MPH: To the man trying to fill Christian Horner's shoes: good luck!

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

“We’re the best, right? Formula 1 is the best, and we don’t need anything in it that isn’t the best…

“People going on about only 19 or 20 cars in the race… OK, so what? The size of the field doesn’t bother me at all. It is much better for us to have a smaller, better quality grid than to have a lot of makeweights. We’re in the quality business, not quantity…

“What I want to get away from is breeding people who shouldn’t be in Formula 1, which we’ve got at the moment. Why are they here? Because they thought it was easier than it is – and if they were going to die, they should have done it in a dignified way. They should have pulled the blinds down, and said, ‘We did our best – but we couldn’t cut the cake’…

“What I don’t like is people walking around with begging bowls, and crying as if it’s everyone else’s fault. We should never have let in people like that in the first place, and it’s my fault for allowing it. If they hadn’t come in, we wouldn’t have had the embarrassment of them going out. I’m sorry if that sounds harsh, but it’s not Formula 1’s problem, any more than when anyone else goes out of business…”

The words, it will not surprise you to learn, are from the mouth of Bernard Charles Ecclestone, but they were not, as you might reasonably assume, uttered within the last few days. Rather they come from an interview I did with him at the French Grand Prix – remember that? – in 1995, and I reproduce them here to show that essentially nothing changes. The struggling teams to which Bernie was then referring were Simtek and Pacific, but he might have been speaking of Marussia and Caterham, both of which have gone to the wall, with – apart from anything else – the heartbreaking loss of hundreds of jobs and livelihoods.

These two teams came into F1, together with long-gone HRT, at the beginning of 2010, but quickly came to see that it wasn’t quite as they had been led to believe.

The situation rather reminds one of Britain’s entry into the European Economic Community in 1973, when prime minister Edward Heath conned us all into believing that this was nothing more than a trade agreement. In a referendum the following year to decide whether or not the UK should remain in it, I was one of the 67 per cent who voted in favour. Had I been bright enough to anticipate that the EEC would metamorphose into the European Union, that a sizeable chunk of the governance of this country would pass into other than British hands, I would have put my cross elsewhere.

Staying with this train of thought, let us go back to Formula 1, to the economic meltdown in the autumn of 2008, after which manufacturer teams like Toyota and BMW joined Honda in concluding that their immediate priorities lay elsewhere, and took their leave of Grand Prix racing.

That left just nine teams – 18 cars, which is what we find ourselves with now – and new ones were urgently sought, not least because lucrative contracts depended on a minimum number of cars, and who knew how many others might be lost?

After Max Mosley, then President of the FIA, had declared that if the sport were to survive, the imposition of some kind of budget cap (initially set at an unfeasibly low £40m) was a necessity rather than an option, three new teams – Lotus (which later became Caterham), Virgin (later Marussia) and HRT – took the plunge, further encouraged by the availability of ‘bargain’ engines from Cosworth.

Now, five years on, all are gone, and if it has to be said that their collective achievement – a total of two world championship points – was indeed modest, none should be surprised, not least because they were initially seduced into F1 by what proved – perhaps inevitably – to be an empty promise. While no one with half a brain could dispute Mosley’s contention that the costs of F1 were – and are – unsustainable, the sport has yet again demonstrated its eternally lamentable propensity for putting short-term vested interest before common sense, let alone the common good. Think Brazilian rain forests.

No one can deny that, in the course of his 16 years as President of the FIA, Mosley presided over much that was good in motor racing, most notably in substantially improved safety, but he was also the man who sold the commercial rights to F1 – at a car boot sale price and for a ludicrous 100 years – to Ecclestone.

It has long seemed to me that virtually all the ills of the contemporary sport may be traced back to this unholiest of deals. Soon after its announcement I had what was to be my last conversation with Ken Tyrrell, then in the final throes of cancer, but still feisty: “You wait,” Ken said. “Bernie’ll flog the commercial rights on to a bunch of bloody asset-strippers…”

And lo, in 2006 it was announced that Formula 1 was under new ownership, CVC Capital Partners having acquired it for around $2 billion, while employing Ecclestone to continue to do the deals.

Once at the helm, CVC lost no time in getting down to what ‘private equity companies’ do best, milking its new cash cow with both hands, while keeping its outgoings – payments to the teams, in other words – as low as it could get away with.

In 2008 there did seem fleetingly to be some light on the horizon, when the F1 constructors, quite reasonably angered by this situation, got together in Maranello and actually discovered some unity, thereby setting aside the habits of a lifetime. The formation of the Formula One Teams Association was announced, and I came away from its inaugural press conference, in Geneva the following spring, much encouraged.

Ha! I should have known better. Ecclestone’s ability to ‘divide and rule’ long ago went into the lexicon of Formula 1, and he wasted little time in swatting away this new, potentially bothersome, association. First, he reached a ‘revised financial accommodation’ with Red Bull, whose resignation from FOTA swiftly followed, and then did the same thing – with the same result – with Ferrari. Although FOTA struggled on for a time, now devoid of a unanimous voice, its potential powerbase was gone and ultimately it was quietly dissolved.

What the episode had demonstrated, however, was that the chequebook of CVC/Ecclestone could be pressed into service if it were considered – as on this occasion – that circumstances demanded it. For something as trivial as keeping alive small, financially-starved, teams – lately Marussia and Caterham, and potentially Sauber, Force India and Lotus – it remains firmly closed, and if the business increasingly comes across as a callous and avaricious monster that’s because it is.

In Austin, where Marussia and Caterham were newly absent, and the surviving small teams extremely angry, I was amazed to hear Ecclestone for once sounding almost humble. “The problem is that there’s too much money being distributed badly – probably my fault,” he said. “But like lots of agreements people make, they seemed like a good idea at the time. Frankly, I know what’s wrong, but don’t know how to fix it. If the company belonged to me, I’d have done things in a different way because it would have been my money I was dealing with, but I work for people who are in the business to make money.”

Gee, d’you think?

Donald McKenzie and Nicholas Clarry of CVC

There have been moments over time when people have suggested that Bernie, too, might just be ‘in the business to make money’, but they have always cut him some slack in acknowledgement of the fact that he has built the business – good and bad – into what it is, and if he has become inordinately rich along the way so also have they. Some of them, anyway.

CVC is a different matter: from the outset the company has only leeched money from Formula 1, while contributing to it precisely nothing. And it is in this position only because Ecclestone – in happy receipt of his knockdown deal with Mosley – chose to sell the business on, just as Tyrrell had predicted.

If the little teams were in future to get a fairer shake, Ecclestone suggested in Brazil, it had to come not – Heaven forfend! – from CVC, but from the major teams, who would be required to make a financial sacrifice.

To put it mildly, such a thing seemed unlikely: at the beginning of the year, after all, the self-serving and ill-named ‘F1 Strategy Group’ – which includes Bernie and the rich teams – declined a renewed attempt to introduce a cost cap, and FIA President Jean Todt admitted he was powerless to do anything about it.

At the same moment Ecclestone launched his farcical plan to award double points at the last Grand Prix of the season, and none of those present had the balls to take issue with him, so it was a jolly good meeting all the way round.

If the small teams never got the budget cap they anticipated, so also they eventually had to face the fact – given the major rule changes introduced this season – of vastly more expensive engines.

In my opinion, the move away from the normally-aspirated V8s – which made a lot of noise but were otherwise uninspiring – to the ultra-complex hybrid ‘power units’ of today was not only inevitable, but also a necessity. As if we didn’t know it, the world is changing, and if it were not to become a technological backwater F1 had to change with it. The dinosaur V8s were of no further interest to any engine manufacturer, save Ferrari, and if the rules had remained unchanged Renault and Mercedes would ultimately have quit, while Honda would never have countenanced a return.

If the change had to come, the stark reality was that the immense cost of developing the new power units was passed on to the teams, whose engine bills thus increased threefold.

In my estimation, the new rules have improved F1 immeasurably, the spectacle – and the quality of the racing – better by far in 2014 than for very many years. The new engines produce a lot more power than their predecessors, while using considerably less fuel, and that is something about which the sport should be shouting from the heavens. As it is, all we have heard from Ecclestone and his acolytes is endless complaints that they don’t make enough noise, and now there is even, from some in Bernie’s camp, the risible suggestion that we junk the hybrids and dust off the V8s! Ye gods…

If, with regard to the little teams, Ecclestone came across as contrite in Austin, he sang a very different song at Interlagos a week later. Rumours of a £100m ‘fighting fund’ to help keep such as Sauber, Force India and Lotus afloat were now discounted, and Bernie was back to his familiar ‘begging bowls’ routine.

At the same time the major teams, for all their financial security, found a way to escalate a falling-out between themselves. It has been running a while now, and concerns how much the ‘freeze’ on engine specifications should be relaxed for next year. Initially Mercedes, having done a conspicuously better job than their rivals, agreed to go along with a move that would not be in their interests, but there has now been a change of mind, and Renault and Ferrari, together with the teams who use their power units, are extremely displeased. Given that unanimity is required for change in 2015, but only a majority vote for the year after, the threat is clear: allow a partial thaw of the freeze next season, or we’ll go for a much more substantial – and expensive – one the year after. I never knew Fort Knox had a playground.

It is all so unedifying, the constant dissension, the bloated greed of those at the top of the sport and their ‘let them eat cake’ attitude to those at the other end. The fact that we have had a magnificent grand prix season is being submerged by discord and self-interest, and I, for one, am heartily sick of it.

Let me make a couple of points in conclusion. First, having suggested in Austin that he knew what was wrong, but didn’t know how to solve it, by the time of Interlagos the following weekend Ecclestone was back to his normal bullish self: “The way forward,” he said, “is very easy – don’t spend so much. We’re giving the teams collectively $900m (£566m) a year, and that’s enough.”

Give or take a quid or two, this is also the amount drained from F1 each year by CVC.

Second, to those who suggest that the small teams are of no account, and serve little purpose, let me recall a moment in the press room during practice at Monaco in 2001 – a second or three of in-car footage, of lightning fast hands, at the exit of Casino Square. “Who the hell is that?” we gasped. The car was a Minardi, the driver Fernando Alonso.

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

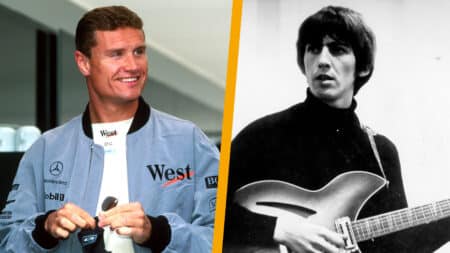

Former McLaren F1 team-mates Mika Häkkinen and David Coulthard are set to renew old rivalries in a new Evening with... tour – they told James Elson all about it

In Formula 1, driver contracts may look iron-clad on paper, but history shows that some of its biggest stars have made dramatic early exits

Former McLaren F1 ace told James Elson about his private audience with The Beatles' George Harrison, who played an unreleased grand prix-themed song