The notoriety of the Pebble Beach event itself, together with his manner of winning it, called this young Californian’s talent to the attention of the racing world. Soon he was driving other people’s cars along with his own new C-type Jaguar, refining his style every time out. Winning major club races again and again across the US bolstered his reputation until, in 1958, he was called to the Scuderia Ferrari. That first year he co-drove a 250 TR sports racer to victories at Buenos Aires, Sebring and Le Mans. By the end of the year he was a Ferrari F1 driver.

Not under happy circumstances, though. As was all too common in those days, the position opened when fellow team member Peter Collins was killed at the Nürburgring. Intently introspective, keenly cerebral, tautly strung, Hill struggled to shrug off the dangers in what he was doing.

“Within a 15-month period,” noted Phil’s close friend John Lamm in an interview for Road Track magazine, “Phil’s Ferrari team-mates Luigi Musso, ‘Fon’ de Portago, Peter Collins, Mike Hawthorn and Jean Behra were gone.

“’It sounds cold, thinking about it now,’ Phil explained. ‘They were all good friends, and I was living on Peter Collins’ yacht in Monte Carlo at the time of his death. But we were right in the middle of a very dangerous period in automobile racing, when people were buying it left and right and had been for quite a while. We were very defensive about anybody trying to get into the life or death aspects of racing. We tried to avoid it and not talk about it.

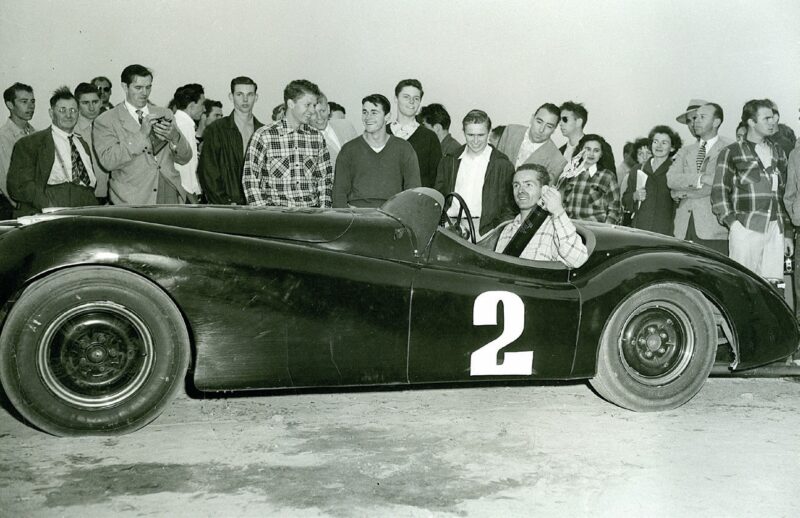

Happier times in 1952 at the wheel of a Ferrari 212 Export. He gained a reputation as the man to beat on America’s West Coast.

“‘In retrospect, I’m pretty certain we knew it was a losing discussion at the time. We would have had a tough time rationalising why it was OK to continue. In that atmosphere, a lot of things that don’t make sense now were logical then.’”

The mental turmoil gave him a nervous, apprehensive edge. At one point he suffered an ulcer. Writer Gerald Donaldson, quoted him as saying, “Racing brings out the worst in me… makes me selfish, irritable, defensive. If I could get out of this sport with any ego left I would.”

Yet he did not get out, not then. Danger be damned, he was resolved to prove himself. As the US journalist David Malsher-Lopez put it last year, “Not a man of bullish self-confidence, then, but steely determination.”

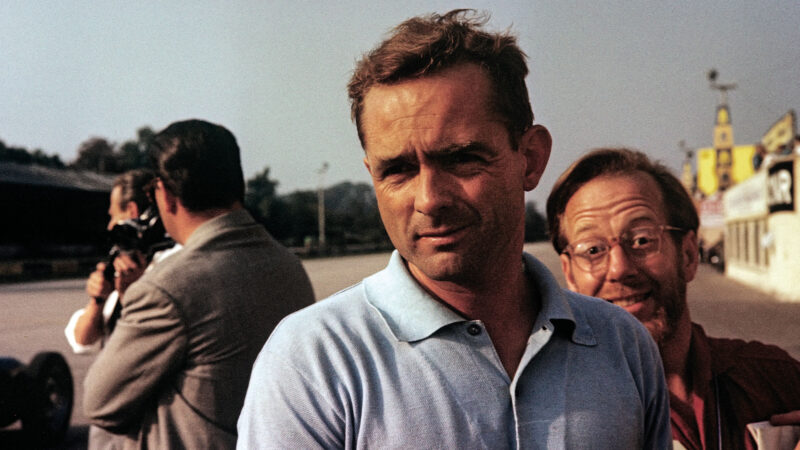

Driving a ‘Sharknose’ at Zandvoort in his title-winning season

Add to that an iron-clad capacity to focus on the job. Stepping into a racing car seemed to flip a switch. If Hill had been at his ‘worst’ before the race, once it began his best came out. He handled the machine with sensitivity and grace, running fast without whipping his mount, thinking strategically, keeping his mind on the finish line and reaching it often in an era when many didn’t.

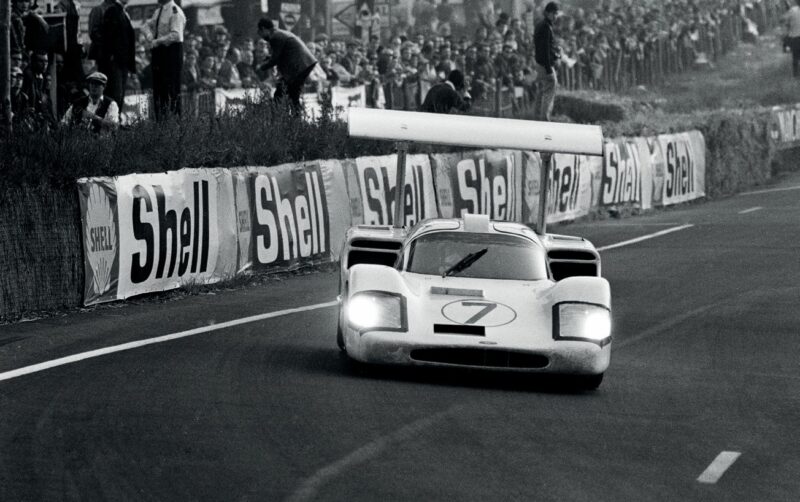

It is a tragic fact that Hill’s day of triumph is shrouded in horror. No one can forget that his Ferrari team-mate, Wolfgang von Trips, died in a savage accident that also took the lives of many spectators. Until that instant at Monza the German driver had the better chance of taking the title. Post-race photographs show smiles on winner Hill’s face, but the man himself said there was no joy behind them.

By haunting coincidence Mario Andretti, the second American driver to become champion, did so at the same cost, when his Lotus partner Ronnie Peterson perished. At the same circuit.

Thus both Hill and Andretti had to fight the same internal war of opposing feelings.

The new F1 world champion keeping up appearances at Monza on September 10 1961, knowing that his team-mate had died

Phil Hill was a Ferrari works F1 driver from the last part of 1958 through to 1962. During the three full seasons he rode the Prancing Horse, ’59 to ’61, he won a total of three grands prix. Not a sensational percentage, but one worthy of respect.

Especially so for someone whose youth was not bathed in the culture and mystique of European F1. Hill himself assimilated before many of his compatriots, but to most Americans of his era Formula 1 was a ‘foreign’ form of the sport and they had to be sold on it. Having one of their own become world champion was a powerful selling point — not least for his Italian employer, for whom America was becoming his marque’s most important market.

“He is perhaps the most underappreciated world champion in F1 history”