30 earth-shattering moments that changed motor sport

Our roll-call of motor sport’s pivotal, game-changing moments

As you might imagine, compiling a top-30 list of motor racing’s pivotal happenings was a headache of formidable proportions. Through a whittling-down process that involved much scribbling in notepads, email wrangling and event face-offs, we eventually settled on a score-and-ten of earth-shattering moments from across the many disciplines of motor sport – and Netflix’s Drive to Survive hasn’t made the cut-off (but gets a mention). From the initial running of the Indianapolis 500 in 1911 up to Formula 1’s rebirth under the aegis of Liberty, our list takes in engineering innovation, business deals, bumper-to-bumper battles and many other stand-out instances that proved to be game-changers on the track.

1962

Cooper and Jack Brabham trigger the Indy 500 rear-engined revolution

Together, they’d turned Formula 1 back to front. Then, Cooper and Jack Brabham kicked the doors in for another rear-engined revolution, at the revered home of the big-beast roadsters. Brabham took a rookie test in October 1960 in a lowline T53 and lapped only a couple of mph off the 1959 pole time. It only confirmed the establishment’s fears and spooked officials who thought green cars at The Brickyard were bad luck. They were – for the roadsters.

The following May, Brabham criss-crossed the Atlantic to qualify at Indy and race at Monaco and Zandvoort, then returned to start the 500, above. Coventry Climax had stretched an FPF to 2.7 litres, Dunlop had provided special asymmetric tyres and Kleenex millionaire Jim Kimberly had made John Cooper an offer that made him beam. The double world champion started from the fifth row. Lacking grunt on the straights, but speedy in the turns, Brabham fitted in. Ninth was a sign of what was to come. Colin Chapman took note.

IndyCar’s rear-engined revolution

2012

Lauda talks Hamilton into a Mercedes

Ross Brawn opened the door, but Niki Lauda pushed Lewis Hamilton through it. Then ‘only’ a one-time world champion, Britain’s hero was minded to stick on McLaren rather than twist on Mercedes. Hamilton was wary of Lauda, who had been critical as a pundit. But he took the call because, well, it’s Lauda, who then knocked on his hotel door it the Singapore GP.

The seeds of friendship were sown, and the three-time champion triggered the most bountiful driver-team partnership F1 had seen. After Niki’s death in 2019, Hamilton told Mark Hughes: “Without his support I probably wouldn’t have made the switch.”

1977

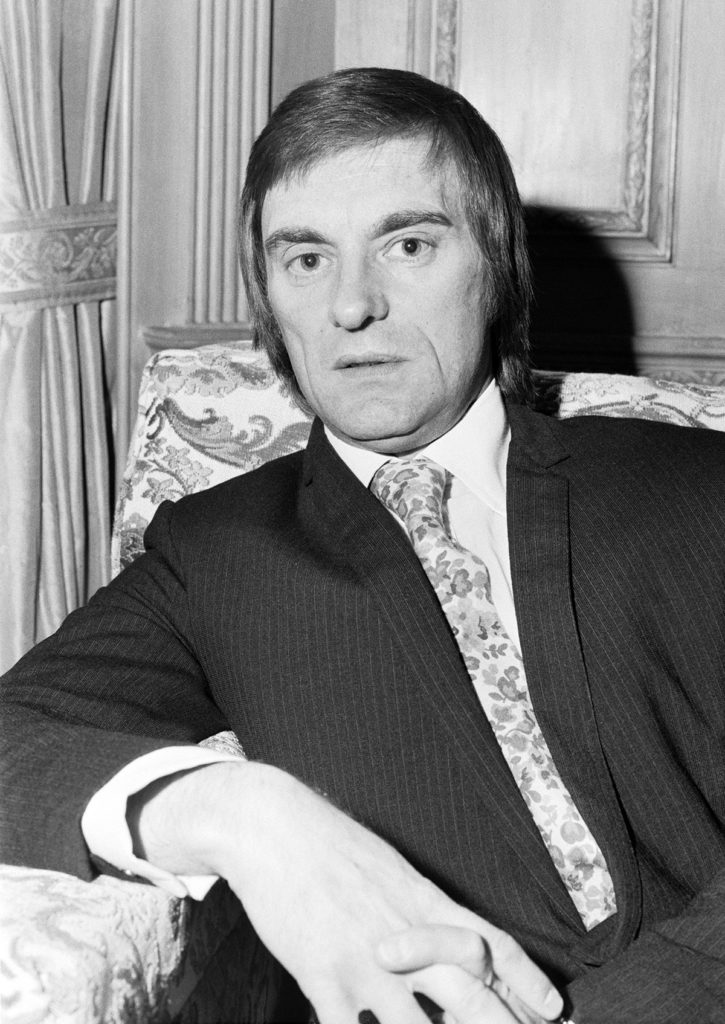

Patrick Head says “yes” and creates an F1 powerhouse

Frank Williams Racing Cars had enjoyed a successful first season in 1969, Piers Courage taking a brace of second places in the team’s Brabham BT26A, but the following campaigns would be difficult. The team carried on after Williams’s friend Courage was killed during the 1970 Dutch GP, but it was rarely competitive and ran a rotating cast of drivers. Financial worries became a constant, too, and before the 1976 season Williams sold a 60% stake in his business to Canadian industrialist Walter Wolf.

Williams left and set up again as Williams Grand Prix Engineering – and promising engineer Patrick Head, above, went with him. Head’s FW06 was neat and reasonably competitive but the following FW07 embraced Colin Chapman’s ground-effect principles and took them to a higher plane. Williams became a GP winner in 1979 and world champion, with Alan Jones, in 1980. Frank was on his way to becoming one of the most successful entrants in F1 history – and Patrick Head was a crucial pivot.

1955

Mercedes pulls the plug on motor sport and creates racing history’s biggest ‘what could have been’

“The complete withdrawal by Daimler-Benz is an unhappy thing for many of us, especially those interested in technical development,” wrote Denis Jenkinson in December 1955. “But, on the other hand, they had monopolised racing to such an extent that their withdrawal will at least allow someone else to win.” It was in Stuttgart at the end-of-season celebrations for Mercedes’ near-whitewash of international motor sport that Dr Fritz Nallinger confirmed the company’s complete withdrawal, beyond the Formula 1 pull-out which had already been made public back in the summer.

Nine grand prix wins from 12 starts over two seasons, victories for the 300 SLR on the Mille Miglia, Tourist Trophy, Targa Florio, Eifelrennen and Swedish GP, plus Tulip Rally and Liège-Rome-Liége triumphs for the 300 SL… Jenks had a point. Whether we believed the official reason – mission accomplished, it is time to focus on ‘passenger-car development’ – or how much the ongoing fallout from the terrible Le Mans disaster had coloured the board’s view of motor sport, it didn’t really matter. The effect was the same: having raised the bar, just as it did in the 1930s, the Mercedes exit left a vacuum. Vanwall filled a large part of it in 1957-58 – but imagine if this rising British force, plus Ferrari and Maserati, had faced the full force of a still-active Mercedes. For whom would avowed patriot Stirling Moss have chosen to drive? And had he remained in silver, how many world championships would he have won?

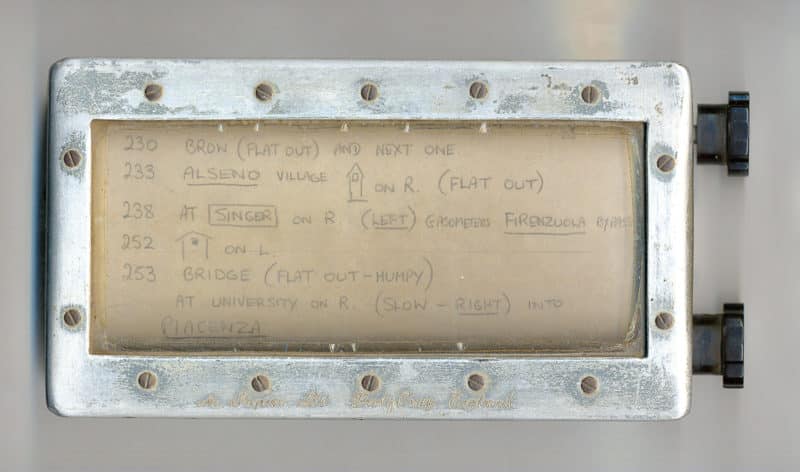

Motor Sport magazine made its mark on racing history when writer Jenks, (below, comedy specs), gave the world pacenotes at the 1955 Mille Miglia – although the idea wasn’t his

1955

Pacenotes

“Hundred square left, 200 K right four, 100 flat over crest into right two, tightens, don’t cut…” Pacenotes are so firmly embedded in rallying’s glossary that it’s hard to imagine a time when they didn’t exist, but…

In 1955, Motor Sport played a role in their creation. For that year’s Mille Miglia, Mercedes offered American driver John Fitch the chance to drive a factory-prepared 300 SL – and he invited our correspondent Denis Jenkinson to accompany him, as he had navigational experience on the event.

As Fitch told us in 2010, “Jenks came to see me and we discussed doing a full recce. Rather than using a big pad of paper or a fat notebook, I suggested we wrote everything onto a roll of paper that could be mounted in a box and wound on progressively. Then Stirling asked Jenks to go with him and I agreed, so Jenks took the roller idea.”

Driving solo with Jenks tucked in alongside, Moss completed the 1000 miles in 10hrs 7min 48sec, an average speed of 97.96mph; without notes, Fitch finished fifth.

1968

Full-face helmets – racing never looked the same since

Time was that racing drivers competed wearing little more than a flimsy linen cap and goggles to the north of their shoulders – though Tazio Nuvolari, clearly big on safety, preferred leather. Not until 1952, the third season of the F1 World Championship, did the authorities make it compulsory to wear a helmet with a hard shell, albeit light years removed from the lightweight composite cocktails we know today.

US firm Bell – which evolved from hot rod enthusiast Roy Richter’s speed parts business in California – was first to introduce a mass-produced racing helmet, the 500, in 1954. It would be another 12 years before the world’s first full-face helmet, the Bell Star, emerged from the same source – and it was Dan Gurney, left, who pioneered its use in competition.

Being tall, Gurney was prone to being peppered by trackside detritus. Earlier in his career he had experimented with leather masks in a bid to protect his face – and in 1968 he turned up at the Indy 500 wearing a Bell Star. He introduced it to F1 a few weeks later, during the rain-lashed German GP, and within a couple of years full-face helmets had been adopted by most top professionals.

Mario Andretti was the last driver to win the Indy 500 with an open-face helmet, in 1969; in 1974, Surtees privateer Leo Kinnunen became the last F1 driver to compete wearing one.

1971

F1 adopts slick tyres and they have been with us ever since

Formula 1 was a slow adopter when it came to slick rubber. American firm M&H was first to put untreaded tyres into production during the 1950s, for the benefit of drag racers, and Michelin brought them to Le Mans in 1967. Firestone had made a tyre with very little tread for Indianapolis in the 1950s – and a decade later Dunlop was producing ‘almost slicks’ for grand prix racing.

The first true slick did not appear in F1 until 1971, however. In his report of that season’s Spanish GP, Denis Jenkinson wrote: “All the Firestone users had a new type of tyre available, which was a pure drag-racing ‘slick’ of solid rubber with no tread whatsoever.”

Jacky Ickx, above, finished second; Goodyear was swift to follow Firestone’s lead and Jackie Stewart recorded the first F1 victory for a pure slick in that summer’s French GP. In dry conditions, slicks have been an F1 fixture almost ever since – the exception being 1999-2008, when the FIA mandated grooved tyres in a bid to curb cornering speeds.

1987

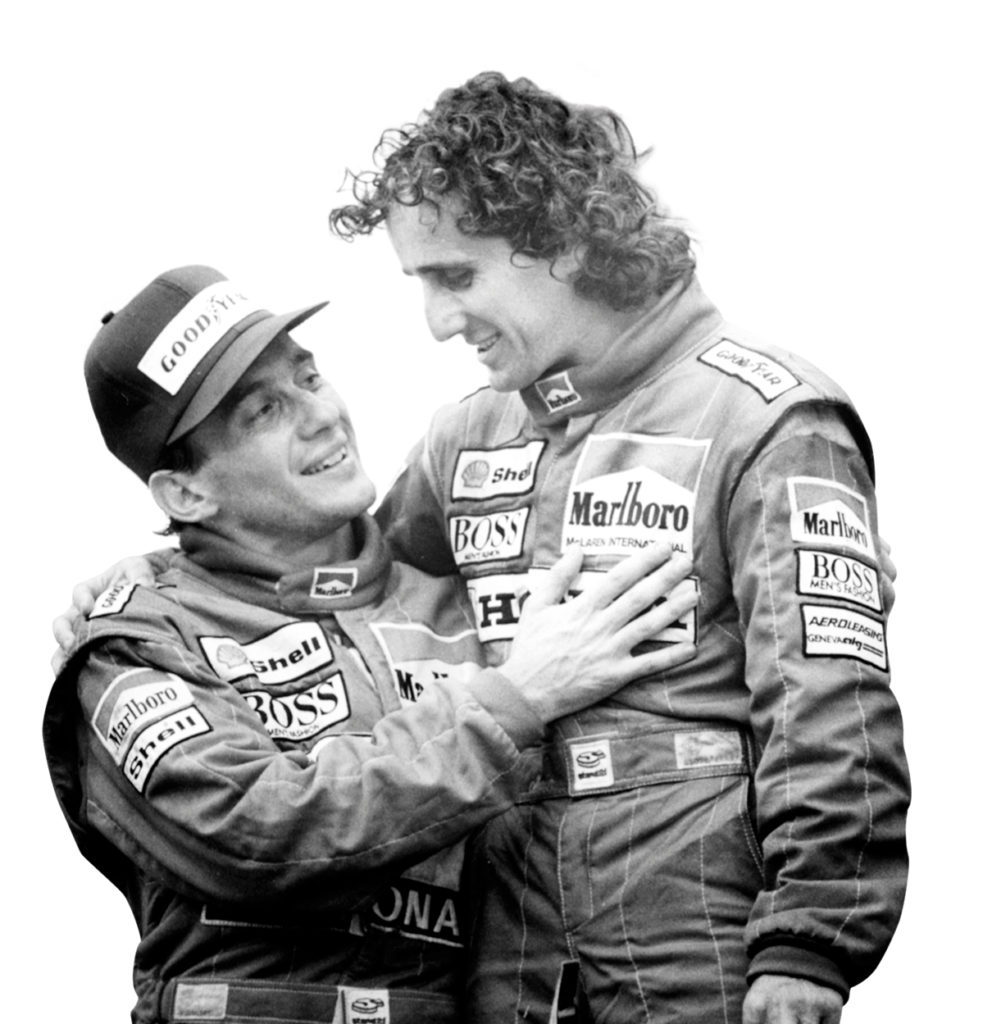

Prost nudges McLaren towards Senna and defines both drivers’ legacies

Stefan Johansson, with all due respect, wasn’t in the same league. If the new McLaren-Honda alliance wanted the best driver line-up for its first season in 1988, Alain Prost told Ron Dennis, sign Senna.

Secure as the team’s two-time world champion and F1’s clear benchmark performer, Prost believed he had nothing to fear from a man he knew was deeply ambitious and edgy. But he liked him – and respected his speed. And Honda loved him. It’s a stretch to say Senna joined McLaren because of Prost’s recommendation, but a blessing from the incumbent star sure didn’t hurt. Turned out Alain had played his part in unwittingly triggering the most turbulent, fraught and, yes, dangerous period of his life. Did the Senna rivalry define Alain Prost? It shouldn’t because there’s much more to this great racing driver – but ultimately yes, for most, it does.

1995

Mosley sells Ecclestone the bargain of his life

This deal was even better than buying Brabham off Ron Tauranac. Selling F1’s commercial rights on a 100-year lease for a one-off payment of just £240m? That’s a very nice bit of business – for Bernie Ecclestone. The rest of the movers and shakers in the paddock weren’t so impressed. But what did they matter? They’d be nowhere, and a great deal less rich, without the carefully crafted revolution orchestrated by Max Mosley and Bernie over the past couple of decades.

Anyway, who better than Ecclestone to run F1? He knew every dirty nook and cranny… The trouble was, their fiefdom duly diced, F1 was left open to be picked apart by private equity vultures. Something had to give in the face of European Commission pressure to avoid legal storms over alleged cartel management by a less than altruistic governing body and regulator. But really, these two between them had enough instinctive intellect to put cabinet ministers (or prime ministers) to shame. Was this deal the best they could come up with?

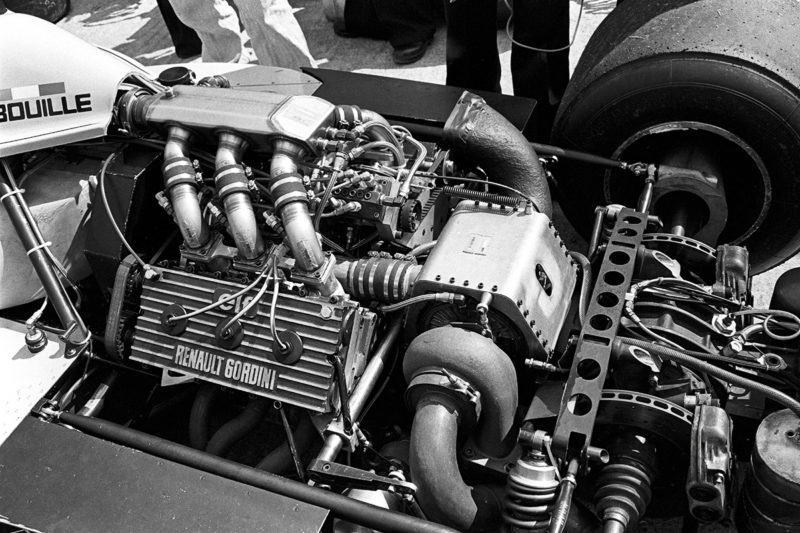

The turbocharged era in F1 began at the 1977 British Grand Prix with the ‘yellow teapot’ Renault RS01, driven by Jean-Pierre Jabouille

1977

British Grand Prix

Silverstone was due a calm weekend, in the slipstream of 1973 (when a multiple pile-up caused the British GP to be stopped and restarted) and 1975 (when a deluge caused most drivers to crash before the red flag appeared).

And indeed it was so. John Watson led for Brabham until his car failed – common occurrences, both – and James Hunt went on to take a popular home victory. So far, so straightforward, but this was a landmark race in several ways.

Renault had planned to make its Formula 1 debut in the French GP, but its ground-breaking RS01 – the first turbocharged entry in world championship history – wasn’t quite ready, so took its bow a fortnight later.

There is a case to be made for it not having been match-fit at Silverstone, either, as it came to a smoky halt after 16 laps, but within two years Renault would become a winner – and all teams subsequently jumped on the turbo bandwagon as reality bit.

Engineering innovation at Silverstone – the cast-iron 1.5-litre Renault Gordini EF1. Reliability problems were gradually ironed out

Why the decision to go with a turbo? Speaking to Motor Sport in 2014, development engineer Bernard Dudot said, “It was the best option available to us. We didn’t have the budget to develop a completely new engine, so had to take an existing 2-litre V6, from our sports car and F2 programmes, and modify it one way or another…” Ferrari cottoned on, as did other major car manufacturers such as BMW, Porsche and Honda. The superpower age had dawned.

Concurrent with Renault’s arrival, Michelin entered the world championship and became the first manufacturer to compete with radial tyres – another technical shift that would eventually be copied by all.

Last but not least, Gilles Villeneuve, right, made his F1 debut and might have finished fourth but for an unnecessary pitstop triggered by a faulty temperature gauge. It was a race that heralded two significant innovations and a new cult hero.

1979

Daytona 500: NASCAR goes live

Nowadays, as in Formula 1, saturation coverage means little is missed in NASCAR, but it wasn’t always so. The 1979 Daytona 500 was the first NASCAR race broadcast live and in full on US TV. Already the most successful driver in Daytona history, with five wins, Richard Petty extended his record to six – but only after inheriting the lead when Cale Yarborough and Donnie Allison collided while duelling for victory on the final lap. After their cars came to rest, the battle continued with fists and the TV cameras captured the moment. Allison’s brother Bobby became embroiled, too, having stopped to offer his sibling a lift back to the pits.

Reflecting on the incident some years later, Yarborough said: “I think it made a lot of fans for the sport. It got people’s attention.” NASCAR had just become front-page news.

2009

Tragedy leads to the birth of the halo

In 2009, John Surtees’ 18-year-old son Henry was struck in the head and killed by a loose wheel at Brands Hatch. Just six days later, Felipe Massa was put in a coma after being hit by a flying spring in Hungary. These incidents kick-started a campaign to give drivers greater protection.

However, when the FIA introduced the halo in 2018 there was still a push-back. Max Verstappen claimed that the device was “abusing” F1’s DNA. The criticisms were silenced that same year at the Belgian Grand Prix when a pile-up saw Fernando Alonso’s McLaren launched over Charles Leclerc’s Sauber. The halo deflected the McLaren away from the head of Leclerc, saving his life.

Most recently it saved Zhou Guanyu during a crash at Silverstone this year, below. Some estimates put the number of drivers saved by halo as high as eight. Four years after its introduction, the sport would look very different without it.

8 times the halo proved its worth

1947

The bar room conversation that gave birth to NASCAR

It began in a rooftop bar at the Streamline Hotel, above, a short stroll from Daytona Beach, in December 1947 – a conversation between a group of like-minded individuals, spearheaded by Bill France. Originally from Washington, France had move to Florida during the 1930s and became very involved in the local racing scene. He wasn’t alone in feeling that the sport needed to be organised in a more professional way, to ensure regulatory consistency and to stop rogue promoters from absconding with gate receipts.

The National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing (NASCAR) would be inaugurated on February 21, 1948. It staged its maiden race in June 1949, at Charlotte, North Carolina. In Daytona, racing continued until 1958 on a course that combined the highway and beach. That ceased in 1959 when the Daytona International Speedway opened, and NASCAR took another stride towards becoming a national phenomenon.

2020

Esports goes mainstream

Nintendos and pixelated graphics. That’s all that racing video games were once known for. When the Covid pandemic hit, though, esports seized its moment to blast itself into the mainstream with the first F1 Esports Virtual Grand Prix on March 22, 2020.

The event saw the stars of F1, including Lando Norris, above, take to their home simulators to race one another while fans could log on and follow the action. But that was just the start: other series followed suit, racing and gaming fusing in a way that had been promised but had previously failed to deliver. As virtual events multiplied they attracted 26 million views worldwide.

This newfound exposure of virtual racing led to F1 Esports alumnus Cem Bölükbasi securing a seat in the 2022 Formula 2 championship. Popular YouTuber and sim racer Jimmy Broadbent also made a similar jump. After starting his career racing on a simulator in his mum’s shed, Jimmy now races in the Praga sports car series.

Sim racing now allows aspiring drivers to race on tracks from across the globe from home. While F1 drivers learn tracks online first. Gaming tech’s influence on racing is everywhere – and it’s only just getting started.

1980s

John Barnard’s lasting legacies

Every F1 car on the grid has two distinct features introduced at either end of the 1980s: carbon chassis and paddle-shift gearchange. And both were the brainchild of John Barnard, working firstly with McLaren.

“I needed maximum underwings,” he told Motor Sport in 2018. “I didn’t want to be constrained by the chassis, so needed that to be narrower… but that would cost torsional rigidity. A sheet-steel monocoque would be too heavy, but carbon was out there so I went to British Aerospace, which was making engine cowlings in carbon, and decided it was for me.” John Watson gave Barnard’s MP4/1 its maiden victory in the 1981 British GP.

Paddle-shift arrived eight years later, raced on the Ferrari 640. “It came from me hating the mechanical aspect of the gearshift,” Barnard said. “We had this horrible linkage running down the chassis, then I had to have a bump in the cockpit for the driver’s hand. How could I get rid of so much crap?” Very soon, all F1 cars would be this way.

Henry Ford

1963

Ferrari snubs Ford buyout, then pays the price

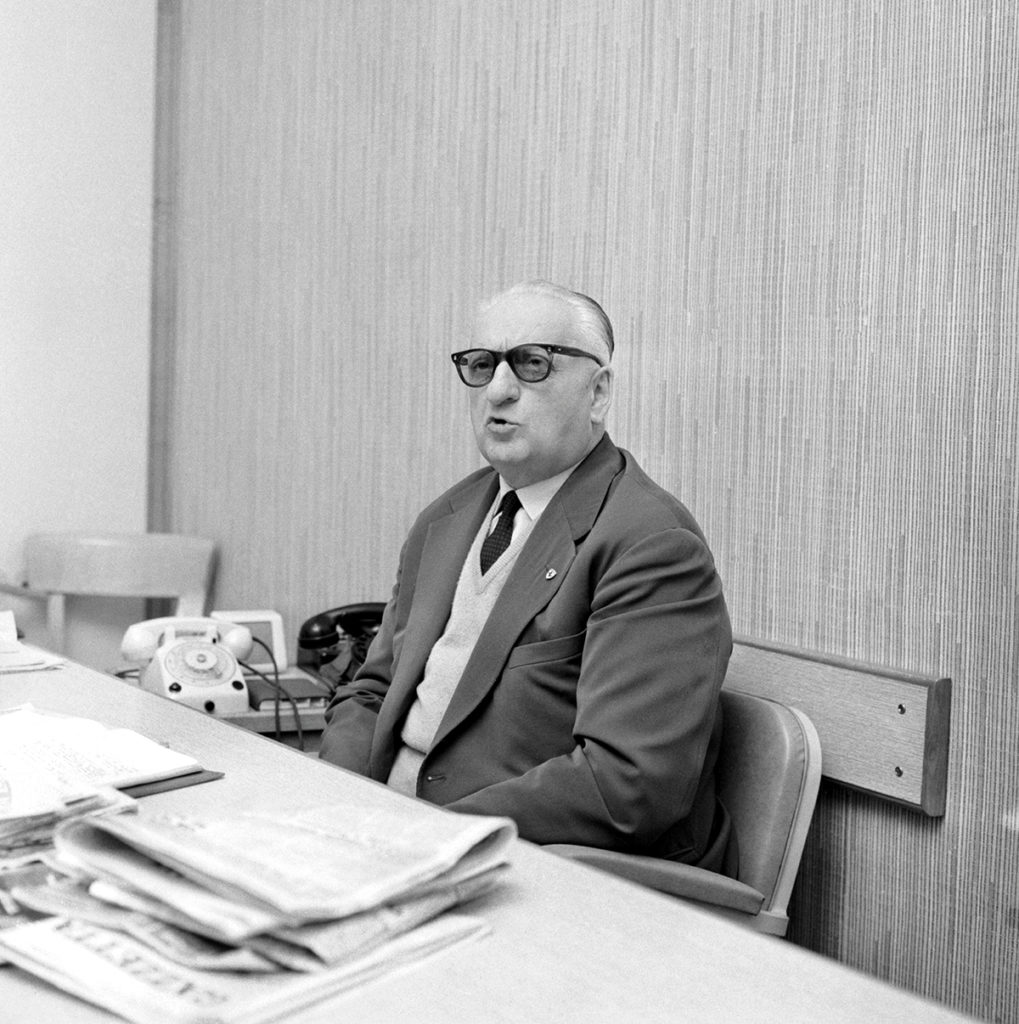

In Modena, Enzo Ferrari, below, right, was feeling the heat. Racing was all that drove him. The beautiful cars he built for the road? They simply financed the bit that counted. But for all the glories and growing aura, Ferrari was facing the unthinkable.

In Dearborn, Henry Ford II, above, was feeling the heat. Built on the shoulders of his father’s vision, FoMoCo was facing a slipping sales graph and growing aggravation from General Motors. He listened to the sell: motor sport could offer a lift – if only Ford had a sports car. So how about buying Ferrari? The arranged marriage made sense. If only this mismatched couple could rub along together. Following months of talks, Enzo eventually dismissed the negotiators with a flea in their collective ear. Give up control of his budget to go racing? That was missing the point. Slighted and personally insulted, Hank the Deuce was fired up for revenge – and his wrath took the form of the Ford GT40.

Over time, edgy Anglo-American alliances paid off. Ferrari, pressed to new extremes, won Le Mans for the final time in 1965 (only thanks to a dogged customer NART 250 LM driven by Jochen Rindt and Masten Gregory), before Ford’s revenge was complete – over four Ferrari-vanquishing years. Had Il Commendatore signed in his famous purple ink, Ferrari might have thrived under Ford – but it also might have died. Either way, its alchemical brew we cherish would have been diluted. Thank the devil Enzo kept his ink dry.

1967

Colin Chapman prises £100,000 from Ford: the DFV is born

During its golden spell in the early 1960s, Lotus had been one of many teams relying on Coventry Climax as a motive source. When the engine regulations changed for 1966, however, doubling maximum capacity from 1.5 to 3 litres, Coventry Climax decided not to continue with its grand prix programme.

Lotus swapped and changed during the season, using Climax and BRM units bored out to 2 litres, plus BRM’s 3-litre H16 (science remains powerless to explain how Jim Clark won the United States GP with that), while boss Colin Chapman worked behind the scenes to find a solution.

Former Lotus employee Keith Duckworth agreed that his fledgling engineering firm Cosworth – set up with Mike Costin – could do the job, so long as a £100,000 development budget was provided.

Aston Martin and Ford spurned Chapman initially, but he subsequently went back to the latter – this time approaching via Ford UK’s PR chief Walter Hayes, with whom he had a strong relationship.

Thus were the wheels set in motion. Ford in Detroit eventually signed off the deal and the Cosworth DFV (Double Four-Valve) turned grand prix racing on its head.

Jim Clark (Lotus 49) gave the DFV a winning debut in the 1967 Dutch GP; by the time Michele Alboreto (Tyrrell 011) had taken the chequered flag in the 1983 Detroit GP, the DFV had recorded 155 Formula 1 World Championship grand prix victories, played a key role in the acquisition of 22 world titles (12 for drivers, 10 for constructors), notched up F1 successes with 12 manufacturers – Lotus, Matra, McLaren, Brabham, March, Tyrrell, Hesketh, Penske, Wolf, Shadow, Williams and Ligier – and powered two Le Mans winners.

It has no peers. It’s notable how little direct influence Ford had on its major contributions to most of its key motor sport game-changing. Beyond paying the bills, of course, and even here UK PR boss Walter Hayes deserves the credit for recognising the value in the pitch from Chapman for that £100,000.

Cosworth DFV: racing’s greatest engine

1911

Indianapolis 500, racing’s greatest spectacle, is born

Opened in 1909 – when the first event it hosted was the start of a hot-air balloon race – the Indianapolis Motor Speedway had been beaten into existence by the Milwaukee Mile (1903) and Brooklands (1907), but was swift to establish its credentials.

Indy hosted a number of race meetings during its first two years of existence – and progressively dwindling crowds led officials to wonder whether this had been too much of a good thing.

For 1911, they decided to run a single headline event with a major purse – and settled on a race distance of 500 miles.

One car stood out on the 40-car grid – the Marmon Wasp, above, of factory engineer Ray Harroun, the only driver to take the start without a riding mechanic. Instead, he fitted a rear-view mirror in order to keep an eye on events in his slipstream – the first time one had been fitted to a racing car.

The grid was settled by the order in which entries were received by post. Harroun lined up 28th and gradually worked his way to the front. Relief driver Cyrus Patschke took over for 35 of the 200 laps, but Harroun handled the rest and went on to win in a time of 6hr 42min 8sec. He took home $14,250 in prize money – almost three times as much as runner-up Ralph Mulford – and, having come out of retirement for the occasion, announced that he would be quitting once again.

The Italian Grand Prix has been staged more often than any other such race and the 2022 event will be the 92nd since 1921. This year’s Indianapolis 500 was the 106th…

The greatest Indy 500 finishes

The success of the Lotus 79, pictured, in Mario Andretti’s title-winning season had its roots in the 78’s aero efficiency

1977

Lotus 78 wing cars take off and brings aero to F1

The Lotus 79 tends to hog the limelight, as the first ground-effect car to lift the F1 World Championship, but its domination owes much to its forebear.

The idea of creating ‘negative lift’ – downforce – by running air through sidepod venturis had actually been explored the previous decade by designer Tony Rudd and aerodynamicist Peter Wright at BRM. The project was some way from fruition when higher authorities at BRM pulled the plug.

By the mid-1970s Rudd (left) and Wright were both at Lotus, where Colin Chapman had been harbouring similar thoughts. As Wright said to Motor Sport (May 2000), “We ran a Renault 4 van around Hethel and hung stuff off the back to test it out. When we looked into it further, we found if you put skirts on the sidepods to seal the venturi off, then it really worked spectacularly. I knew it was going to be good when in the wind tunnel it sucked the revolving floor up!”

Mario Andretti won four grands prix with the Lotus 78 in 1977 – one more than that season’s champion Niki Lauda – and the car scored further victories at the start of ’78, one apiece for Andretti and Ronnie Peterson, before the 79 made a winning start in the American’s hands in Belgium.

Aerodynamic efficiency has been at the core of racing car design ever since.

1966

Belgian Grand Prix: dawn of Stewart’s safety crusade

Only 15 drivers started the second F1 World Championship race of the new 3-litre era – plus Phil Hill in a camera car, doing some filming work for John Frankenheimer’s Grand Prix – and more than half had disappeared before a lap was run. Jim Clark’s engine had blown, but the rest had either spun off or crashed, having been caught out by a downpour.

Having encountered a river running across the circuit close to the Masta Kink, Jackie Stewart lost control of his BRM, clipped a telegraph pole and demolished a hut before coming to rest. The Scot was trapped in his bent chassis and soaked in fuel, but there were no marshals to be seen.

Fortunately, fellow drivers Graham Hill and Bob Bondurant had also left the road and came to Stewart’s rescue – once Hill had borrowed a spanner from a spectator. After finally being transferred to the circuit medical centre, and being left on the floor on a stretcher, he found it short on doctors but high on cigarette butts. He was subsequently transferred by road to hospital in Liège, whereupon his driver got lost after failing to keep pace with his police escort.

It was the day that set Stewart on a course to improve circuit safety and medical facilities, which put him at loggerheads with some in the sport. It would also be the last time he started a race without a spanner taped to his steering wheel.

Jackie Stewart talks to Alan Henry

1992

Soper punts the BTCC into a golden era

This single-class 2-litre idea was catching on. Banishing the hairy Sierra Cosworth RS500s seemed like a crazy idea and yes, we’d always miss them. But these ‘rep-mobiles’, they were racy and the manufacturers were flocking in. Now what’s this? A nail-biting title encounter on the Silverstone GP circuit decided by a BMW punting out a Vauxhall, thus making the driver of another BMW champion? It was all kicking off.

Steve Soper and John Cleland made peace and quickly came to terms amid the storm they’d kicked up. It wasn’t pretty.

But just look at those TV figures. And how the crowds were streaming into the gates of British race tracks, just like they used to. The British Touring Car Championship – the best motor sport circus of the 1990s? You better believe it.

1971

Ecclestone buys Brabham at a steal

On a yacht in Monaco, Ron Tauranac shook hands on a deal to sell the team he co-founded. It was a handshake that had massive repercussions. Bernie Ecclestone was just what the team needed – but he was just what the whole of Formula 1 needed, too. Give him time.

Tauranac recalled agreeing to £130,000 to hand over Brabham, based on ‘asset value’. But at the 11th hour Ecclestone dropped the offer to £100,000; Ron rolled over. He stayed for a while longer, as an employee, as Ecclestone forged ahead into a commercial decade, but the arrangement was never going to last. Setting up Ralt better suited Tauranac – as Ecclestone, at Brabham, began to shape F1 in his own image.

1976

Fan power takes on the F1 establishment

The blazered officials were adamant: James Hunt would not restart the British Grand Prix. But resentment was boiling over among the crowd. Booing? Throwing cans on the track? You didn’t get this at Brooklands… Times had changed and F1 was moving with it. Fearful of a riot, the rattled officials relented, Hunt took the start (in his repaired race car), passed Niki Lauda and won. In a year pitted by volatile recrimination, Lauda’s fiery Nürburgring accident – and a British GP disqualification more than two months after the event – the rivalry stoked between the two ex-flatmates captured the attention of the world, as fans new and old tuned in to a live broadcast of the sodden Fuji finale.

Spurred by the boom, the BBC began formalising plans for its grand prix highlights show. Every race would soon be on the box regularly and for the first time.

1999

Audi heads for Le Mans

Vorsprung durch Technik. It conquered rallying in the Group B era, and Quattro know-how blazed a trail through touring car racing in the 1990s. So what next for Audi?

Sports car racing and Le Mans was where Audi believed it could best express itself. The hard-top R8C born in the UK versus Joest’s R8R spyder (both below) fell well short, but the Four Rings nailed the brief at a second time of asking. The R8 won four of the next five Le Mans, before Audi had the audacity of pursuing a whispering turbo-diesel dream.

The R10 won first time out in 2006. As harnessing hybrid technology became the next endurance racing grail, Audi stamped its mark on the long game: between 2000 and 2016, when it took a final bow, 13 victories at the Circuit de la Sarthe made the race and brand synonymous. Who needed F1?

The engine guru behind Audi’s success

2005

F1’s American dream turns into a nightmare and takes a generation to recover

Caesars Palace car park; sweltering Dallas; Motown proving not in tune; the non-events in Phoenix… After that, F1 waited nine years to find a US home, and landed on the obvious: where better than the venue of the Indy 500?

It was all going so well until 2005, above, when Michelin provided tyres that were not up to the job. Accountability was shared, even if only Michelin took the rap, as F1 spiralled into farce. The teams running the offending rubber were left with little choice but to park at the end of the warm-up, leaving a pair of Bridgestone-shod Ferraris, Jordans and Minardis to ‘race’ – as boos rang out.

F1 returned to Indy twice more, but the damage was done. Amazing how F1 in the US has recovered (thanks Austin and Netflix).

The one man cheering at the 2005 US GP

2017

F1 gains Liberty as Bernie bows out

Ecclestone again? That’s the power of the man… When the dice finally rolled against him and F1 bid a happy farewell to cold private equity indifference, Ecclestone’s time at the helm was also up. Some might argue control by an American media empire is barely a step up from the CVC days of avarice, but let’s give due credit: Under Liberty, F1 has been let off the leash. The Bernie model of operations peaked in the mid-90s then stopped evolving.

Ecclestone’s contribution was immense but Liberty’s suits are taking care of business. What happens now may colour the next chapter of our pivotal points in motor sport. Under a new regime, there’s discontent growing between an increasingly hard-line FIA and an unimpressed promoter. Accords in motor sport have a habit of not lasting long; in that respect, some things never change.

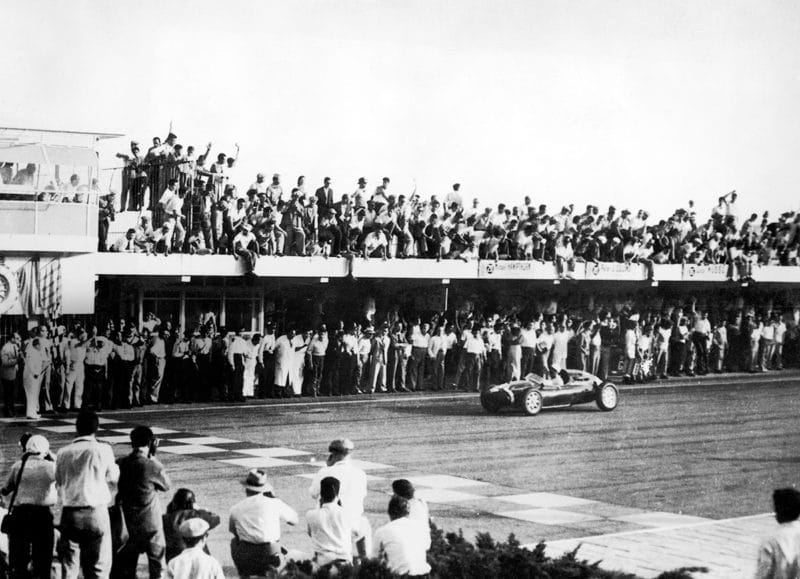

Stirling Moss ushers in a new era at Buenos Aires in Rob Walker’s mid-engined Cooper T43

1958

Argentine Grand Prix – the first world championship win for a mid-engined car

Cooper had been part of F1’s fabric through the early years of the world championship, but its first appearance was a quirky cameo. American Harry Schell entered his mid-engined Cooper T12 F3 chassis for the 1950 Monaco GP, albeit with an 1100cc JAP engine rather than its customary 500. Its unsuitability for purpose was never established; Schell was one of several drivers eliminated in a first-lap pile-up, but it was a pointer to the future.

The 1957 Monaco GP marked the first serious entry for a mid-engined single-seater Cooper – and Jack Brabham looked set to finish third until his engine cut out, the Australian pushing his T43 to the line.

Less than a year later, with his factory Vanwall not ready for the opening race of the 1958 campaign in Argentina, Stirling Moss switched to Rob Walker Racing’s Cooper T43 and beat the more powerful Ferraris (to which he conceded 600cc, two cylinders and about 100bhp). There was some subterfuge – Moss’s pit continued to indicate that he’d need fresh tyres, but it was a stop he’d never intended to make if he was to maintain hopes of victory. As he recalled in 2008, “The kerbs were very low at some points and, where possible, I was deliberately running onto the grass in an effort to cool the tyres. I could see that the fronts had worn down to the canvas.”

The Ferrari drivers upped their pace once they realised Moss’s game, but it was too late: he was 2.7sec clear of Luigi Musso at the flag.

It wasn’t the first win for a mid-engined car – Auto Union had several in the 1930s – but it was the first of the new era. Brabham took the title in 1959 as the mid-engined revolution accelerated. Moss became the last driver to win an F1 race with a front-engined car – a Ferguson at the 1961 Oulton Park Gold Cup.

1978

Professor Sid Watkins meets Bernie Ecclestone and transforms track safety

It was in 1978 that Bernie Ecclestone requested an appointment with Professor Sid Watkins, left, head of neurosurgery at the London Hospital, to discuss a health matter. But there was an ulterior motive…

Ecclestone wanted to improve medical facilities at grand prix circuits – and to keep them consistently high. Watkins had ample experience of working in the sport and agreed to come on board.

The 1978 Italian GP would be a significant turning point in terms of medical care. During his first few months in the role, Watkins followed events from race control. After a start-line pile-up at Monza, it took him a while to get through the throng and he arrived just as Ronnie Peterson was being loaded into an ambulance. The Swede had multiple leg fractures – and subsequently suffered complications that claimed his life.

In his Motor Sport lunch with Simon Taylor, Watkins said: “I felt that the initial response had been a shambles. Reports of how long it took for the ambulance to reach the scene ranged from 11 to 18 minutes. I agreed with Bernie that I was going to have to take a much more active role. I wanted to be in a car, with life-saving equipment on board, to get to an accident in the shortest possible time, and run behind the field on the first lap.

“We had this two weeks later at Watkins Glen, an estate car with no rear seats, me in the front and the anaesthetist, Peter Byles, sprawled on the floor in the back. The driver allocated to us was sweating heavily, and obviously nervous. When the race started he set off in vain pursuit, hit the kerbs at the chicane and took off, landing very forcibly. We managed half the lap before peeling off, and just reached the medical centre before the field, led by Andretti, caught us. After that Bernie made sure we had a proper car and a proper driver.”

Jackie Stewart had done a great deal to improve safety during his racing career; five years on from the Scot’s retirement, Watkins took things to the next level.

Roebuck’s legends: Sid Watkins

1980

Audi triggers a four-wheel-drive rally revolution

It’s hard to imagine, but Audi didn’t have much of a competition pedigree in the late ’70s.

It was the Quattro that established Audi’s sporting credentials and set the company on a course that would embrace success in touring cars, endurance racing and, crucially, no-holds-barred rallying.

Four-wheel-drive cars weren’t initially permitted in the WRC – not that it mattered, because no volume manufacturer produced one. The FIA relaxed its rules and admitted 4WD from 1979, with Audi unveiling its Quattro at the 1980 Geneva Motor Show.

The car scored a debut victory at the 1981 Jänner Rallye in Austria, and notched up its first WRC victory soon afterwards – Hannu Mikkola in Sweden.

But it was the following year when the all-wheel-drive tech combined with the Group B regulations that it came into its own. Michèle Mouton came close to taking the WRC title for Audi in 1982, when the firm became champion manufacturer. Then Audi drivers Mikkola and Stig Blomqvist vanquished their rivals in each of the following two seasons.

The speeds of the fearsome Group B machines moved rallying onto a higher plane and captured the imagination of a new generation. And the Quattro was its emblem.

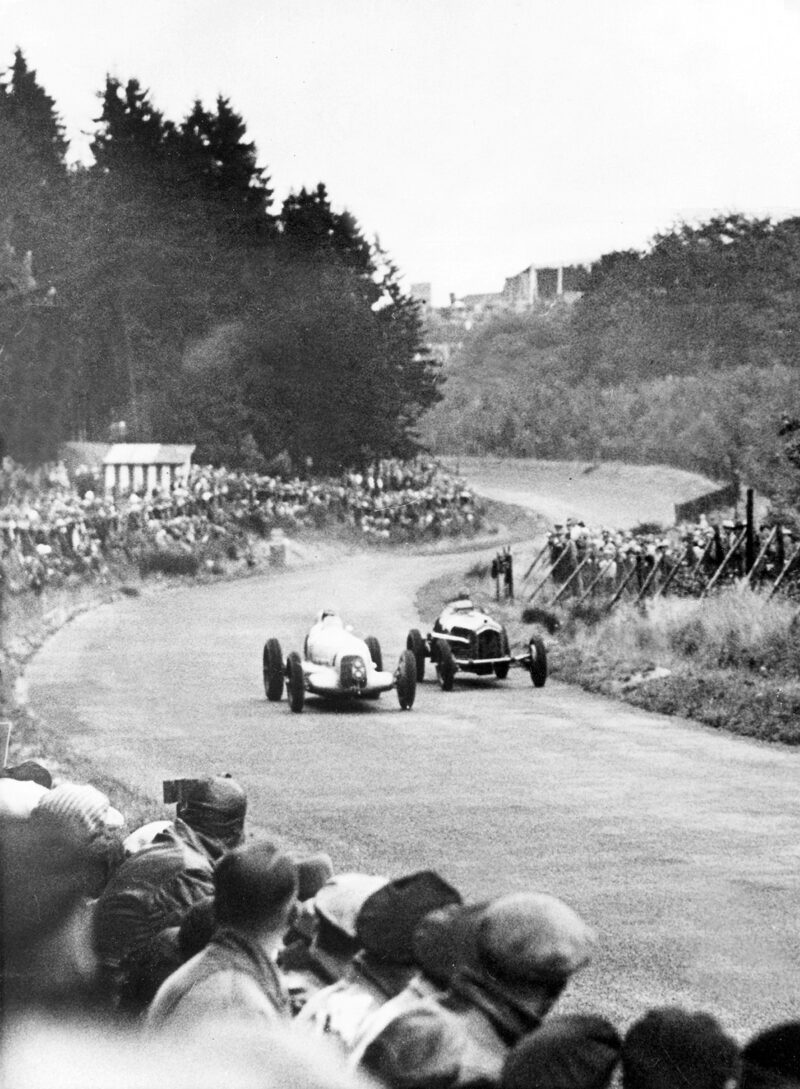

1932

Alfa Romeo P3: dawn of the grand prix car

In modern times, Italy’s national racing red – rosso corsa – has been corrupted by sponsorship decals and commercial considerations. It has always best been showcased by cars of yore – the Maserati 250F, perhaps (in period spec, no roll hoop), or this, Alfa Romeo’s ground-breaking P3, or Tipo B.

An elegant supercharged straight-eight from the drawing board of Vittorio Jano, the P3 was the first true centrally single-seated grand prix car – a concept that survives to this day, no matter how different the cars might look… or sound.

Introduced in 1932, it won all three of that season’s major grand prix events, Tazio Nuvolari triumphing in Italy and France, with Rudolf Caracciola doing likewise in Germany.

Financial concerns forced Alfa to abandon its racing plans in the early part of 1933, but the emerging Scuderia Ferrari managed to negotiate use of some P3s in the final phase of the year and took a clutch of victories, including the final two grandes épreuves in Italy (Luigi Fagioli) and Spain (Louis Chiron).

The 1934 campaign heralded the arrival of Germany’s state-funded Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union teams, who would soon introduce hitherto unseen levels of performance to the sport, but the P3 remained the most successful car and Achille Varzi scored six significant wins at its helm.

Vittorio Jano’s P3 was a revelation in 1932 but by the 1935 German GP, above, Auto Union and Mercedes had gained the upper hand. Despite this, the Alfa stunned at the Nürburgring

One of its finest victories, however, was saved for late in its career. Mercedes-Benz won five of seven European Championship races in 1935 and Auto Union one, but they were to be vanquished on home soil at the Nürburgring by Tazio Nuvolari in his notionally obsolete P3.

Manfred von Brauchitsch had led comfortably for Mercedes at the start of the final lap – but Nuvolari had been forcing him to maintain such a pace that the German suffered a blown tyre.

As reported in the September 1935 Motor Sport, “It had been a memorable race and the sight of Nuvolari hanging on to the Merc for lap after lap, with a car 20mph slower, is one that will live in the memories of all who were fortunate enough to be present. Nuvolari is the master.”