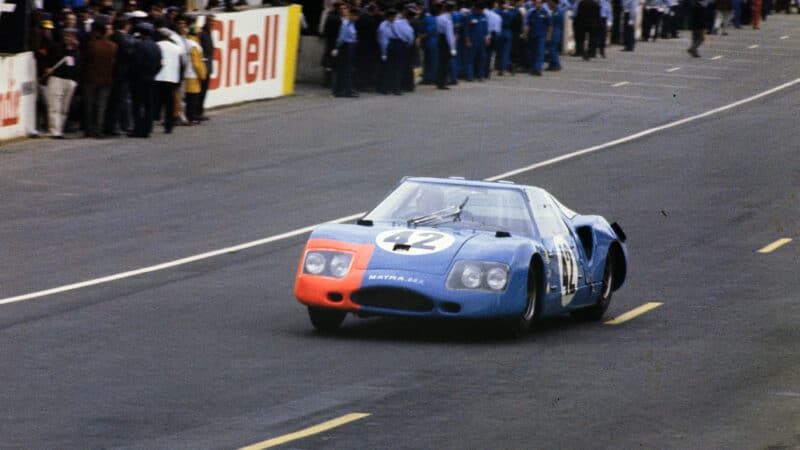

But Formula One came first. Through 1968 the Elf-backed F1 team ran the MS10 with Cosworth power under the Matra International flag, Stewart finishing second in the championship, and honed the promising V12 in the MS11. But it was mid-season before the MS630 received the endurance version, putting Matra at last into Division One at Le Mans. It was a hard blow when Pescarolo/Servoz went out with a puncture while lying second, particularly as the V12 did not finish a race that season an embarrassing contrast to Servoz/Gavin’s series of victories in the Ford-powered car.

However, Matra was fully committed to making a sports version work, and as Jackie Stewart amassed the seven Grand Prix victories which brought both driver and constructor titles for 1969, the prototypes tackled the endurance races with increasing confidence. A new spider, the chunky MS650, was developed from the 630, as well as a parallel design, the 640, with elongated low-drag bodywork for outrageous top speeds; but that was abandoned after it took off and destroyed itself while testing, putting Pescarolo in hospital for weeks.

Jackie Stewart, here at Zandvoort, delivered both F1 titles for Matra in 1969

Grand Prix Photo

This huge level of investment of funds and manpower could hardly be maintained by the profits of one specialist company, even with Elfs input, and in fact Matra was helped substantially by the French government. Thus it was able to send four cars to the Sarthe in ’69, and at last, at the place where it really counted, there was reason to wave the tricolor: the faithful Beltoise and Piers Courage were fourth, delayed by a collision after looking like winners, Guichet and Vaccarella just behind, and Galli and Widdows seventh. The impetus was building up, and an enthusiastic French public began to believe that ‘le bleu de France’ might after all pull it off.

Stewart’s wins, and Beltoise’s strong support, had come courtesy of Ford, as Matra `rested’ the F1 V12 during the ’69 season to redesign it. For 1970, designer Georges Martin gave it a magnesium instead of aluminium block, while a new top end brought narrower heads and central intakes, making for a more compact unit with power raised to 420bhp. Unfortunately it brought the worst Le Mans debacle so far – three engine failures one after the other. But aerodynamic lessons from the revised 630/650 were valuable, and the new lighter MS660 chassis, now a monocoque, did win the 1000km de Paris.

“Jabby Crombac said ‘this time we’re going to do it properly’”

After running three models in 1970, Matra sent only a single 660 for Amon and Beltoise to Le Mans in ’71, while preparing for next year the first without 5-litre rivals. Again a retirement – injection problems.

For 1972, with the F1 title ticked off from Lagardere’s battle-plan, that elusive victory at the Sarthe was top priority. The F1 team was reduced to one car, for Chris Amon, and staff reassigned to the now completely separate Le Mans team. No other sportscar races were allowed to dilute the effort – Le Mans was the sole target. To crew the three new 670s, backed by one of last year’s 660s, Ducarouge put an F1 driver in each, and widened the options by preparing two cars with new-spec 450bhp engines and two in older Grand Prix tune at 420bhp. In addition, two carried long-tail bodywork for peak Mulsanne speeds, while two went the short-tail high-downforce route. Surely this matrix of combinations had to throw up the correct solution.

Cevert in pits — huge ’72 effort boasted eight mechanics per car

Getty Images

It was an all-out effort, as Howden Ganley, then racing a BRM in F1, recalls. “Jabby Crombac approached me and said ‘this time we’re going to do it properly’”. And they did, with three full 24-hour tests for all the drivers. In addition, Ganley, a Le Mans novice, was taken to the circuit to drive the normally closed sections. Even the ACO was doing its bit in this enormous French effort.

The new MS670 was broadly similar to the 660, but with smaller front wheels and slimmer nose for better penetration. It was, says Ganley, a nicely balanced car which really handled well. Beltoise called it the best Matra of all.

When the great June weekend arrived, the scale and professionalism of the Matra corporation was obvious. The team numbered 120 people. Every driver had a Matra road car provided, and each crew had a separate trailer with their names on refinements unheard of then. The attention to detail, Ganley says today, reminded him of the tales of the legendary Mercedes operation of the Fifties. In the event, Ferrari withdrew his cars, so the aerospace-designed steamroller took charge: for many hours Pescarolo and Hill traded the lead with Cevert and Ganley. “We had agreed that we would be light on the brakes,” remembers Ganley. “Francois was nervous of driving with me – he thought I would be out to show him up. But we talked it out and I persuaded him I wanted us to win, and we could do it by staying off the brakes.”