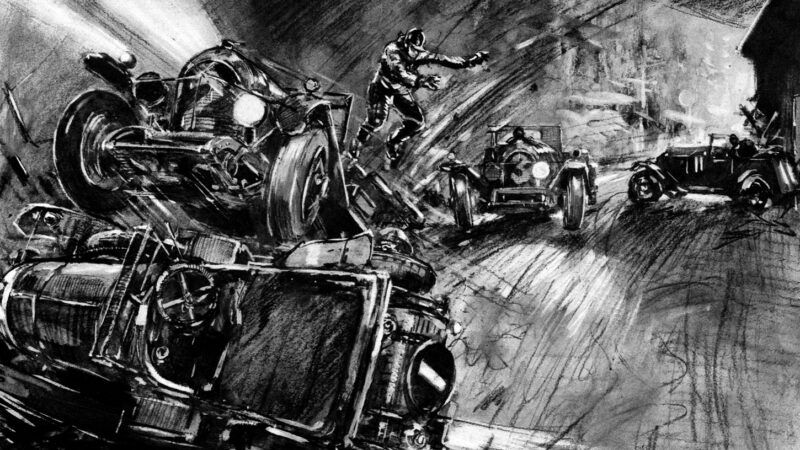

“The danger… the never-say-die determination”

The victory party is held at the Savoy, hosted by The Autocar. And when Sir Edward Iliffe stands up to speak he begins, “I feel there is someone missing here this evening who ought to be present.” At which moment an engine fires up and a very battered Bentley drives into the room. Everyone goes nuts.

It’s all there: the danger, the victory against impossible odds and, of course, the talent, never-say-die determination and courage of those involved. The ‘Bentley Boys’.

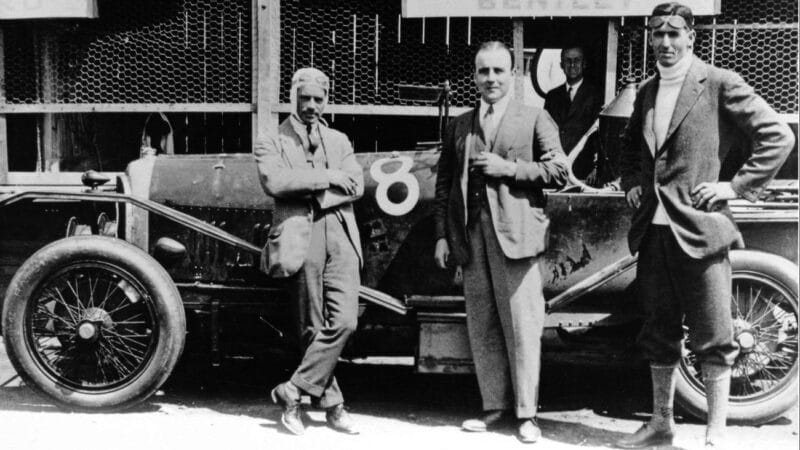

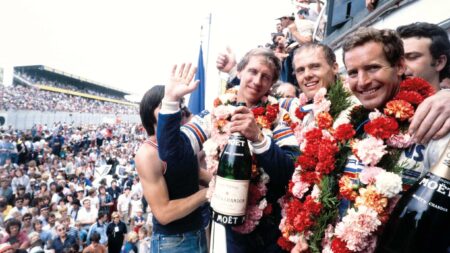

The Bentley Boys stand proud in 1929, oil and grime-stained

Brietling

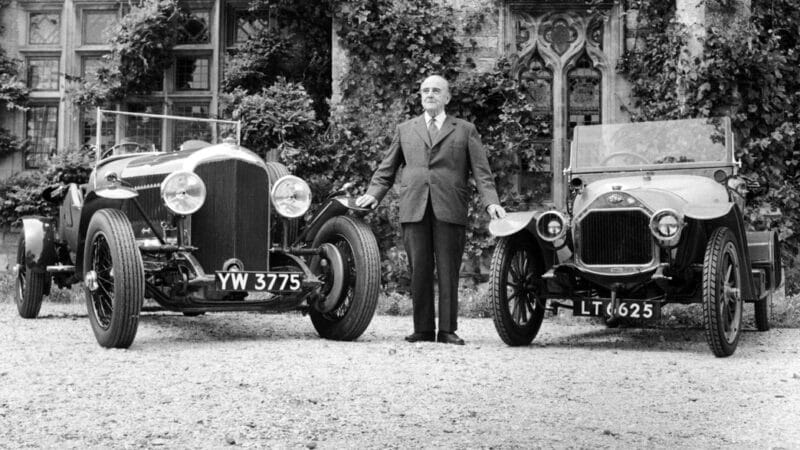

But Davis and Benjafield were not the first. Hell, they weren’t even the first to win Le Mans in a Bentley. The first Bentley boy was John Duff, the man who entered his 3-litre into the first Le Mans, much to the chagrin of WO Bentley himself, who reckoned not a single car would finish. A Canadian who’d been terribly injured at Passchendaele, among his many pre-Le Mans automotive feats was to set a load of 24 hour class records in his Bentley at Brooklands on 1922. He drove two 12-hour stints, sitting on a bare aluminium bucket seat too short for his tall frame, leaving his back in such terrible condition that after the first 12 hours he had to be lifted from the car and helped into the bath. The following morning he was back in the car to capture 39 speed records including a new 24-hour record at almost 87mph.

When Duff entered Le Mans, WO relented at the last moment and went to France to man the pits. The Bentley was the quickest car in the race, but poorly prepared for the rutted, dusty roads that made up the track. When a stone holed the fuel tank, Duff had no choice but to run four miles to the pits, alert team-mate Frank Clement (the only professional racing driver WO ever hired) who took a bicycle – there’s a story he stole it from a gendarme I hope is true – and rode back up the track, against the flow of traffic to mend the car and resume the race. “It was absolutely terrifying,” he would later remember, “I thought they were going to mow me down every minute.” Quite.