Quite obviously the best driver in the team, Surtees was never one to bend the knee, but his worst sin, in the eyes of Dragoni, was failing to be Italian. Bandini was the team manager’s blue-eyed boy, and although Lorenzo always got along well with John, there was nothing anyone could do to prevent Dragoni’s infamous ‘briefing’ against Surtees, particularly in the end-of-the-day telephone calls to Maranello, where Enzo Ferrari awaited.

Dragoni, a political animal before the phrase had even been thought of, did everything possible to destabilise the position of Surtees in the team, minimising his achievements, playing up his mistakes, ascribing unfounded statements to him. After one punch-up too many, at Le Mans, Surtees went to see Ferrari, and the Old Man unfathomably decided on instant divorce.

No one was more upset at the news than Bandini, now propelled into the role of team leader, a position he did not entirely savour. For Reims he was to be joined by Mike Parkes, Maranello’s other Englishman, but emphatically not a bosom buddy of Surtees.

Surtees, for his part, was immediately contacted by erstwhile team-mate Roy Salvadori, now team manager at Cooper. A deal was swiftly struck, and although a Cooper – with an ageing Maserati V12 engine – was hardly the quickest car in town, Jochen Rindt had finished second to Surtees at Spa, so obviously there was some potential there.

Bandini breaks down

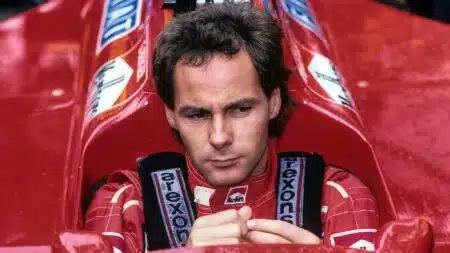

National Motor Museum/Getty Images

Reims seemed to bear that out, for in qualifying John succeeded in splitting the Ferraris, six-tenths slower than Bandini, seven-tenths faster than Parkes – who did remarkably well to make the front row on his F1 debut. Lining up behind them were Brabham and then three more Cooper-Maseratis, the factory cars of Rindt and Chris Amon, and Rob Walker’s car for Jo Siffert. A total of 17 cars would go to the grid.

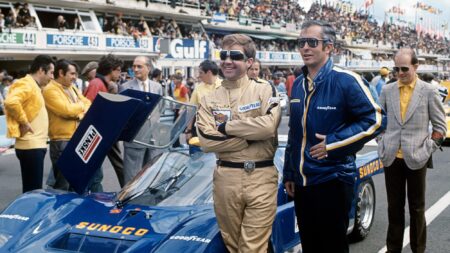

Forty years ago, of course, it was still possible to buy paddock passes, and it was a delight to find some still available. In we went that late Saturday afternoon, collecting autographs here and there, watching Surtees in earnest deliberation with Salvadori, listening to Colin Chapman attempting to converse with Pedro Rodriguez…

Pedro had been drafted into Team Lotus in place of Jim Clark. During Thursday practice Jimmy had been hit in the face by a bird, suffering a badly swollen eye, and was advised not to race.