Age of innocence — the thrill of 1960s racing by Gordon Murray

Exhaust smoke, noise, towering characters, innovation, pushing the boundary of possibility – all things Gordon Murray loved about motor racing in the 1960s. As he sets out here, today’s F1 could learn from this decade

Getty Images

I fell in love with motor racing when I was just five years old and, growing up in South Africa, not a month went by when my father and I didn’t go to a race. There was a lot of racing there in the 1960s, teams and drivers coming from Europe, and our own Sunshine Series. Before I had a car I used to hitchhike to Kyalami for the Grand Prix.

Ferraris at Monza, 1964.

Silverstone, 1960 –Graham Hill (No4) is inch-perfect with his BRM in the International Trophy

The Nine Hours was the big event. I saw all the great sports cars, Ferrari 250 GTO, 250 LM, Porsche 904 and 906, Ford GT40, it was exciting to see all those cars. At the Grand Prix you could walk round the back of the pits and there was Jimmy Clark just sitting there. It was surreal, and I just wanted to get to Europe.

“You could walk round the back of the pits and there was Jimmy Clark. It was surreal”

Back then racing was an adventure. There was an irreverence about it that appealed to me enormously, and there was a freedom from the engineering point of view – the cars were all different. The 1.5-litre formula brought out the best in designers because, with only that much horsepower to play with, things like aerodynamics, suspension and driver seating position really became important. The innovators rose to the top. That appealed to me because innovation is a rebellion if you like. There’s only ever been two types of designers, the evolutionary ones who see what everyone else has done and very carefully move that forward, and then there’s the rebels like Colin Chapman who kept breaking the rule book. I definitely grew up in the latter mould.

Another crowd-pulling name – Jack Brabham, 1960 Argentine GP.

Jim Hall of Chaparral was at the forefront of change

Getty Images

The Coopers were part of my inspiration, starting the rear-engine era, but their engineering design was evolutionary, safe and solid; they kept leaf springs for a long time, they stuck to multi-tubular frames rather than space frames, and yet they had some completely revolutionary ideas like the rear engine. The Cooper 500 had magnesium wheels with the brake drum cast into the wheel. That stuck in my mind for a long time. When I designed the Rocket it was pure nostalgia, inspired by my favourite late ’50s and ’60s racing cars like Coopers, Vanwalls, the Lotus 16, so I was very influenced by that period.

I admired Colin Chapman even if his drawings looked like they’d been done by a 10-year-old. He wasn’t a design engineer per se, he was more like an engineering-led version of Enzo Ferrari who pulled in and steered some fantastic engineers on both the chassis and engine side. Chapman was an ideas guy, not a detail designer. He surrounded himself with good people –nearly all the early Lotuses were done by Mike Costin.

Temperatures soar at Monza in the pits before the 1963 Italian GP; Motor Sport’s Denis Jenkinson, right, has a prime position among the Lotus crew

I admired the way Chapman took such big steps forward but, interestingly, he took a long time to adopt the rear engine, persevering with the Lotus 16. Apart from that he led the way and didn’t follow other people. My favourite racing car of all time is still the Lotus 25. It really is a fantastic piece of design even if it did have rocker front suspension, but then everyone used that in those days. Then there’s his road cars. When I first saw the Elan in a magazine I thought, “Wow, backbone chassis, lovely little twin-cam engine, 700kg, very pretty car.” So yes, Chapman has been a massive influence for me.

Gordon Murray was quick to buy a Lotus Elan

You have to remember that in the 1960s people were doing very basic stress calculations, if at all, so it was a lot of gut feel and experience, rather than scientific calculation. Saving weight in a racing car comes with the territory. The closer you got to the bone the more fragile the car. I did push the boundaries on my cars, and again that was probably a Chapman influence.

When it comes to aerodynamics I was always interested in that area and experimented from day one at Brabham. Jim Hall at Chaparral, Chapman and Mike Costin were also leaders in the field, with sliding skirts to create a vacuum, and Hall had the fan principle on the Chaparral but that was run by an extra engine which was the easy way of doing it.

Poetry in motion: Jim Clark in a Lotus 25, on his way to winning the 1962 British GP – the last time the race was hosted at Aintree

Getty Images

An innovation that was never going to work was four-wheel drive because of the complications, the added weight and the balance of the car. You were never going to get a balance between high-speed and low-speed corners on different circuits without modern electronics intervening to change the torque split. It was immediately obvious to me that a four-wheel-drive Formula 1 car wasn’t the way to go. It was a dead end, like the Lotus 72 which had inboard front brakes and two extra driveshafts. That was never going further.

“My favourite racing car of all time is still the Lotus 25. It’s a fantastic piece of design”

The ’60s and ’70s were a fantastic time in Formula 1. There was freedom of expression, a very interesting and diverse period right from the 1.5-litre formula through to the late ’80s. As an engineer you could have an idea overnight, draw it, get the bits on the car, and take it to the next race with a new solution to a problem.

There was stability with the Cosworth engine, although at Brabham we kept changing engines, getting the Alfa flat 12 and the V12, and then the BMW which caused me to keep innovating the design of the cars. The beauty of the Cosworth was that it was so easy to bolt a DFV to the back of the monocoque and go racing. When you have engine stability you can then focus on transmissions and improving the overall aerodynamics, which is interesting and rewarding for an engineer.

Kids today won’t believe you, but there were different-looking cars in F1 in the 1960s – as this Jack Brabham/Chris Amon tussle at Kyalami in 1969 shows

Motor racing has lost something more recently with all the new technologies. There are two big issues: the rules are very narrow which means the cars are super-huge and long, and essentially they all look the same; then there’s the ship-to-shore communications which means the driver gets told how to run his race, how to manage tyres and temperatures. That ruins it for me, it really does. It’s supposed to be a drivers’ championship so I’d like to see them being more holistic, more mechanically sympathetic, reading the way the tyres and the brakes are working like they did in the 1960s and ’70s.

Coopers and Ferraris – both an inspiration – thunder around Reims, 1960.

Getty Images

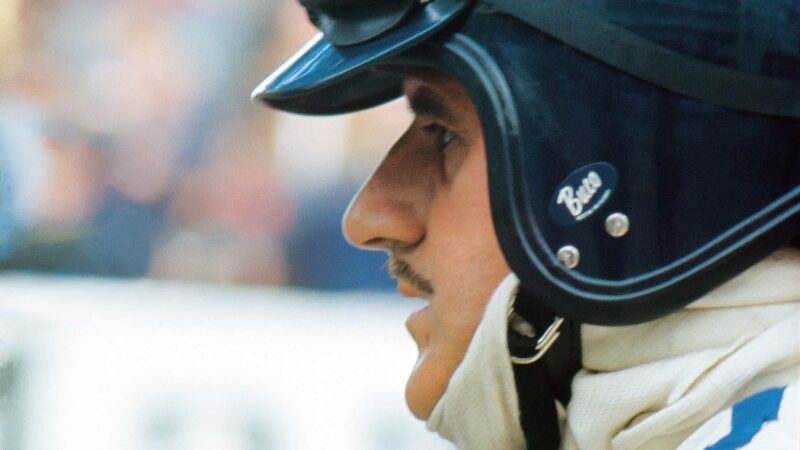

Hill earned his pair of F1 titles in the ’60s

Getty Images

Engineers just can’t make the big steps forward any more, like introducing carbon brakes, or carbon fibre as a structural element. Strategic pitstops, these were worth seconds a lap and you can’t do that kind of thing any more. At least they now have 18in wheels and they’ve made the front and rear wings less important, allowing designers to move more downforce to the centre of gravity, which means a car can follow another out of a corner and overtake more easily.

“I remember selling everything to make enough money to come to the UK, giving me £1130”

Going back, to what inspired me as a young man in South Africa, I remember selling everything to make enough money to come to the UK. I sold my road car, my racing car, everything, giving me £1130. Even though I had no job and nowhere to live, when I arrived I spent £840 of that on a Lotus Elan in the first month. So that’s how inspired I was by anything Lotus did, right from when I was a teenager in the 1960s.

Jenks in conversation with a DFV, Zandvoort, 1967.

Getty Images

End of the decade, Monza, 1969, in chase of Jackie Stewart

I devoured anything Ferrari was doing with engines. They had some of the greatest engine designers that ever lived – Vittorio Jano, Gioacchino Colombo, they were geniuses. Then there were the guys at Fiat and Abarth like Dante Giacosa who designed the Fiat Cinquecento, another man I admired back then.

A Lotus Elan and a Cinquecento in the garage? That sounds pretty good.