of years younger than Marko but knew all about him. He idolised Marko’s friend Jochen Rindt – then F1’s fastest, most intoxicatingly exciting driver, who had converted a big chunk of the nation’s population into motor racing fans, just as would Verstappen do in the Netherlands many decades later. Rindt’s success in F1 had even sparked the creation of the country’s own race track, the Österreichring, and the Austrian Grand Prix was going to return to the calendar the following year. All on the back of the inspirational, swashbuckling style of one driver (managed, incidentally, by entrepreneur and failed racing driver Bernie Ecclestone). Young Mateschitz was just one of so many new fans of F1 in his country. Sounds kind of familiar from the era of Max, doesn’t it? Mateschitz and Marko became firm friends.

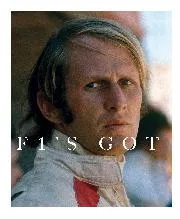

Marko was ‘The Man’ in Formula Vee in 1969. He’d followed his childhood buddy Rindt into racing, albeit a few years behind once he’d gained his law doctorate. Now Marko was making his way up the ladder, fast and ambitious and making up for lost time. But at the Formula Vee support to that year’s German Grand Prix at the Nürburgring Nordschlife, his dominance of the category was threatened by a 20-year-old upstart, Lauda. The younger guy in the privateer car set pole, marginally faster than Marko. With the F1 teams looking on, this was an unwelcome development in Marko’s career trajectory. They left the others far behind in their fierce duel that day, one in which Marko had to resort to showing Lauda the grass on the last lap in order to win. The third-place guy was a minute behind. The atmosphere on the podium was reported as frosty and there was talk of a protest. It came to nothing, but their long rivalry had begun.

Marko, Lauda, Wolff and Verstappen at birthday celebration for Bernie Ecclestone at the 2016 Mexican GP, months after the Dutchman’s remarkable first win

Getty Images

With the death of Rindt in qualifying for the 1970 Italian Grand Prix, Marko and Lauda represented Austria’s future F1 hopes. Although they made their F1 debuts at the same race (Austria 1971), Marko’s career had more momentum. He’d won that year’s Le Mans 24 Hours driving for Porsche and had been recruited by BRM for the rest of the year and into ‘72, whereas Lauda had rented a March for a one-off at his home track, the Österreichring.

Marko’s parallel sports car and F1 programmes continued into ’72 and after a sensational performance for Alfa Romeo at that year’s Targa Florio he was invited by Ferrari to stand-in for the injured Clay Regazzoni at the Österreichring 1000kms. He led for a time and impressed Ferrari sufficiently that by the time of the French Grand Prix a couple of weeks later, he had in his briefcase a Ferrari contract for F1 and sports cars in 1973. At Clermont Ferrand, he’d qualified his BRM on the third row and was dicing with Ronnie Peterson’s March when it threw up a stone from its tyre straight through Marko’s visor and into his left eye. He pulled the car over to the side before passing out with the pain. The loss of the eye and with it the great career: no F1, no Ferrari.