Top Le Mans moments 30-21: Audi makes its debut and Ford beats Ferrari

A series of era-changing events in these momentous snapshots from Le Mans: Audi makes its debut, Richard Attwood wins in the Porsche 917 and Ford beats Ferrari… in 1964

30 – 1999 Audi takes its bow

Flying Mercedes stole the headlines, BMW scored its one and only Le Mans victory and Toyota’s handsome GT-One once again fell short. But the somewhat muted presence in third and fourth had greater significance for what came next over the following decade and more. Audi hedged its bets with the open-cockpit R8R and British-built R8C coupé that first time out, and it was the former that stuck, to put in a stealth-like run to the podium. The experience laid the foundations for Audi’s incredible run of 13 wins from the next 15 races.

29 – 1970 Attwood’s safe choices pay off

He’d lost the 1969 race from a six-lap lead more than 20 hours in when the gearbox broke. This time Richard Attwood was taking no chances with Porsche’s potent 917: he chose the unfancied 4.5-litre flat 12, a short tail and in Hans Herrmann, an ageing co-driver who had first raced at Le Mans in 1953. Around them six of the eight 917s retired, as did nine of the 11 Ferrari 512Ss – and Attwood/Herrmann led all the way from 2am. Porsche had won Le Mans.

Just not the one everyone was expecting.

Few would have bet on Attwood and Herrmann’s Salzburg red Porsche 917 coming out on top of the 1970 field, but they pulled off quite the historic coup

DPPI

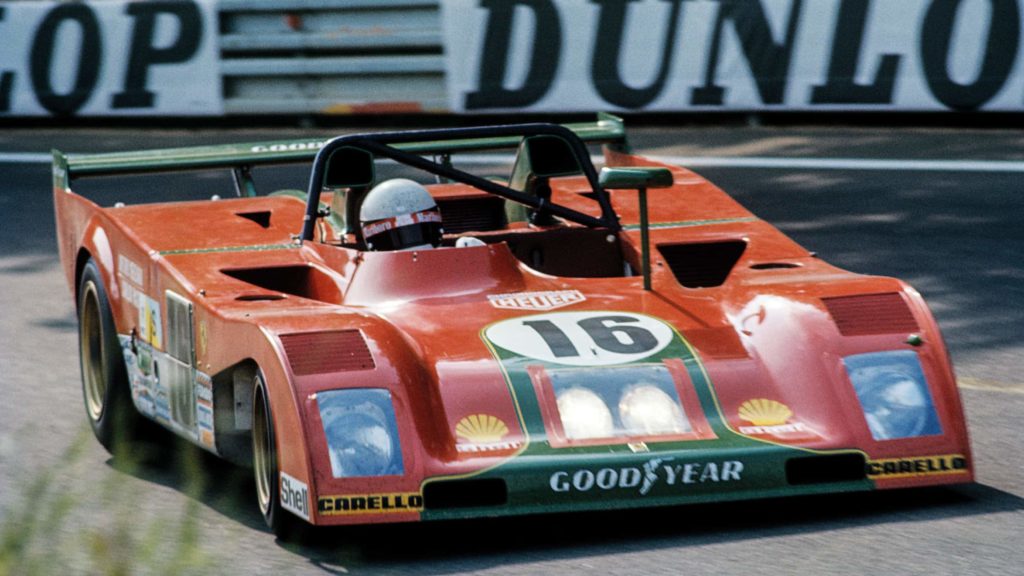

28 – 1973 Ferrari closes its sports car programme

Enzo was poorly. Long-time designer Mauro Forghieri was sidelined. And Ferrari’s F1 programme was a shambles. Its sports cars were better, but still Matra had beaten it at Le Mans and in the world championship. Fiat’s money would only go so far. So something had to give at Maranello. It was a closely run thing, but F1 – given new focus by the arrivals of Luca di Montezemolo and Niki Lauda, plus Forghieri’s return from the wilderness – got the nod.

27 – 1969 Sliding doors for Pescarolo

On a Wednesday morning in April 1969, the Mulsanne had been closed to road traffic so Henri Pescarolo could test a dramatically-shaped MS640 coupé. He was still warming up the car when it took off. It exploded on landing. “I was strapped into the burning wreck,

fully conscious,” Pescarolo told us. “The pain when your body is on fire, I cannot describe. I didn’t know how to get out.” But he did, recovered and strapped in – to become France’s greatest Le Mans hero.

Pescarolo watches the 1969 Le Mans 24 Hours from his hospital bed. He’d return to rack up four wins and a record 33 starts

Getty Images

26 – 1927 Wipe out at White House

Three works Bentleys were entered for Le Mans in 1927. That night all of them got tangled up in the same accident at the infamous White House Corner (aka Maison Blanche, to the locals).

One was able to extricate itself, but was badly damaged with a bent chassis, cracked steering ball joint and only one functioning headlight. It was patched up as well as was possible and returned to the fray. It retook the lead in the final hour, the rival Aries then retiring leaving the battered Bentley to somehow win by a record 20-lap margin (349.808km) that still stands to this day.

25 – 1988 Dorchy’s WM hits 400kph

When Roger Dorchy hit a new record speed in excess of 250mph on the Mulsanne in 1988, no one could have known it would effectively be set in stone inside two years. By 1990, the near four-mile drag of public road, correctly called the Ligne droite des Hunaudières, would be dissected by a pair of chicanes and the monster speeds a thing of the past.

The chicanes weren’t a reaction to the big numbers being achieved on the straight in the late 1980s, mostly by the little WM team for which Dorchy drove (see #23). Made up mostly of Peugeot engineers pursuing their passion out of hours, WM made it its business to try be quickest through the speed traps each year and then embarked on Project 400, an attempt to push the record through the 400km/h barrier.

Dorchy’s record will no doubt stand forever. It is listed in the history books at 405km/h (252mph), though he actually achieved 407km/h. WM’s links with Peugeot resulted in the former figure being declared in the year of the launch of the French manufacturer’s 405 saloon.

Yet the highest speed ever achieved on the Mulsanne might be higher still. Vincent Soulignac, technical director at WM, told Motor Sport three years ago he was confident that the previous iteration of the team’s Group C car had been nudging 420km/h in 1987. The radar system in place was subsequently found to be incapable of measuring the kind of speeds the P87 was hitting.

24 – 1990 Blundell’s banzai pole lap

How the straight-line speed record would have evolved had the chicanes not gone in can only be a matter of conjecture. Dorchy’s WM-Peugeot P88 had around 900bhp and a super-slippery shape. Two years later, Mark Blundell’s Nissan R90CK had in excess of a 1100bhp and much more downforce, yet according to the team’s data, the car still hit 237mph on one section of the straight on the lap that gave the Briton pole in 1990 by a full six seconds.

The R90CK wasn’t intended to have that much power. One of the wastegates on the 3.5-litre twin-turbo V8 jammed shut as the qualifying run commenced, sending the boost sky high. The top brass at the Japanese manufacturer wanted Blundell to abort the lap, but Nissan Motorsports Europe team manager Dave Price told his driver to push on.

Mark Blundell had eyes on an F1 career. But his big lap in the Nissan remains a calling card to this day

Getty Images

It was a wild ride, recalls Blundell: “The thing was spinning the wheels in fourth gear up to the Dunlop Curve. If you watch the on-board lap, you can see how vicious it was. And don’t forget those cars were the purest of the pure — a manual gearbox and no powersteering or traction control.”

The Nissan stopped the clocks at 3m27.020sec at the end of probably the most famous single lap in Le Mans history. Had Blundell been on qualifying tyres, then still part of the game at the highest level of sportscar racing, there could have been a few seconds to lose, and perhaps a few miles per hour to gain in top speed. It isn’t fanciful to suggest that the big-boost Nissan would have hit Dorchy’s speed record out of the park had there been no chicanes.

It is doubtful that anyone has got close to the kind of speeds Blundell achieved in 1990 in the 30-plus years that have elapsed. The fastest time through the official speed trap at Le Mans last year was a relatively modest 342kph (212mph) from one of the Toyota GR010 Hybrid Le Mans Hypercars.

23 – 1990 Chicanes added to the Mulsanne

A political football. That’s what the Mulsanne became in the on-off feud between Le Mans organiser the Automobile Club de l’Ouest and FISA, the sporting arm of the FIA.

What was then known as the World Sports-Prototype Championship had been relaunched at the end of 1988 by the FIA’s new vice-president of promotional affairs, one Bernie Ecclestone. He made an attempt – half-heartedly so, said some – to expand its exposure on TV, but the problem was that the ACO had its own media contracts and wasn’t about to relinquish them. That resulted in the French enduro being scratched from the world championship schedule in 1989.

Sacré bleu! The Mulsanne was cut into three by the insertion of two chicanes

Getty Images

FISA president Jean-Marie Balestre had an ace up his sleeve in the game of poker that followed. The Circuit de la Sarthe’s track licence was due for renewal at the end of 1989 and the fiery Frenchman pushed through a new rule limiting the maximum length of straights on an international circuit to two kilometres (1.2 miles). But, said Balestre, the Hunaudières could remain untouched if the ACO acquiesced over TV rights. It wouldn’t, and after Le Mans had again been removed from the WSPC, the ACO had no option but cut the Mulsanne into thirds with the two chicanes we know today in order for the race to go ahead.

22 – 2006 Loeb’s busman’s holiday

Safe to say Sébastien Loeb had never endured a recce quite like it. His Le Mans debut in 2005 was far from easy. Fresh from winning Rally Turkey in his Citroën, he jumped on a helicopter to La Sarthe for his first run in the Pescarolo C60 LMP1. Arriving at the track for the evening of the test day, he jumped straight into the prototype and headed out, in the rain, for his first laps of Le Mans. That year wouldn’t go Loeb’s way, with the car retiring after a crash, but his second shot in 2006 with France’s own Mr Le Mans, Henri Pescarolo, was one place short of a far higher entry in this list. Loeb, Éric Hélary and Franck Montagny were second, splitting the Audis.

21 – 1964 Ford’s first Ferrari revenge

Americans tend not to forget this one. Two years before 1966 and all that, and in the wake of the mess that was Ford’s aborted effort to buy Ferrari, the Blue Oval arrived at Le Mans in force in 1964 with its new GT40. It proved a disaster as gearbox failures and a fire meant all three failed to finish. But Ford had also supplied engines elsewhere that year, primarily to Carroll Shelby’s Shelby American Inc, which used a 4.7-litre V8 inside a Daytona Cobra Coupe. Dan Gurney and Bob Bondurant brought that car home fourth behind a trio of Ferrari prototypes – but as first GT, crucially ahead of the iconic 250 GTO.

Carroll Shelby, left, with the Daytona Cobra raced by Jochen Neerpasch, right. Bob Bondurant, centre, would finish fourth in Daytona No5

Getty Images