The car was completed only weeks before the ’97 season began, having run next to no mileage.

Vincenzo Sospiri and Ricardo Rosset were in the car for the season-opener in Melbourne, but both found the car to have too much drag, not enough downforce and had trouble getting its tyres up to temperature.

The two were 11.6sec and 12.7sec off the pace respectively, predictably failing to qualify.

The team travelled to Interlagos for the next round, before Mastercard decided to withdraw its support, leaving the cars stuck in the garage the entire weekend.

Lola withdrew from the world championship thereafter, and the famous racing car constructor would never again enter F1.

DAMS GD-01 – 1995

Jean-Paul Driot poses with the stillborn DAMS GD-01

Grand Prix Photo

In 1994 DAMS announced its intention to build and race its own F1 car, the GD-01, for the ’95 season.

Unfortunately for DAMS, Larrousse and Ligier were already hoovering up French motorsport investment, making sponsorship hard to come by.

Matters were made more difficult by the fact that the FIA changed the design rules for ’95 after the deaths of Roland Ratzenberger and Ayrton Senna, forcing DAMS to revise its car.

A deal with the ailing Larrousse squad to run the car in ’95 fell through, but the GD-01 was ‘launched’ at Circuit de la Sarthe, near the constructor’s Le Mans base, anyway.

Fitted with a Cosworth ED engine, Jan Lammers and Erik Comas tested the car at Paul Ricard, which was proving not up to making the 107% of an estimated ’95 pole time. More French Francs were needed to develop the car, but there weren’t any, and the project was eventually abandoned.

Dome F105 – 1996

The Dome F105 set respectable times for a new car with a rookie test driver – but lack of funding stymied the project

Dome

The Japanese Dome firm established itself as a limited production car company in the late 1970s. By the early ’90s it decided it wanted to aim for the very top with F1. The Jilotto Design house was established to help pen the car and with Mugen-Honda coming onboard to supply engines, it was rumoured that Honda was using the project to test the waters for its own works F1 team. This was rebuffed by Dome, however.

The F105 was first rolled out in late ’95, and in testing at Suzuka in late ’96 the car was almost 7sec off Jacques Villeneuve’s Williams-Renault pole time set the previous season and 0.3sec off the 107% rule required to start a race. With a Japanese rookie driver Shinji Nakano driving a car that was still in development and according to some had “spongey brakes”, this was fairly impressive.

As so often the case though, the money ran dry. A proposed ’97 F1 debut was pushed back as the team searched for sponsorship. Infamous future Arrows F1 investor Prince Malik Ado Ibrahim was brought in to both invest and try and source more money, but to no avail. When Dome got wind that Honda had its own works project in development – likely taking most potential investment from Japan – the independent squad decided to call it a day.

The car did have some lease of life in competition, as it was the basis for the Playstation 1 game F1GP Nippon.

Lotus 112 – 1995

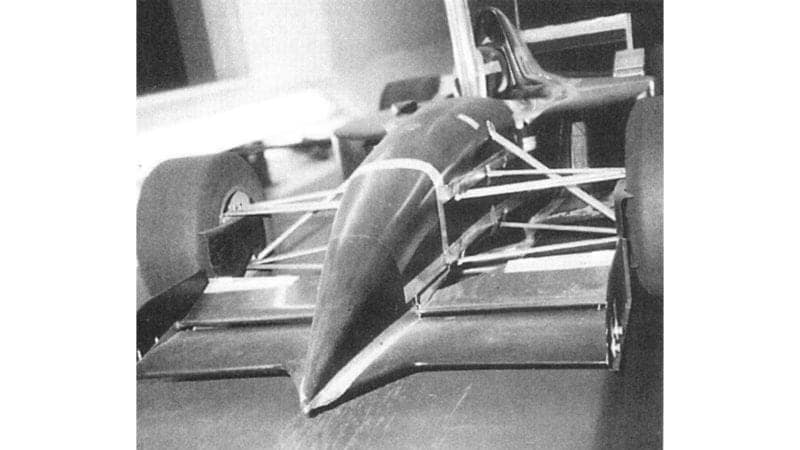

Lotus 112 remained an unrealised concept – this wind tunnel model was as much progress as it made

Chris Murphy

Before Team Lotus folded at the end of 1994, it was pressing ahead with plans for a ’95 car, the 112.

The car was designed by Chris Murphy and was thought to have been intended to take a Mugen-Honda engine, the power unit’s potential shown by Johnny Herbert when he qualified a Honda-powered Lotus fourth at the ’94 Italian Grand Prix.

Mika Salo and Alessandro Zanardi were the intended drivers, but the team were forced to pull the garage door down for good in January ’95 in the face of mounting debts, leaving the 112 a stillborn project.

Honda RA009

Jos Verstappen in the Honda RA099 – the project was halted after Harvey Postlethwaite’s death

Grand Prix Photo

After Harvey Postlethwaite left Tyrrell, he was contracted to mastermind the fledgling Honda works project, slated for a 2000 entry into F1.

Postlethwaite designed a testing mule, the RA009, intended as a precursor to the full-blown 2000 car.

The ‘Honda’ was built by Dallara and Jos Verstappen was hired as the test driver, pounding round Jerez and setting times which would have comfortably put them in the ’99 midfield.

However, Postlethwaite tragically died of a heart attack whilst the team were testing in Spain, and the project lost its momentum.

The full team idea was canned, and Honda moved into supplying works engines to BAR and Jordan in 2000 instead.