“One of the reasons there were so many fatal accidents was the way the cars were made. They all had solid axles, so when a car ran over another car’s wheel, instead of something breaking and the wheel coming off, it became a pole-vaulter, and it would start a series of end-over-end rolls. And there were no roll-over bars back then, of course.” Nor proper seat belts, nor flameproof overalls, nor crash helmets worth the name. If ever there was a time when a racing driver was literally absurdly at risk, it was in the sprint cars of the ’50s.

“You have to remember how different the times were,” continued Economaki. “It was only a few years after World War II, and a lot of the drivers had survived that, and figured anything afterwards was a bonus. You didn’t have seat belts in street cars, everyone smoked — the world was not the same place it is now. Racing was dangerous, sure, and nobody gave a thought to it: that was how it was. You got inured to it.

“It was tough, but the racing was phenomenal – what won races in those days was drivers, not cars. The man-machine equation was weighted heavily in favour of the driver, and to me that’s how it should be. They were fabulous days in the sprint cars.”

Now, on this torpid afternoon, I looked over this spooky little track, screwed up my eyes, and tried to picture how it must have been back then. They lent me a buggy to drive round the track, and I stopped often to take photographs. Then they took me for a ride in the pace car, a Ford Mustang, with a driver who knew what he was about. Giving it kickdown out of a turn, he would just reach 70mph before the entry to the next In July ’54, in his Offy-powered car, Sweikert lapped at 101.72mph.

Sweikert lost his life in a fit of temper pursuing another driver

Getty Images

At one point, we parked right at the top of the banking, and it was so steep as to make me uneasy, for I was sure the car was going to topple down. The technique used by the racers, I was told, is to use the banking, rather than the brakes, to scrub off speed.

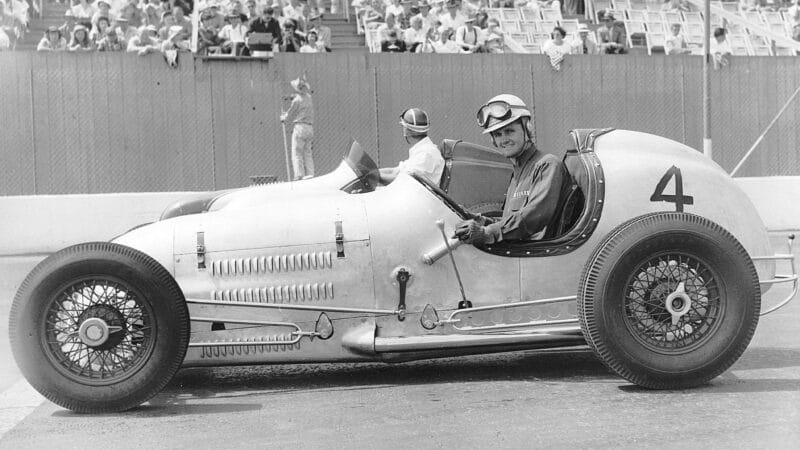

In the mid-’50s, the kings of Salem were Pat O’Connor and Sweikert, major stars on the USAC Championship trail, yet men who continued still to run the sprints.

“If you were successful in them, like those guys,” said Economaki, “you could make good money. The drivers didn’t earn then like they do today — most of them had other jobs, too. O’Connor, for example, was a car salesman in his home town, North Vernon, just down the road from Salem.

“They were good friends, those two, if ferocious competitors on the track. There was no bitter animosity between them, like you found in certain other series. They were very similar — polished, high-type, guys. Most of the guys on the circuit were not like that”

Both, ironically, were to lose their lives in accidents involving one Ed Elisian, emphatically not according to Economaki, a ‘high-type guy’.