During 1969 Chapman pursued the 4wd theme in Europe with the unloved DFV-engined 63. The following year he unveiled the 72, which echoed the 56’s dramatic wedge shape.

But the turbine idea didn’t go away, and late in 1970, Chapman finally had his F1 spec car ready to run. Fitted with large front and rear wings, it was dubbed the 56B. The car was based on an Indy chassis; some reports say it was actually built from the remains of 56/2, the car Spence crashed.

Young and eager, Fittipaldi was delighted to be asked to handle the new machine. Then he drove it…

“My first reaction was to be very excited,” he recalls. “The first time I tried it was at the proving ground at Hethel. John Miles was testing the car, and it was freezing. It was the first time I saw the car as an F1 package. When the car went by it was amazing to hear the tyres more than the engine.

“At the end of the runway there was a hairpin, and John lost the brakes. He went straight over the fence into the fields. When I saw that, my leg started shaking because I was next in the car. He was about half a mile away from the track, and was extremely lucky. John came back completely white, he said, ‘Emerson, your turn now. Good luck.’ They repaired it, and I drove it carefully, taking care of the brakes.”

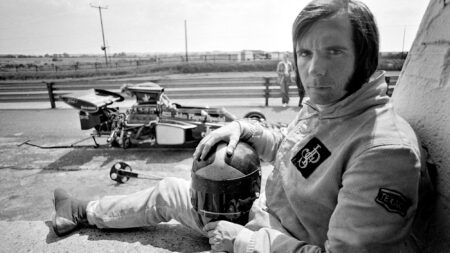

Fittipaldi heads into history in the Lotus 56B, the first turbine-powered grand prix car, at the Race of Champions, Brands Hatch 1971

Grand Prix Photo

Miles and Fittipaldi discovered what Hill had found out two years earlier; to keep the thing going you had to stay on the throttle.

“There was this delay. You had to keep turbine speed up, and to do that you had to use the power against the brakes, just to keep the turbine going. That’s what happened to John – the brakes overheated.

“When you got the car ready to run, and it was just idling, the engine was going at 90mph if you didn’t hold it on the brakes! It was scary. The exhaust pipe was maybe 10 inches behind your head, and sometimes it was blowing big flames.”