Top Le Mans moments 50-41: from Bentley's begrudging entry to Porsche's perfect ad

Another ten dramatic tales from a century of the Le Mans 24 Hours include the first 250 km/h lap, Rondeau’s victory in a Rondeau, and a win allegedly fuelled by double brandies

Getty Images

50 – 1923 W.O. Bentley sees the light

It’s hard to calculate exactly how much Bentley did for Le Mans during its formative years. Had the British team never arrived to test its mettle (and metal) against a near-exclusively French entry, the event might not have caught on.

Yet the British very nearly didn’t turn up, and if W.O. Bentley had had his way, they wouldn’t have. Forever cash-strapped but also forever chasing a sales hook, W.O. took a gamble in 1922 by shipping a car off to the Indy 500. Driver Douglas Hawkes qualified almost 20mph off the pace and finished 13th. W.O. concluded that his cars “simply weren’t fast enough”. This was hardly the return he’d desired from an expensive transatlantic trip.

So he was less than enthused when war veteran Captain John Duff approached him with the idea of taking a car to Europe for the first time to have a crack at this new day-long endurance race. Duff was no stranger to W.O. having already embarked on several record exploits – including raising the speed record for driving for 24 hours at Brooklands in 1922 (even if his effort was split into two 12-hour stints so locals could get a night’s sleep).

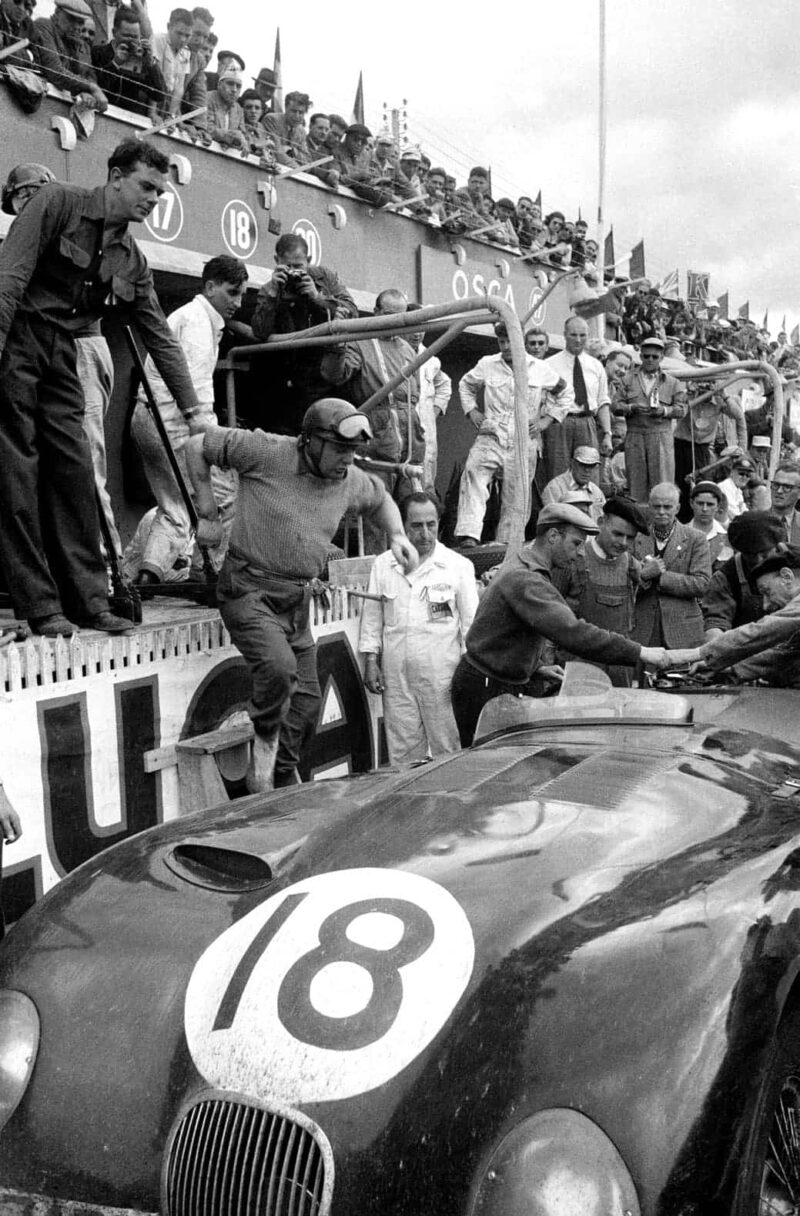

Bentley in the pits in 1923, despite the fact W.O. never actually wanted it there. Thank you, Captain Duff!

Getty Images

W.O. wanted no part of this Grand Prix d’Endurance, but agreed to sell Duff a 3-Litre Sport and loan test driver Frank Clement. The pair stuffed what meagre spares they could into the chassis, along with two Bentley mechanics, and headed off to La Sarthe.

Then at the last moment W.O. changed his mind and set off to France to see how his ramshackle team would get on. Upon arrival, he found an entry of 35 cars and was treated to a highly respectable display by his crew. Forget the Indianapolis disappointment, Bentley could have won the first Le Mans.

The 3-Litre Sport went toe-to-toe with the Chenard et Walcker of André Lagache/René Léonard, only losing time when a stone flicked up from the pitted road and smashed a headlight. Eventually Bentley’s challenge ended when the car stopped at Arnage at midday on Sunday, its fuel tank punctured by another errant stone. It would take over two hours for Clement to exact repairs and get going again (see #49). But it had done enough to convince W.O. that this race was one worth winning: “By midnight, I was certain that this was the greatest race I had ever seen,” he said.

49 – 1923 Frank Clement cycles against the flow

It had all been going so well. With the sun up, Bentley was gaining with each passing hour. Frank Clement and John Duff were flying, having earned back one of the laps they’d lost to the Chenard et Walcker through the night. Then, disaster. Clement ran dry of fuel at Arnage, and a quick peek under the car revealed the cause, a stone had punctured the fuel tank.

Riding to the rescue: Frank Clement borrowed a police pushbike to keep Bentley on track

Getty Images

As quick thinking as he was driving, Clement convinced a gendarme to loan him his bicycle, and set off back to the pits. He retrieved a cork, slung two jerry cans of fuel over his shoulders and returned, cycling the wrong way round the circuit, against the race traffic. “It was absolutely terrifying,” Clement would later recall. “I thought they would mow me down every minute!” Clement completed the trip, bunged and topped the tank and rejoined, the car taking the finish in fourth.

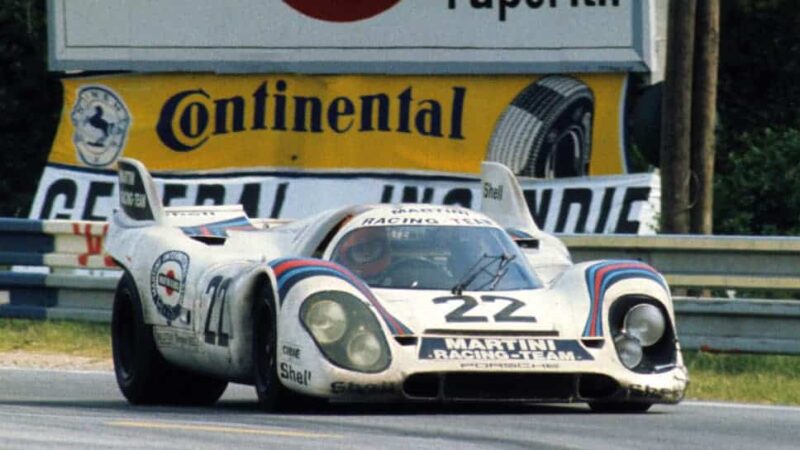

48 – 1971 Oliver clocks first 250km/h lap

The 5-litre engine’s swansong made 1971 was significant. Jackie Oliver set the first ever 250km/h (155mph) lap at the Test Day in his Porsche 917, peaking at over 385km/h (240mph) on the Mulsanne, and the race was run at a pace that set a record distance – which stood for nearly four decades. No chicanes and good weather allowed a flying run for Gijs van Lennep and future Red Bull driver boss Helmut Marko to take Porsche’s second consecutive win, clocking more than 5000 miles in the process.

Martini cocktail of Marko/van Lennep and Porsche’s 917 left a hangover that lasted nearly 40 years

DPPI

47 – 1933 Nuvolari’s special one-off

Tazio Nuvolari only raced at Le Mans once, but it was all it took. Driving a factory supplied 2.3-litre supercharged Alfa Romeo 8C partnered with the brilliant Raymond Sommer who’d driven 22 hours to win the race (almost) solo the year before, it was a Le Mans dream team of Ickx/Bell proportions. They took turns in breaking the lap record and despite myriad problems dogging their performance, still won. Nuvolari’s Le Mans record of played one, won one puts him with the likes of Woolf Barnato, Nico Hülkenberg and Fernando Alonso as one of just eight drivers with unbeaten records at Le Mans.

46 – 2012 A hybrid wins (or does it?)

Six years after the turbodiesel revolution, Audi introduced hybrid technology to sports car racing, via a flywheel accumulator system developed by Williams Advanced Engineering. But at Le Mans, fearing unreliability, the manufacturer hedged its bets, running two hybrid R18 e-tron quattros and two without the system. Even the hybrid cars were designed to run without the electric power – which was just as well for the winning car that apparently made more landmark history for Audi. “Our hybrid went one hour into the race and yet we still won,” says engineer Leena Gade. “Some of the other competitors knew. The system was tough to work with and there were issues.”

45 – 1980 Quirky Rondeau sends France into rapture

Factory teams took a breather – and frankly the quality of entry slumped as the decade turned. But let’s look on the bright side. Local hero Jean Rondeau still had to fend off legions of Porsche 935s and Jacky Ickx and Reinhold Joest in the 908/80 when he claimed victory in his eponymous M379B. Rondeau and team-mate Jean-Pierre Jaussaud negotiated race-long rain and fog in what would turn out to be a classic race – the only time a driver has won with a car bearing their own name.

44 – 1930 Barnato’s perfect hat-trick

This wealthy amateur with a professional outlook was coached by the best and trained hard: for a wide variety of sports. He arrived late to motor racing, but did so fit, concentrated and imbued with a team ethic. Fast and consistent, one had to get up early – and drive through the night – to beat him. Three attempts, three different co-drivers and three wins: an unrepeated feat. Oh, and he was the chairman – and the money behind – the Bentley company that he drove for.

43 – 1953 Hamilton orders the double brandies (allegedly)

It’s one of the great stories, and told first hand, too. In Duncan Hamilton’s autobiography he describes how, having been slung out of the race in practice, he and his Jaguar team-mate Tony Rolt indulged in “a night of steady imbibing” during which “Tony and I never saw our bedroom.” He said they were found in something of a state at 10am on Saturday morning by William Lyons who told them they were back in the race. By 2pm, two hours before the flag fell and after several black coffees and a Turkish bath, both still felt dreadful. Double brandies were ordered which did the trick, off they toddled and won the race.

Sloshed the night before or not, the story shouldn’t cloud a superb Jaguar performance

Getty Images

As a racing story of derring-do to thrill the heart, it could only have been materially improved by being true, which, sadly, it was not. Yes, they’d been excluded but Jaguar had immediately appealed the decision and the outcome of that still hung in the balance while Duncan and Tony were allegedly getting quietly sozzled. We’re not saying they didn’t have a drink, but an all-night binge with still the possibility of doing a 24-hour race the next day? Really? Sadly the story has continued to obscure what did actually happen to this day – a fine win and the first at Le Mans by a car using disc brakes.

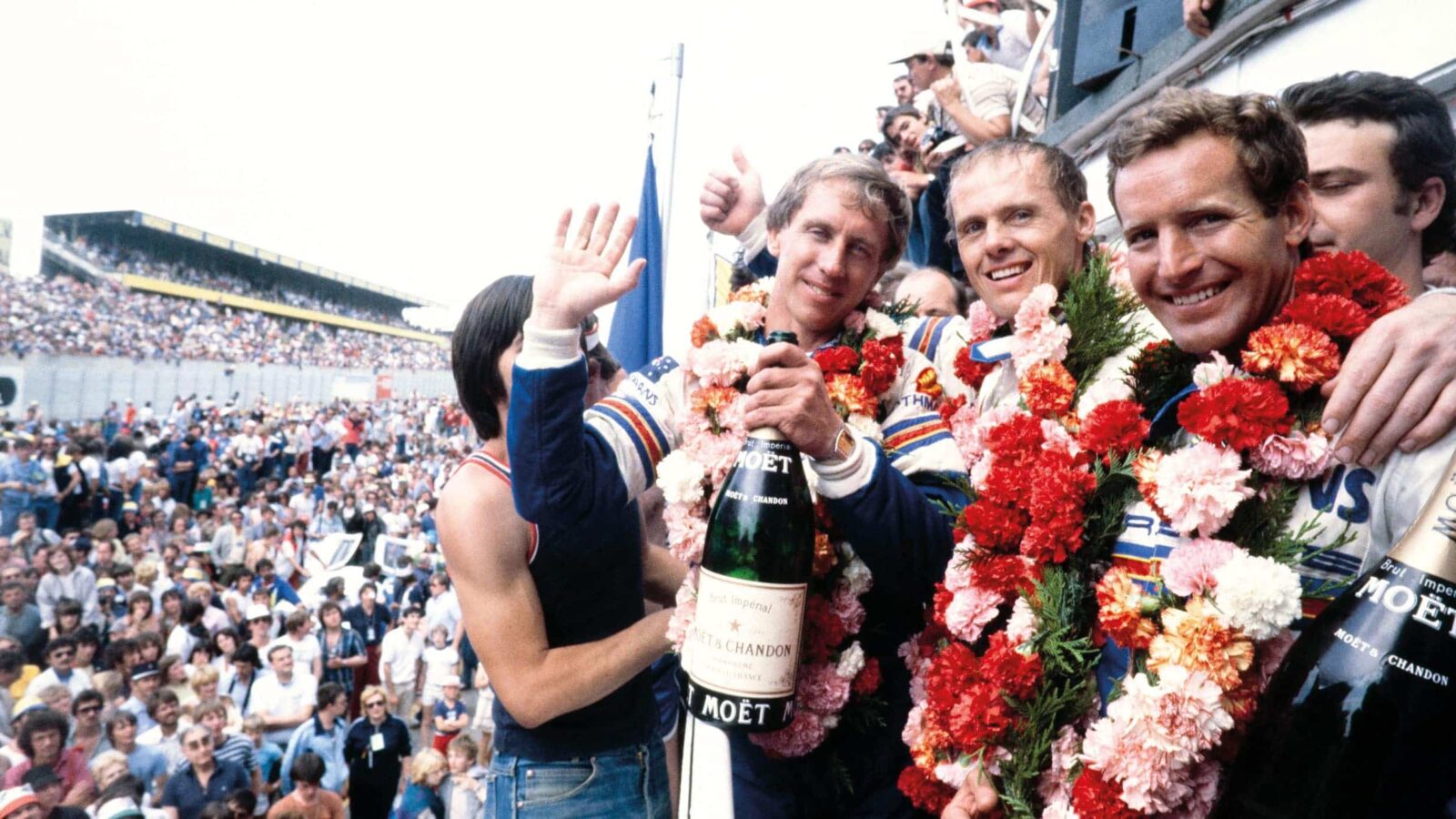

42 – 1983 Holbert coaxes it home

“We had led for 21 hours,” says Vern Schuppan, co-driver to Al Holbert and Hurley Haywood in a works Porsche 956. “I was driving when the left-hand door blew off: like an explosion – at max speed just after the Mulsanne Kink. I stayed out until I got black-flagged. That allowed the team to ready a door. They slapped it on and riveted aluminium strips to it at the front and to the roof.

“I got black-flagged again: a driver had to be able to open the door. They punched a hole in the roof and fastened it with a leather strap that I could unbuckle. But the door didn’t fit well and some airflow was being diverted from the intercooler.

The moment everybody held their breath, but Al Holbert kept his cool and kept the Porsche rolling to victory

Getty Images

“I handed over to Al with about half an hour to go and warned about the rising temperature. About 10 minutes from the end I was standing with Hurley watching a TV screen. S**t! Smoke. Left-hand bank!

“It was good that Al was in there. He had a lot of empathy for the car. On the last lap, [exiting the Ford chicane] the motor actually stopped – but he dropped the clutch and it freed.”

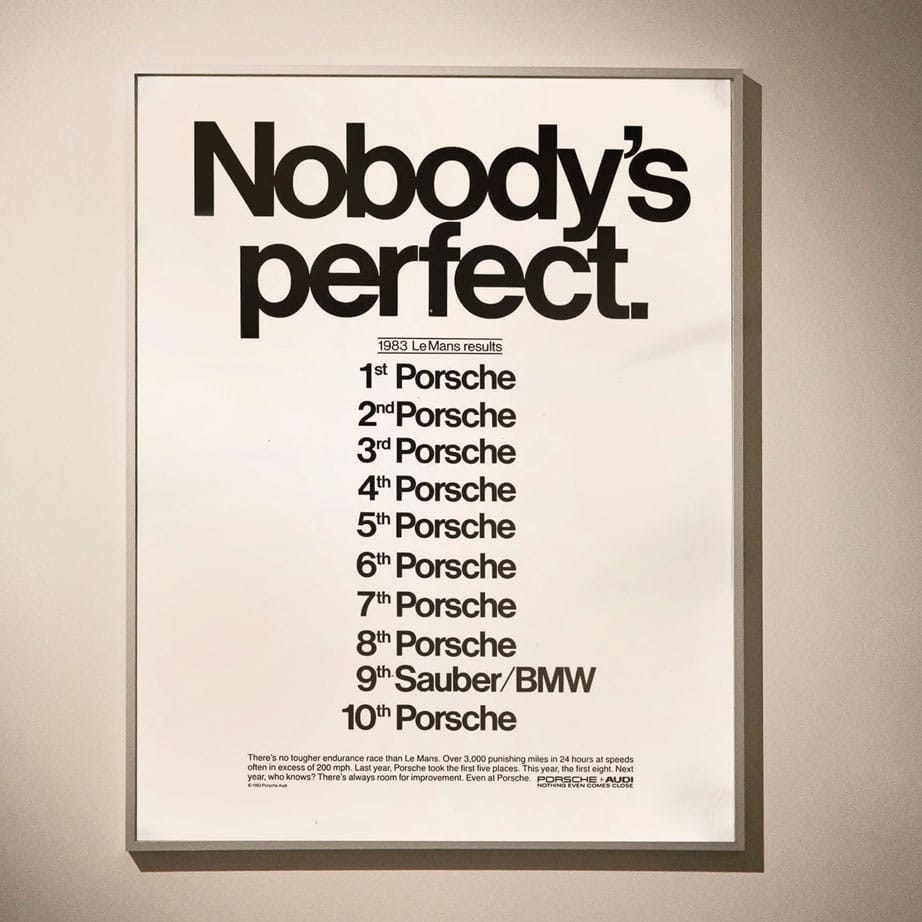

41 – 1983 The best bit of marketing

Win on Sunday, sell on Monday? That old cliché is still at the heart of why manufacturers go motor racing. But once the race is won, spreading the word is an art in itself. Porsche’s ad following its domination in 1983 showed the way just as the 956 had so comprehensively in the race. Nobody’s perfect? You can’t beat a droll bit of humour to underline your point.