Lunch with Jochen Mass

Not many racing drivers have mixed competing in grands prix with sailing trips across the Atlantic. And that’s before you factor in this laid-back German’s sports car successes

Getty Images

For most of 2009, a quarter of the drivers on the grand prix grid were from Germany. And, thanks to the long reign of Michael Schumacher, that country is statistically one of the more successful in Formula 1’s history. Yet, in the first two decades of F1, the only German front-runner was Wolfgang von Trips, whose career ended tragically at Monza in 1961.

Then, in the early 1970s, a brilliant young protégé of Ford of Cologne started to attract attention, and was soon being tipped as a future world champion. But it didn’t turn out quite like that for Jochen Mass. His highly successful racing career lasted through three decades; but, out of 105 grands prix, his only victory was in the accident-shortened Barcelona race in 1975. Today he’s relaxed about that. He lives a busy life indulging his wide-ranging interests, from the development of wind-powered nautical freighters to the writings of the Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu. Maybe that broad-minded approach to life got in the way of reaching the top of the motor racing tree, for Jochen was never a man to take things too seriously, and his laid-back, good-humoured approach was maybe out of synch with the way motor racing was already going in the ’70s. Had he been a grand prix driver in the 1930s, or even the ’50s, he would have fitted in perfectly. But the speed, and the racing intelligence, was always there.

For more than 20 years Jochen and his beautiful wife Bettina have lived in the South of France, half an hour’s drive from the beach and, in the winter, an hour from good skiing. Their rustic cottage perches high above the gorge of the Loup river, with awe-inspiring views along the silent valley. His favourite ride, an ancient Harley now on its third engine, is in the shed. On the terrace, overhung with vines which filter the warm October sun, Bettina serves tomato salad heaped on French bread rubbed with garlic, a little pasta, tender fillet steak with sliced ratatouille, local goats’ cheese and iced coffee, helped along by a Provençal rosé. Having lived in Germany, England, South Africa and France, Jochen is a polyglot: he speaks German to Bettina (who is half-American), English to his kids and French to the locals, and reads all three with equal facility.

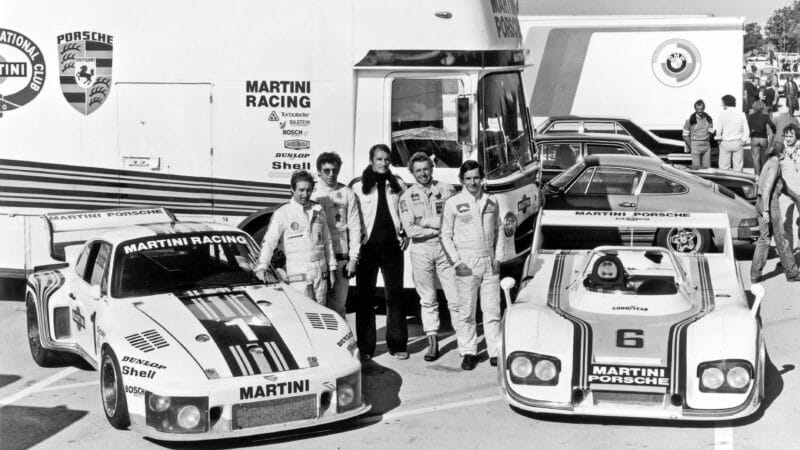

After a sailing life, Mass discovered racing and got his big break with Ford, first in hillclimbs, and then in touring car Capris

Motorsport Images

He was born near Munich in 1946, into the bleakness of immediate post-war Germany. When he was eight his father died. “There was no money, and my mother had to work hard to keep my sister and me. My father came from a sea-faring family, and the sea fascinated me. The doodles in the margins of my schoolbooks were always ships. As soon as I could get away from school, I went into the merchant navy. At 17 I went by banana boat to South America, then I went to Africa, Scandinavia and Russia: the White Sea, Archangel in winter. It was tough, but every day was exciting. It had a huge positive influence on me.

“I got a job in a bank, but after life at sea that was just rubbish”

“But after three hard years it was time to come home. Container ships were taking over, and the appeal wasn’t the same any more. I got a job in a bank for a few months, but after life at sea that was just rubbish. One day, at a girlfriend’s suggestion, I went along to a local hillclimb. When I was a kid motor racing only got into the newspapers when there were accidents – Le Mans 1955, the Mille Miglia 1957 – so I associated it with disaster and death. But that hillclimb connected with three of my senses: sight, noise, smell. It clicked. The Alfa dealer in Mannheim did some racing, so I quit the bank with relief and got a job there as a mechanic. It took me a year to talk him into letting me drive in a local hillclimb. In a standard Giulia saloon, I came second behind a race-prepared car. In 1968, when I was 21, I did my first circuit race on an airfield at Ulm in one of the dealer’s GTAs, and won my class. I just seemed to take to it: natural ability, I suppose. You either have it, or you don’t. I was doing well against Gerd Schüler, Ford’s hillclimb man with a works Escort, so when Ford had a big test at Zandvoort they invited me. There were 30 drivers there, established racers like Tim Schenken and Howden Ganley, Jean-Pierre Jabouille and Jean-François Piot, and they gave each of us five laps. The four fastest were covered by a fifth of a second: Dieter Glemser and Manfred Mohr, who already had Ford contracts, and Helmut Marko and me.

All smiles in 1974 among a famous crowd: Carlos Pace, Niki Lauda, Mass and Emerson Fittipaldi

“After that Ford summoned me to Cologne and offered me a contract. They said, ‘What do you want to earn?’ As a mechanic I was earning 50 pfennigs an hour, and my mother made me a little bread roll for my lunch. With overtime I ended up with about 1800 marks a year. I didn’t have the faintest idea what a racing driver got paid. Whatever I said, it would be too little, or too much. So I just gaped at them, and they smirked back at me. Then they said, ‘OK, we’ll give you 70,000 marks a year, plus expenses and a company car.’ I couldn’t believe my ears!

“At first they ran me in V6 Capris in the European Championship hillclimbs – long mountain passes like Mont Ventoux, Trento Bondone, Mont Dore, Dobratsch. Hilariously dangerous, and a real adrenaline rush. I loved hillclimbs because it was what I’d been doing, flat out from the word go. By 1971 I was on the circuits in Capris, and I won the German Touring Car Championship. I’d never sat in a single-seater, not even in a kart, but in 1971 a friend lined up a SuperVee for me. I won at Thruxton on Easter Monday, and the German GP support at the Nürburgring. Then Jochen Neerpasch of Ford told me to get myself to England, because they’d got me a Formula 3 Brabham.

“I towed it around the UK behind a Ford Transit, with a huge Danish mechanic called Gunnar, a really good guy, like a big faithful dog. I called him my Great Dane. We did the last half-dozen rounds of the British championship, up against Jody Scheckter, James Hunt, Roger Williamson, Dave Walker. I got some good places, and I won at Castle Combe after a big battle with Jody. That put me on the map.”

Mass joined McLaren full-time for 1975 and guided his M23-Ford to his one and only grand prix win at Montjuich Park.

In 1972 Jochen really hit the headlines. March put him in Ronnie Peterson’s works Formula 2 car when Ronnie was otherwise engaged, and he led his first F2 race, the Jim Clark Trophy at Hockenheim, until his clutch went. Two weeks later he won his second, the Eifelrennen at the Nürburgring. For Ford Cologne he was crowned European Touring Car Champion, with outright wins in the 2.6 Capris in the Spa 24 Hours, the Silverstone TT, Monza, Zandvoort and Jarama. The Capris also did Le Mans that year. “I hated it with a passion, because we were doing it in a bloody touring car, all the time trying to get out of the way of the fastest sports prototypes. That was the year Jo Bonnier was killed, after he collided with a slower car.”

In fact Jochen and co-driver Hans Stuck qualified 30th out of 55 starters, and were in a class-leading 15th place at dawn when the engine threw a rod.

“I hated Le Mans with a passion because we were in a bloody touring car”

He kept on with F3 with a works March, and sampled Monaco for the first time. “Out of 70 entries, the best 40 qualified for the heats, and the top 10 in each heat went into the final. On the last lap of my heat I was only 12th, and I just had to make the final. The guy in front of me thought the same, he moved out to overtake, I hit his back wheel, flew over him and the man in front of him, bent the suspension when I landed, and crossed the line 10th. So I was in, on the back row, and it was raining hard. I passed eight cars on the first lap, and I’d got up to fifth when a couple of cars tangled in front of me at Mirabeau. I had to stop dead, and then one of them selected reverse and ran over my nose cone. In the end I finished seventh.

“My best F3 race was at the ’Ring. It was teeming with rain, and off the line I got water in the electrics and chugged away on three cylinders. Everybody came steaming past me, then number four chimed in, and I went past them all on the outside and found myself in the lead. The whole of the Nordschleife, empty in front of me. At Brünnchen there was a river running across the road, and I aquaplaned off and spun. I expected the rest to come pouring over the brow, but they didn’t, and I got going again and won. Patrick Depailler’s Alpine was second.”

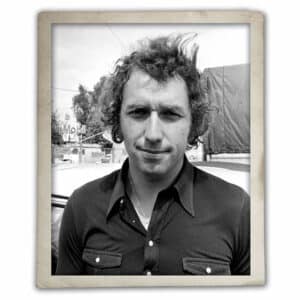

Alongside ‘golden boy’ James Hunt

Getty Images

Jochen raced sports cars, too, sharing a works Chevron with Gerry Birrell in the Springbok Series. They were second overall in the Kyalami Nine Hours behind the Regazzoni/Merzario Ferrari 312P, and Jochen won at Cape Town, Lourenço Marques and Pietermaritzburg. “At Kyalami the front row of the grid was two Ferrari 312Ps – Clay Regazzoni on pole, Jacky Ickx next to him – and me in the Chevron. As they cleared the grid I suddenly realised I didn’t know where the starter was. I looked around frantically, couldn’t see him, then I thought Jacky will know, and I looked across at him. He was looking around frantically too. At that moment the flag must have fallen, because Regga took off, leaving me and Jacky standing.”

For 1973 Jochen had a full F2 drive for Surtees. “John’s F2 cars were very good. I won two rounds and finished second in the European Championship, even though we had the Ford engine when the BMW was the one to have.” At Rouen his friend Birrell was killed. “We raced together in the Springbok Series and in the Capris, we travelled together. He was very talented. In practice I had a problem and stopped beside the track. Gerry came past slowly, cooling his tyres before going for a fast lap, and waved to me. Then practice was red-flagged, I didn’t know why. I was towed back to the paddock, and John told me Gerry was dead. It was a dreadful shock. His wife Margaret had just given birth to twin daughters.”

The front-left tyre of Birrell’s Chevron had punctured on the 155mph downhill stretch, and he hit the Armco head-on – Armco that the drivers had already complained was poorly fixed. The barrier lifted on impact and the car went underneath. Birrell’s death looms large in Jochen’s memory, and he forgets to mention that he had to start the final on the back row. In five laps he climbed from 18th to fourth place, and went on to finish second. Three weeks later Surtees gave Jochen his first F1 ride, in the British Grand Prix, but the first-lap pile-up took him out. So his first proper F1 race was the German GP, on his beloved Nürburgring. Having passed five cars on the first lap he finished seventh, in a frantic sandwich between Emerson Fittipaldi’s Lotus and Jackie Oliver’s Shadow.

Meanwhile, Ford was taking the European Touring Car rounds very seriously: for the 1973 Nürburgring Six Hours it added world champions Jackie Stewart and Emerson Fittipaldi to the line-up, while BMW had Niki Lauda and Chris Amon joining Hans Stuck. “In practice I was slightly quicker than Jackie, so he asked me to try his car to see if it was OK. I did, and beat his time, so he said, ‘Fine, it must be me then,’ jumped in and went quicker. But I managed to stay ahead of him by a little bit. Emerson wasn’t so happy in the Capri and was a fair bit slower.” In the race Mass led the early stages from Lauda, Stuck and Stewart. His co-driver Dieter Glemser later crashed heavily, so he took over another Capri, but was clouted by a back-marker and ended up on his roof. Amon/Stuck won.

Mass aboard a Porsche 936

During 1973 Jochen’s Surtees F2 team-mate Mike Hailwood showed him a photograph of an old ocean-going sailing ship. “A top-sail schooner, 128 feet, built in 1919. It reawakened all my old love of the sea. Mike had just bought it, and he wanted me and some others to come in with him. I had to say yes. Then, predictably, Mike and the others all dropped out, so it ended up mine. Gradually I got it all perfect, and I sailed it everywhere, across the Atlantic, Africa, down to South America. I had it for nearly 20 years – until a professional I’d left it with while I was away racing wrecked it on a sandbank on the north German coast. It was a total loss.”

For 1974 Jochen was a fully-fledged F1 driver for Surtees, alongside Carlos Pace. It was a disaster. “John was operating on a shoestring budget. The sponsors, Bang & Olufsen hi-fi, hardly ever paid, and we had a lot of breakages, retired everywhere. At Monaco something fell off in each practice session, and the last straw was when a rear upright broke. I said to John, ‘You can drive it yourself tomorrow, because I’m not going to.’ Actually I’d qualified quicker than Carlos, but out of principle it felt wrong. For a young guy at the start of his F1 career to refuse to drive at Monaco was a big decision, and I didn’t sleep much that night. The BBC said I’d walked out of the team, so John made a press statement saying I was under contract, with two more years to run. That just wasn’t true. I went down to Edenbridge and John showed me my contract, which had some additions in different ink. John said, ‘That’s what you signed.’ I said, ‘John, you and I both know that’s not true. Unless you give me a letter to say that’s not how I am contracted, I’m walking.’”

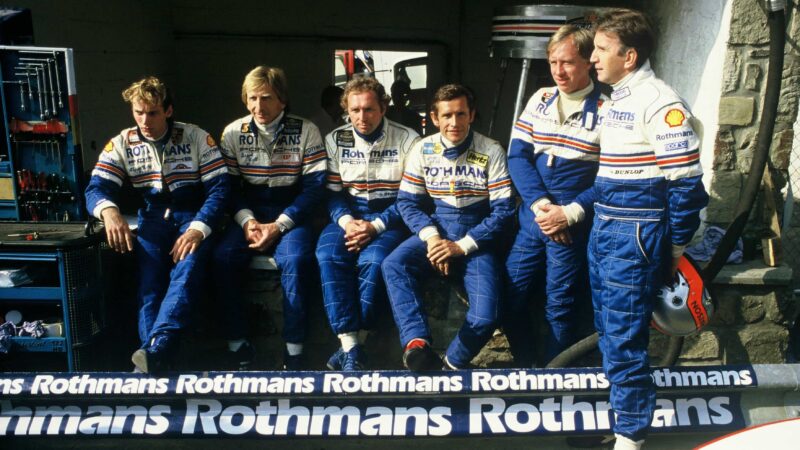

Mass, Reuter and Dickens after their Le Mans win in 1989

Getty Images

A letter duly appeared, but the front suspension broke next time out in Sweden. In France it was a CV joint, by which time an unhappy Pace had left the team. At Brands Hatch Jochen was fast down the straights and slow in the corners. “I didn’t have enough downforce. John had changed the car without telling me. He always decided things like that, he always knew better. That’s when I decided to break my contract and leave. Also, he hadn’t paid me anything, owed me £30,000, a lot of money then. But Ford Germany twisted my arm, they said, ‘You can’t leave just before the German GP.’ So I went to the Nürburgring, started tenth, and I was fourth at the end of the first lap behind Regazzoni, Scheckter and Reutemann. I was still fourth when the engine blew. Then I left.

“Of course going to Surtees was bad for my career, and I had my difficulties with him, but somehow I always respected him, and I had sympathy for his predicament. And now Henry’s death is so dreadful. I spent time with them both at the Festival of Speed last July, chatting and joking around. Henry was clearly very talented, he was going to go a long way, and he was such a nice kid. It is an unimaginable tragedy for John and his family, a cruel freakish accident.”

In that 1974 German GP Mike Hailwood, in the third McLaren which ran in Yardley colours, crashed heavily, shattering his right leg. It was the end of Mike’s car racing career, although he was to make a brilliant motorcycle TT comeback four years later. So for the last two GPs of the season Jochen drove the Yardley M23, and for 1975 he had a proper McLaren deal, number two to world champion Emerson Fittipaldi.

“They put a piece of tape over the Gurney flap, and that was worth 1.5 seconds”

“Emerson and I got on very well. He always kept his cards close to his chest – but that’s normal in F1. He was a bloody fantastic driver, but some circuits didn’t suit him so well, and I out-qualified him at Ricard and the Nürburgring.” Jochen was third at Interlagos, Paul Ricard and Watkins Glen. At the Spanish GP, with the Montjuich Park road circuit surrounded by loose and inadequate Armco, most of the drivers boycotted practice, and Fittipaldi refused to race. Rolf Stommelen crashed into the crowd, killing four spectators: Jochen, leading when the race was abandoned, took no pleasure from what was to prove his only F1 victory.

F1 didn’t work out, but Mass was at home with Porsche in sports cars

His Ford touring car deal continued through 1975, and in sports cars he drove for Alfa Romeo, sharing with Scheckter to lead the Nürburgring 1000Kms and winning at Enna with Arturo Merzario. “That Alfa 33 was a lovely car. Bernie Ecclestone asked me what the engine was like. I told him, ‘Good. Maybe a bit on the heavy side, but powerful and very strong.’ Soon after, he did the Brabham deal with Alfa for F1 engines for 1976.

“At the end of 1975 Emerson went off to do his Copersucar thing, and James Hunt appeared. We had a lot of fun together. We’d known each other since F3, of course, and we had a few flings around London, one or two naughty things going on. He was the golden boy, of course: a good-looking guy, and English. But McLaren was always nice to me, I always got on very well with the mechanics. Dave Ryan wanted to do some Formula Ford on his weekends off, so I sponsored him, £1000 a race.

“In 1975, Emerson and I always had identical equipment. But in ’76 I couldn’t put my finger on why James was always quicker. I knew my cornering speeds were the same – in those days, with the more primitive aerodynamics, you could follow each other closely through the corners. But on the straights he would always pull away. It didn’t demoralise me, it just pissed me off a bit. What none of us knew, until [Cosworth boss] Keith Duckworth told me years later, was that three teams were getting evolution DFVs that year, just for their number one driver. Tyrrell had them for Scheckter, Lotus for Andretti and McLaren for Hunt. Keith told me, ‘Those guys had 40 to 50bhp more than you had.’ I didn’t know, James didn’t know. The mechanics were just told which engine to put in which car.

Whether prototypes or GTs, Mass excelled

“Nobody understood aerodynamics then. At Kyalami I was fed up because my lap times were well adrift of James. The mechanics changed all the springs, checked everything, but the car was doing different things every lap. The mechanics were sure it was me – ‘You obviously didn’t get enough sleep last night, what was her name?’ Then, as they pushed the car in the pitlane, one of them said, ‘Hold on, we’ve found something.’ After a few seconds they said, ‘OK, go.’ At once I went fourth-fastest. As they pushed on the rear wing they noticed that the Gurney flap was only fixed at each end, and not in the middle. It was bowing up and the air was spilling underneath it. They put a piece of tape over it, and that was worth 1.5sec. I finished third, behind Lauda’s Ferrari and James.”

And he surely should have won the 1976 German Grand Prix. It was raining at the start, and everybody opted for wet tyres – except Jochen, who backed his love of the Nürburgring with a gamble on dries. Some parts of the 14-mile lap were glistening wet, some parts were merely damp, but from ninth on the grid, slithering on his slicks, he passed car after car. At the end of the first lap he was in a sensational second place behind Ronnie Peterson, and on lap two, as the track dried and others peeled off into the pits to change tyres, he came through 29 seconds in the lead. Then Niki Lauda had his dreadful accident, and the race was stopped. The grid was reformed in starting order, and Jochen finished third. “The M23 was a good car. The 1977 car, the M26, wasn’t so good, but I still had the M23 for most of the season. I was second in the Swedish GP at Anderstorp, and third in Canada. I did a couple of F2 races for March that year, at Hockenheim and the Nürburgring, I won both of those. And I was now driving for Porsche in sports car races.” It was a fruitful relationship that was to last for more than a decade.

“I felt things breaking, crack, crack, crack… it was my first bad accident”

“I never really liked the Porsche 935, although Jacky Ickx and I won a lot of races with it. The Moby Dick version was better, and I liked the 936 a little bit, but they weren’t exciting. The 956 and the 962, they were absolute magic: very good to drive, comfortable in a long race, tremendous downforce, and just better than anything else. And driving with Jacky was always fun. He is a sensitive character, definitely an introvert, which he hides behind a benevolent exterior. An excellent driver and a lovely guy. We usually raced together, except at Le Mans: I always told Porsche I wanted my contract to cover everything except Le Mans, because I never wanted to race there – even though I usually ended up doing it. I hated the organisers’ arrogance and incompetence over safety. Almost every year, it seemed, we’d lose a driver or a marshal, and guard rails would keel over and launch cars.

“But of course Le Mans was a great challenge, because it was dangerous, and because it was a race of attrition. You couldn’t go flat out, like they can with the diesels today. And it was only two drivers per car, because you could do two hours without the car wearing you out. The later cars with more downforce, like the Sauber C9 and C11, they were harsher, much more demanding because of the cornering forces, and you needed three drivers. I was one of the fitter guys – I never went to the gym, but I ran, cycled, did push-ups and all that. I did the Superstars TV show and, along with Jody, I was best of the racing drivers.”

At the end of 1977 his McLaren F1 contract wasn’t renewed. “Marlboro realised Patrick Tambay was younger and better-looking than me. Then Günther Schmidt, who ran the ATS wheels business, decided to take over the March F1 team. Robin Herd came with the package, and I’d always got on well with him in F2, so it sounded good. But Schmidt had a terrible temper, told everybody how to do their job, told each mechanic how to hold a spanner. Robin walked out after the first two races in South America, saying, ‘I can’t work with this guy.’ I said to him, ‘Please don’t leave, you’re the reason I joined this outfit.’ But he left anyway.” After a trail of retirements Mass was testing the ATS at Silverstone when a radius rod broke on the Hangar Straight, and the car turned sharp left into the sleepers. “I felt things breaking, crack, crack, crack. I smashed my left leg, femur, tibia, knee, and punctured my lung. I was lucky it didn’t catch fire, because the engine was torn off. It was the first bad accident I’d had, and it was the end of me and Schmidt.

After seven Le Mans starts with Porsche, Mass switched to Mercedes for 1988, and won on his second outing in its C9 a year later

Getty Images

“While I was lying in Northampton Hospital Frank Williams came to see me. He said, ‘Next year we’re going to run a full two-car team, and we need a second driver alongside Alan Jones.’ Then Jackie Oliver came in with the Warsteiner guy who sponsored Arrows, and said, ‘Come and drive for me.’ Negotiating from a hospital bed isn’t easy. Warsteiner were promising a lot, and Riccardo Patrese had been going well in the Arrows, so I opted for them in the end, and Frank signed Regazzoni. I will kick myself for the rest of my days… But I liked Arrows, liked the guys, liked Patrese a lot, got on with Jackie. At first Riccardo was young, he didn’t control himself very well, made lots of silly little mistakes. I said to him, ‘We all know you’re quick, why don’t you just try to finish a race? Don’t try to out-brake everybody everywhere, then you’ll earn points.’ From then on he started to finish. I was there for two seasons. The cars were OK. The rocket-shaped A2 – I called it the V2 – was the most misunderstood car. It was too heavy, sure, but the problem was the springing was way out. It generated massive downforce and, when the other big-downforce cars were using 2800lb springs, we only used 380lb. It was way too soft, and we got this terrible porpoising effect; you had to lift off on the straights.”

Jochen had several good drives in his two Arrows years, particularly at Monaco. In 1979 he held a superb third until the brakes overheated. In 1980 he came through to fourth, holding off Gilles Villeneuve’s Ferrari in a stirring battle when a shower of rain turned the track into a skating rink. On the final lap Gilles spun at Mirabeau and then, within sight of the line, Jochen spun at Rascasse. He kept the engine going, got it pointing straight, and finished just ahead of the Ferrari. In the 1980 Spanish GP at Jarama – which because of the FISA/FOCA dispute later lost its world championship status – Jochen was a fine second.

“At the Österreichring that year somebody blew an engine in practice and put down a slick of oil. I skidded off down the hill and into a ploughed field, hit the furrows sideways and flipped, and the rollbar sank into the earth. I was trapped in the car upside down, worried that I’d broken my back. Fortunately I only cracked some vertebrae.” Meanwhile Warsteiner had terminated its Arrows sponsorship, and Mass’ seat was in doubt. “In November I was doing an Atlantic crossing in my boat, and halfway between Gibraltar and the Azores I broke my left leg again. The boat rolled a bit, the boom swung towards my head, I ducked and turned, and my femur snapped. We got back to Casablanca, and I flew to Germany and had a pin put in the leg, which is still there. Then I called Frank Williams and asked him if he had his number two driver for 1981. ‘Dammit,’ he said, ‘I’ve been trying to get hold of you for weeks, but I couldn’t reach you. So I signed Derek Daly yesterday.’

“That left me out of F1 for a year. In 1982 I got involved in the RAM March operation with John Macdonald and Guy Edwards. I brought Rothmans money to the team. I can’t say anything printable about the honesty and probity of those two.” It was an unhappy season, most of all because of what happened in qualifying at Zolder. Jochen set 13th-fastest qualifying time – his best of the season in the uncompetitive March – but blistered his tyres, so he was returning to the pits at reduced speed. Gilles Villeneuve, desperate to out-qualify Ferrari team-mate Didier Pironi after their row two weeks earlier, came over the brow before the fast left/right at the back of the circuit. The Ferrari’s left-front wheel hit the March’s right-rear, and the Ferrari was launched into an enormous accident. “The quick line was on the left, so as Gilles came up in my mirrors I moved to the right. Maybe my mistake was not to give him a signal, to point. I feel deep regret about that. I knew Gilles well, I knew his wife Joann and his kids Jacques and Melanie, we’d spent time together. I did the race the next day, and my engine blew at exactly the spot where Gilles had been flung into the fences. I just sat in my car, thinking about the day before.

Sharing a Mercedes SLS with Sir Stirling Moss in the 2001 Mille Miglia as part of Mercedes work

Motorsport Images/Schlegelmilch

“Three months later we were at Paul Ricard for the French GP. I was in a big slipstreaming queue of cars on the back straight – we were doing over 180mph there. Mauro Baldi pulled out of my slipstream and, as we went into Signes, he got his front wheel between my two wheels. At once I cartwheeled. In the first loop, as it hit the deck, the rollbar snapped off and the thing went on fire, then I flew end over end through all the catch fencing, over the guard rails, over a service road, over a concrete wall into a spectator area. My helmet was ground through and split open. When it all stopped I was right way up, but parcelled up in this roll of fencing, so I couldn’t get out, and I could feel intense heat because the car was really burning behind me. Then suddenly I was engulfed in all this lovely cool foam. I’d ended up near a fire truck. They cut me out of all the fencing, and I had no injuries. My shoulder was a bit sore.

“But I felt somebody was pointing at me saying, ‘Give it up now. The team is s**t, they stole your money, nothing good will ever come of it, give it up and just do sports cars.’ The accident was so eerily similar to the one with Gilles, two cars touching: it was too close. I’d been pretty lucky with my first accident with the ATS, I’d been incredibly lucky with this one. I thought, how much luck do I have?”

He carried on with the Porsches, had a lot of success in America in the IMSA series, and won the Sebring 12 Hours with Bobby Rahal. He ended up doing Le Mans 10 times, had his share of disappointments, but finished second with Vern Schuppan in 1982. But it wasn’t until he moved to the Sauber-Mercedes outfit that he won Le Mans, scoring a great victory in 1989 with Stanley Dickens and Manuel Reuter. In 1991 he led for 16 hours with Jean-Louis Schlesser and Alain Ferté, but the engine failed three hours from the end. In the big silver coupés he also won Spa, the Nürburgring, Donington, Jarama and Mexico (twice), and was very unlucky not to win the drivers’ championship in 1989 – when Le Mans did not count for points. “My role at Sauber included tutoring Michael Schumacher, Heinz-Harald Frentzen and Karl Wendlinger for the Mercedes Young Driver scheme. Frentzen was the easiest, he just jumped in and drove. Wendlinger could be very quick on a single lap. But Michael was easily the most focused, the most analytical.”

“He who knows that enough is enough will always have enough”

Having found time to manage a Lotus-Opel team and then a Mercedes DTM team, Jochen also spent a while as a German-language F1 TV pundit. “It became monotonous after a while, saying the same things every fortnight. But I was doing more and more historic driving for Mercedes with their museum cars. As well as the 300SLR and the big SSK on the Mille Miglia – I think I’ve done that event 18 times – I’ve driven all the great pre-war grand prix racers, W25, W125, W154, even the little 1.5-litre Tripoli car. And the post-war W196, of course. The W25 is lovely to drive – swing axles, narrow tyres, just under 400bhp, you steer it on the throttle. The W125 is much more of a handful, a 5.8-litre twin supercharged straight-eight, 680bhp, spins its wheels in any gear. The W154 came in when they reduced the formula to 3-litres, but that’s a wonderful car, much more modern, V12 engine, good brakes. The little Tripoli car is surprisingly quick, too. And I loved the London-Brighton Run with the 1904 Mercedes. Lining up in Hyde Park at dawn, 500 cars all pre-1905, it’s a staggering sight.”

Other historic duties include racing Anthony Bamford’s glorious Lancia D50 and officiating at Pebble Beach as a judge. And he has succeeded the late Phil Hill as president of the Club Internationale des Anciens Pilotes. Away from racing he’s a partner in a shipyard on Lake Constance, building handcrafted motorboats of mahogany, cedar and ash, and there’s his wind-powered freighter concept, with hydrogen fuel as a back-up when the wind drops. “Very clean, very fast.” He also helps a charity teaching road safety to children, and is making TV documentaries about motor racing history “while some of the old guys are still around”. This is a busy man.

With his Group C Porsche

“Nowadays in F1, with big business involved, there’s a lot of pressure. But the guys today get so much money, they become blasé. You’d think with all that money they’d help each other out if one of them had a problem, but today it’s each for himself. And those managers – some of them get rich looking after nothing. Lao Tzu said, 2400 years ago, ‘He who knows that enough is enough will always have enough’. I like that.

“I have been so lucky in my life. I loved my racing, but I didn’t get all tense about it. Perhaps I should have been more serious about it, juggling this and that, but I’m not made like that. To me life has always been a game. Crossing oceans in an old sailing boat while I was an F1 driver: most would say that was pretty daft. But I don’t regret any of it. You are what you are.”