Top Le Mans moments 60-51: Alonso wins after quadruple sprint & Newman shines

Our Le Mans at 100 countdown reaches the halfway point with Fernando Alonso’s committed winning drive, a change to the track layout, and Birkin vs Caracciola

Mercedes’ master Caracciola only got one go at Le Mans, and it ended too soon

Getty Images

60 – 2018 Alonso’s star quintuple stint

Footage of the safety car restarts proved how much Fernando Alonso wanted a Le Mans victory on his CV. He was nigh on four wheels off on the high-speed run from Mulsanne Corner to Indianapolis on at least one occasion.

The Spaniard, in what was presumed to be the twilight of his career, had set out to secure his legacy by completing the unofficial Triple Crown of motor sport with the addition of Indy 500 and Le Mans victories to his Monaco Grand Prix double in 2006-07. He’d been in the mix to drive for Porsche in 2015 in the berth that went to Nico Hülkenberg, only for McLaren engine supplier Honda to veto the plan. But after making his Indy debut in 2017, he got a chance to race at Le Mans for the first time as part of Toyota’s assault on the 2018-19 World Endurance Championship super-season.

Alonso took the opportunity with both hands. He was aboard the Toyota TS050 Hybrid shared with Sébastien Buemi and Kazuki Nakajima during the defining period of the race in the small hours on Sunday morning. A quadruple stint turned into a quintuple and victory was all but secured.

No one-trick pony: Fernando Alonso celebrates the first of his two Le Mans wins in 2018

Getty Images

59 – 1999 Toyota tyre blowout confirms BMW’s win

This year is remembered for the hat-trick of harrowing Mercedes flips (see #12), but it was another German manufacturer that sealed victory at only its second top-class attempt. Utilising superior fuel economy, BMW’s Williams F1 team-developed V12 LMR inherited the win after the sister car crashed out and the faster Toyota GT-Ones hit trouble (including a punted shunt for Thierry Boutsen that ended his career). The result made Yannick Dalmas a four-time winner. BMW hasn’t challenged for the overall win since, but an LMDh attack in 2024 might change that.

58 – 1972 Major track change enhances the challenge

Plans for a permanent Mulsanne Straight never reached fruition, but the shape of the Circuit de la Sarthe still changed forever – and we’d say for the better. A sweeping section of permanent track replaced the difficult and dangerous Maison Blanche, with a second chicane added to Virage Ford to accommodate a new pitlane entry. The work was financed by Porsche – hence the birth of the glorious Porsche Curves.

57 – 1996 Joest makes a Porsche out of a Jaguar

The Porsche WSC95 started life as a 1991 Jaguar XJR-14, converted in 1994 by TWR on Porsche’s instruction into an IMSA-eligible, Porsche-powered open racer. But when IMSA tweaked the rules to slow the car before Daytona, Porsche pulled the plug. Joest rented the car for Le Mans in 1996 and promptly won. Part of the deal was that Reinhold Joest could keep the car if it did, so he entered it again in 1997 – and won again, to beat the factory twice in succession.

56 – 1984 Jaguar returns to Le Mans

About time. Jaguar returned to its spiritual sporting home 27 years after its last victory, but it would not be a happy reunion. The US-based Group 44 team brought its XJR-5s to La Sarthe, but the regular IMSA race winner struggled to stretch its legs at Le Mans – both entries failed to finish. It was a sobering return. But amid XJ-S glory in the European Touring Car Championship, a new partnership with TWR was soon brewing that would result in the potent XJR-6. Tom Walkinshaw was nearly ready to pounce.

55 – 1965 Ferrari’s phantom third driver

Ferrari’s last overall win: Masten Gregory, young firebrand Jochen Rindt, North American Racing Team (NART) and its 250LM. But did American Ed Hugus relieve the visually impaired Gregory for a brief stint during the night because the Kansas City Flash was spooked by the dark? The claim from the reserve driver only emerged in the late 1990s, long after the major players had died – and the evidence is stacked against it. But Ferrari’s phantom third driver remains Le Mans’ most intriguing mystery.

54 – 1930 Birkin and Caracciola face off

The relationship between W.O. Bentley, Woolf Barnato and Henry ‘Tim’ Birkin was complicated. W.O. detested Birkin’s bolting of a Roots blower to his 4.4-litre ‘four’, while money man Barnato partly funded the build of the required 50 such cars.

The smallest field in the race’s history packed a hefty punch. Rudi Caracciola’s supercharged 7.1-litre Mercedes-Benz was the first German car to take the start – and it led by 18sec at the end of the first lap. Its driver-operated blower needed to be employed sparingly such was its effect on mpg, and so Bentley was expected to use its numerical superiority – three naturally aspirated 6.6-litre Speed Six and a couple of ‘Blowers’ – to keep the pressure up. Birkin fired its first and most memorable salvo. On lap four, with canvas breaker showing through a rear tread and two wheels on the grass, he passed Caracciola at an estimated 126mph – and broke the lap record. Though regular tyre failures blighted his progress thereafter, he had set the tone.

The lone Merc didn’t crumble – it lasted until its battery died at mid-distance – but the surviving Speed Six would finish 1-2.

Barnato and Glen Kidston’s winning Bentley

53 – 2006 Audi’s diesel revolution

Bar talk. That’s all it was at first. Yet five years later Audi brought a diesel engine to Le Mans and broke every old perception about so-called oil-burners. But the whispering 5.5-litre V12 turbodiesel in the back of the R10 TDI that dominated on its Le Mans debut was far from trouble-free. A complex injector problem haunted the team into the race and helped delay one car. Yet the other, driven by Emanuele Pirro, Frank Biela and Marco Werner, finished four laps ahead of the Judd-engined next-best from Pescarolo. Astonishing.

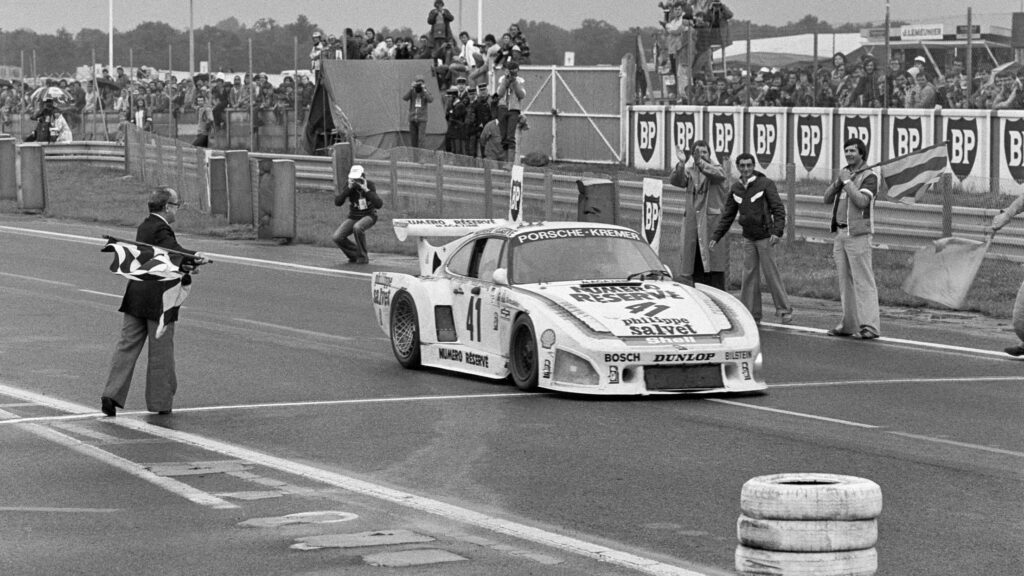

52 – 1979 Bill Whittington saves Kremer’s day

In hindsight, Group C couldn’t come soon enough amid fractured rules and manufacturer apathy. In the meantime, two sets of brothers made hay. The Kremers’ heavily-modified K3 version of the 935 dominated once the Group 6 cars hit trouble, US siblings Don and Bill Whittington – sharing with Klaus Ludwig – finding themselves at dawn on Sunday with a 12-lap lead. But at 11am Bill stopped on the Mulsanne when a drivebelt jumped off the fuel injector pump. He lost 79 minutes before his Heath Robinson fix using a spare alternator belt got him back to the pits. A further 15 minutes were lost to repairs – but they got lucky as the rival Barbour 935 hit pit trouble with a stuck wheel. Ludwig won Le Mans twice more, again for a Porsche customer (Joest), while the Whittingtons headed for… infamy via criminal convictions for money laundering, tax evasion and drug smuggling!

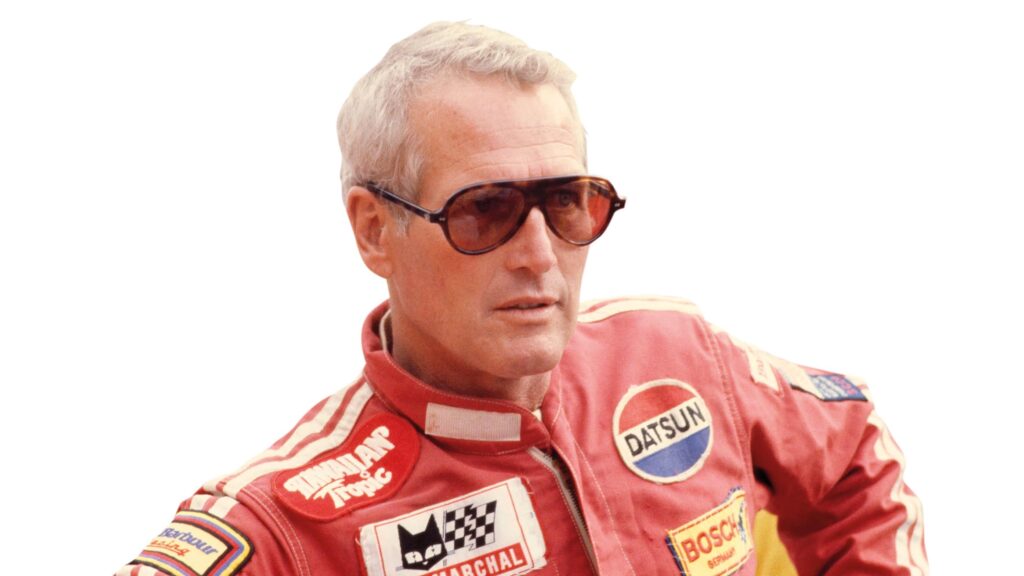

51 – 1979 Newman shines

Steve McQueen made the movie, but Paul Newman did it for real. Rolf Stommelen was the ace that delivered Dick Barbour and Newman second place. But Newman hated the frenzy of attention and never came back. Meanwhile, some bloke from Pink Floyd took a Lola T297 to second in class. “The press didn’t care about some old drummer,” says Nick Mason, happily.