Though Ickx led initially, Jochen swept majestically past the Ferrari and thereafter owned the race. But even before the race was over the drivers knew that another tragedy had befallen one of their brothers. Courage had been battling for seventh place with Jochen’s team-mate John Miles when his de Tomaso left the road on the 23rd lap, crashed and caught fire. The Old Etonian perished in the flames.

“I saw the burning car and I saw Piers’ helmet very near to it,” Jochen said. “For some laps I desperately hoped that he had climbed out and thrown away his helmet, but then I realised that Piers, if he had come out, would never have put his helmet down so near to the car.”

Jochen and Piers were so close that his death hit Jochen very hard. They and their wives had had so many adventures. Nina left the circuit with Sally long before Jochen took the flag, and admits that she was angry with him for winning.

“It was odd, but I was angry that Jochen won. It was sort of, ‘How could he win the race in which Piers was killed?’ It was all just so horrific, so disgusting. I was very angry, though not really at Jochen. I was just angry at the whole thing.”

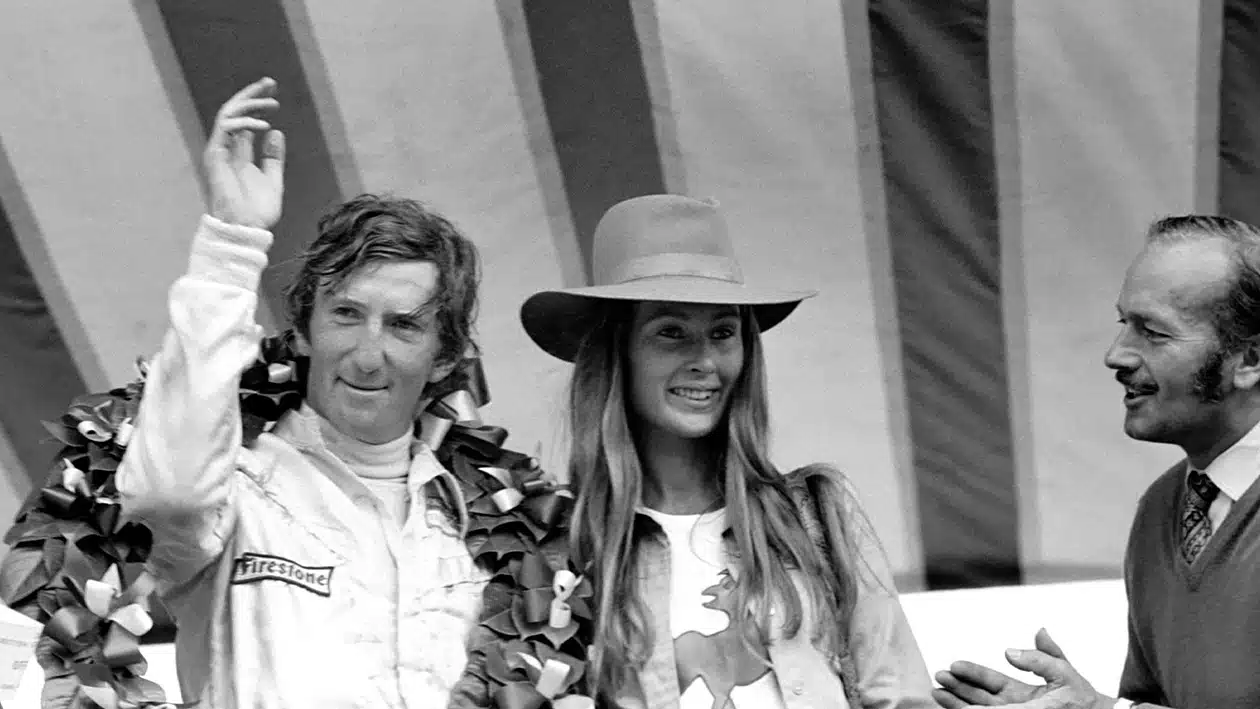

Jochen’s expression on the podium betrayed his own anguish, and the realisation that he had finally got his hands on a car that could take him to the world title rendered the whole weekend bitter-sweet.

Rindt’s grief is plain on the Zandvoort podium

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

On the way to the airport he discussed his future with Bernie Ecclestone. Bernie said if he was minded to stop, he should do it straight away. But Jochen said: “If I want to keep my self-respect, I can’t quit during the season.”

“It was a bad time, obviously,” Ecclestone said. “I brought Sally and Nina back in the plane to London, and Jochen was just terribly upset about the whole thing. He was talking about quitting immediately afterwards, sure, but I didn’t think he would ever have stopped.”

Jochen left Zandvoort traumatised and deeply saddened. It was his third GP success, but it was victory without joy. The tragedy triggered the toughest time in Jochen and Nina’s marriage, as each coped with their own grief while spending endless hours helping Sally in her darkest time.

“The thing was that Piers dying showed it could happen,” Nina said. “When Jimmy died Jochen was shattered. But I sort of pushed it away. I told myself it was a fluke, it couldn’t happen to Jochen. I was brought up with racing because of my father, and I never regarded it as dangerous. When you are young, you just push danger away. Or you couldn’t survive.

“When it was Piers, when I saw Sally and the kids, I realised that it was really serious.”

“Beltoise had been through hardships, but what on earth possessed him to say such a thing to me?”

Meanwhile, a thought kept tormenting Jochen. At Christmas they had spent time with the Courages skiing in Zurs, together with a friend called Ernst Moosbrucker. “He was such a nice young man, and he died very quickly of cancer,” Nina said.

Now Jochen would wonder, over and again, “Is it better to die the way Ernst did, or to die instantly, like Piers?”

“It was awful,” Nina said. “Jochen would ask that question, and he thought perhaps it was better to go like Piers. We lost all three of them that year…”

Piers’ death was the most traumatic thing Jochen had ever faced in his young life. “He was hit hard by Jimmy’s death,” Nina said. “We’d spent a lot of time with him in Paris, a lot of time. Jochen was completely shattered then because that was the first time for him… But, yes, Piers was more traumatic, emotionally worse, because they were such close friends.”

And it set Jochen worrying that he might be the next green bottle to fall from the wall.