Simple as that. Portago might have been talking about golf or fishing, a hobby. As it was, he bought a Ferrari, and looked for a race. Harry Schell suggested that he partner him at the Buenos Aires 1000Kms. There are those who get started at Snetterton on a Sunday, and those who begin with a world championship sportscar race in South America.

“The problem was, Harry was frightened I’d break the car in practice, so he wouldn’t let me drive. He did the first part of the race, then came in, and said, ‘Okay, now you drive.’ I’d never driven a car with a manual gearbox before.”

Maybe my favourite line from the whole interview comes now: “At Buenos Aires, we had a bit of trouble with the clutch so, before Sebring, Harry thought we should take it to pieces. When we put it together,” Portago says, “there were 53 nuts and bolts left over — and you know what? The clutch didn’t break at Sebring. The back axle did.”

Back in Europe, Portago bought a Maserati to replace the Ferrari, learned how to change gear properly, even to heel-and-toe. And he obviously progressed quickly and well. By the end of 1954 he’d won several times: “I thought I’d arrived — thought Ferrari should give me a contract.” Enzo declined to do that, but sold Portago a Formula 1 Ferrari.

Most of the 1955 season was lost when he crashed in practice for the International Trophy at Silverstone, badly breaking a leg. Towards the end of that year, he reappeared at the Oulton Park Gold Cup; his autograph adorns my race programme.

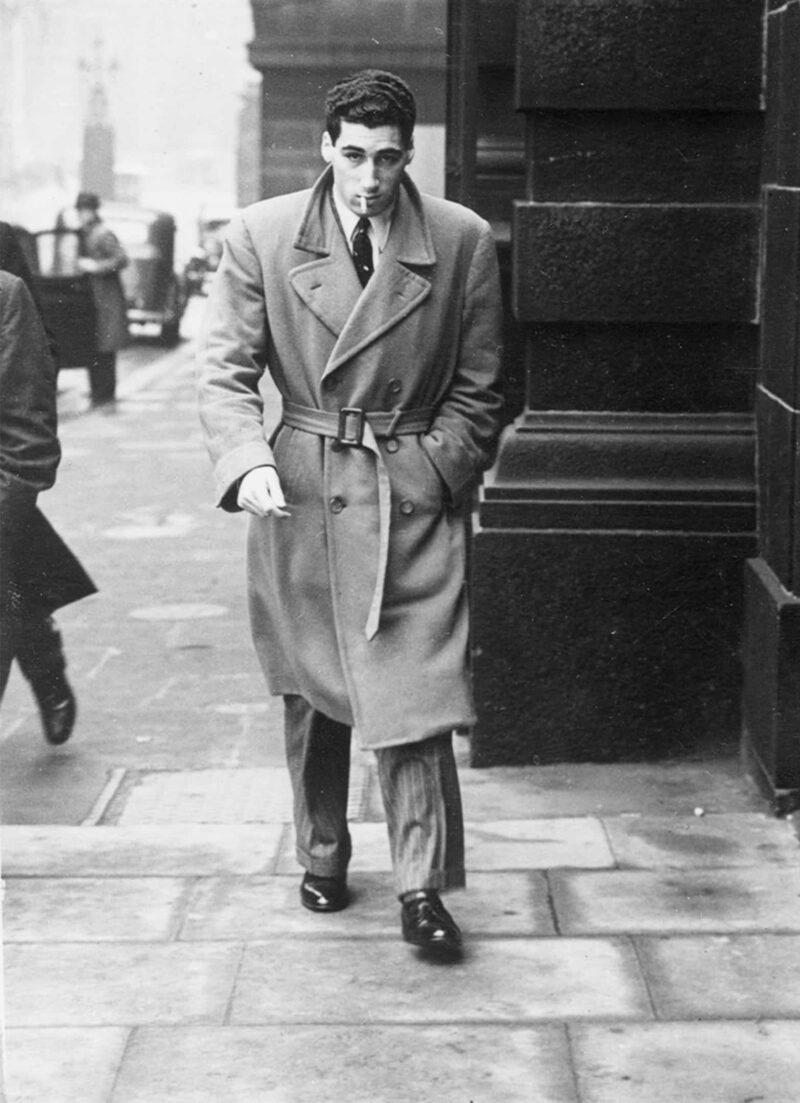

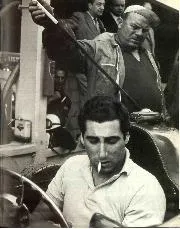

A heavy crash at Silverstone did little to dampen Portago’s racing spirit

Getty Images

In late-season sportscar races, Portago did well, and this time a Ferrari deal was forthcoming. For 1956, he signed up as fifth driver, to Fangio, Collins, Castellotti and Musso.

“With Portago,” Enzo Ferrari said, “there was no such thing as backing away from difficulty. After his accident at Silverstone, his ambition only got stronger.

“He was a kind of magnificent hippy, with long hair, old leather jacket. No doubt he made an impression on women, because he was a tall and handsome man. But what sticks in my mind is that gentlemanly image which always managed to emerge from the crude appearance he cultivated. A good racer.”

“When I pass someone like Stirling, I think, ‘This is rather peculiar— what’s wrong with his car?’”

One who came to know him well was Phil Hill: “When I first met him, in early 1954, he knew absolutely nothing about race cars. Nothing! Never even driven anything with a manual shift. But he was a natural athlete, and he learned.

“He was also ahead of his time, in that he was the first guy I ever met who deliberately dressed down, let’s say. He wore this scruffy leather jacket, shaved about every four days, looked like he had nothing. Then he gave me his card one day, with his address on Avenue Foch in Paris — and that’s when I realised you could be fooled by appearances.”

“Are you interested in cars?” the interviewer asks Portago at one point.

“No, not at all,” comes the reply. “For me, a car is either a means of getting from A to B, or it’s something to race. I would say that half the drivers have some mechanical knowledge, and the other half— of which I am one — have none at all. If I want to terrify the mechanics, I walk towards my car with a screwdriver!” I can’t really imagine ‘Fon’ studying telemetry far into the night.

“I have a complex about Fangio and Moss,” he says. “I may be able to pass them, but I couldn’t stay ahead of them without going off the road. It’s perfectly feasible to follow them, but if I have to lead them — set the example, if you like — then it’s easy for me to miss my braking points, and so on. In fact, when I pass someone like Stirling, I think, ‘This is rather peculiar— what’s wrong with his car?’”

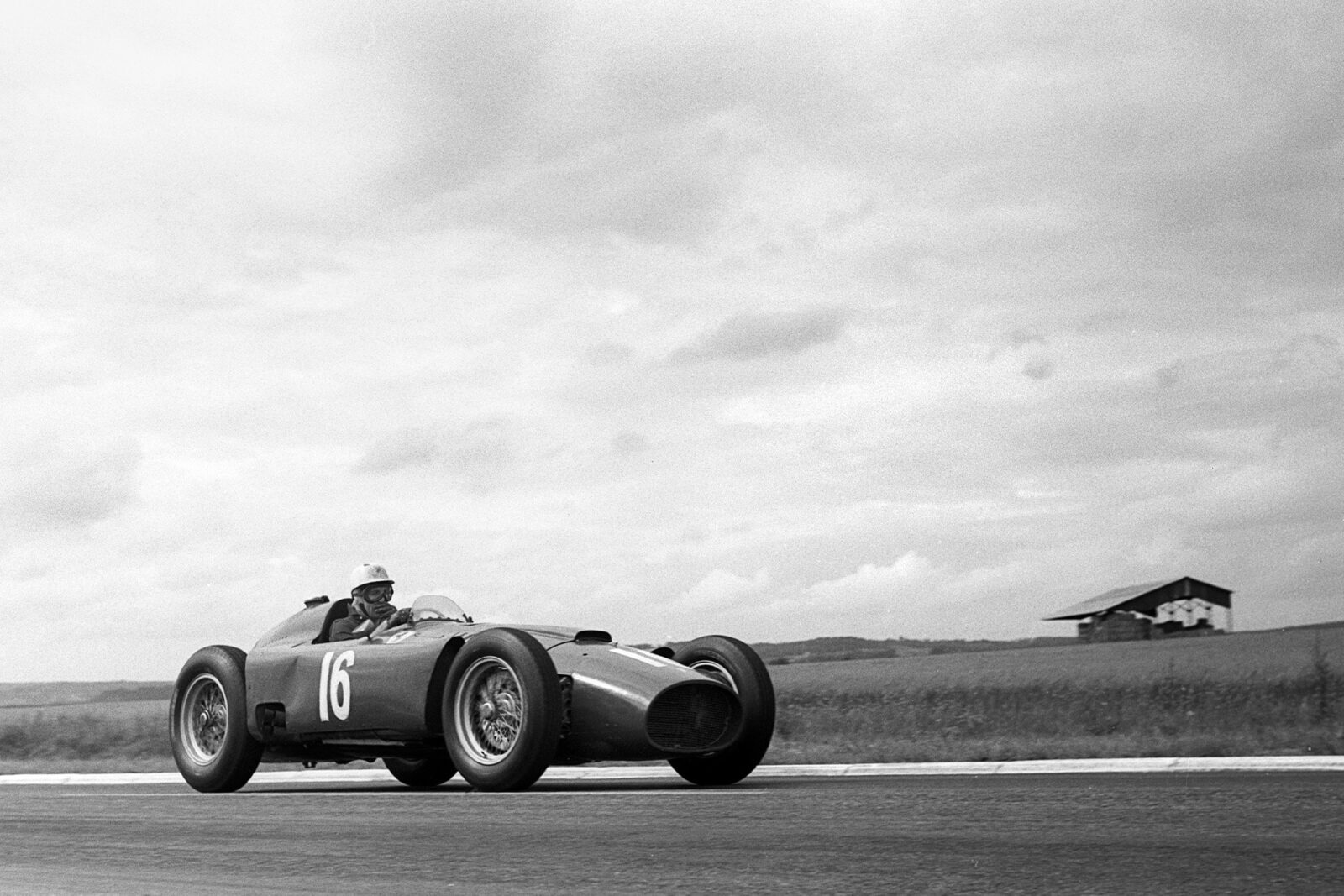

Despite his inexperience Portago’s ability was supreme

Getty Images

Portago’s natural ability must have been considerable, however. These comments were from a man with only a couple of years’ experience, and clearly he saw nothing remarkable in being able to run at competitive speeds. Amazing, too, is the way racing drivers looked at safety in those days. What did he wear? “A short-sleeved sports shirt, light trousers, and those soft shoes bicycle racers use.”

Why not overalls?

“I don’t believe in them — if you get gas on your clothes, and it catches fire, you have a much harder time getting out of overalls than out of a shirt and trousers. So I dress very casually.”

If racing were more of a game for gentlemen in those days, the cutting edge was nevertheless there.