Seeing no compelling reason why turbos could not be channelled similarly, however, FOCA kingpins Colin Chapman and Bernie Ecclestone had harnessed their Lotus and Brabham teams to boosted Renault and BMW horsepower.

McLaren and Williams followed suit and were primed to phase in deals with TAG/Porsche and Honda by the end of the 1983 season.

Turbo pressure was rising.

Development of the DFV had been piecemeal once initial glitches were fixed. No changes to ports, valve sizes or cams, never had there been any intention of building one-off screamers.

Why change a winning formula? Every GP of 1969 and 1973 had fallen to it after all.

DFV won on its GP debut with Jim Clark and Lotus 49 in Zandvoort, ’67

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

By 1975, however, constructors’ champion Ferrari’s flat-12 was topping 500bhp – at which point DFV had added 50bhp and 1500rpm to its original 408 at 9000 of 1967.

Demand had by now persuaded Cosworth to farm out kits and rebuilds to favoured sub-contractors, who in turn tuned and tweaked for individual teams seeking that extra 5bhp: Nicholson McLaren was the first to try shorter stroke/larger bore; and the rpm released by Swindon Racing Engines’ shorter inlet trumpets helped Shadow shine brightly but briefly in 1975.

Turbocharging steepened this steady curve – long before the sudden and late mandating of flat-bottomed cars for 1983.

Faced with the prospect of dragging a barn-door rear wing in compensation, Duckworth had to promise a shrinking customer base a minimum of 510bhp.

He put ambitious Mario Illien on the case.

Two cases, as it turned out.

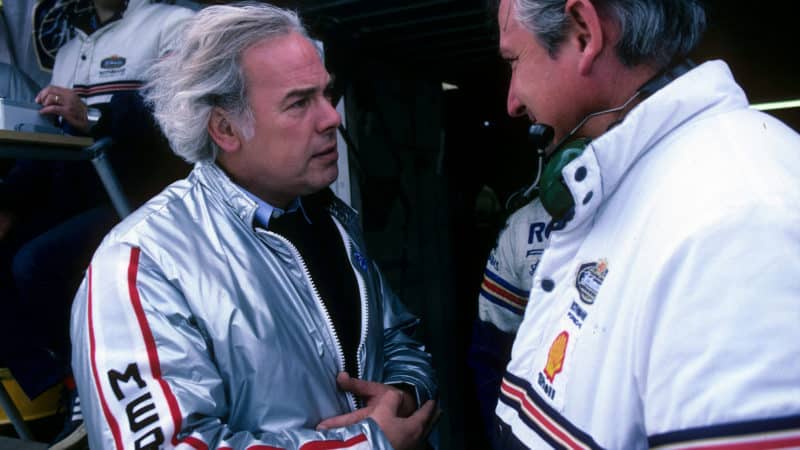

Keith Duckworth in 1983: under pressure to deliver more power

Thierry Bovy/DPPI

The first, an interim short-stroke DFV using the 90mm bore of its endurance cousin, arrived in time for the French Grand Prix in April.

The second was Illien’s ‘baby’. Delayed by internal politics – discontent sowing the seeds of Ilmor – DFY wasn’t ready until Spa-Francorchamps in May.

It blew up in morning warm-up.

This thorough reworking – block, sump, piston, liner, cam profile, throttle slides and manifolds – was most notable for redesigned heads: valves at an included angle reduced from 32deg to an asymmetric 22.5: that is, 10 inlet and 12.5 exhaust.

An increase in torque and 520bhp at 11,000rpm was claimed for a small reduction in mpg.

DFY’s improved drive made it well-suited to street circuits

Thierry Bovy/DPPI

McLaren and Williams purchased a few – but only Tyrrell bought into it: he ordered 10. Ken had relied on Cosworth for the entirety of his F1 journey since 1968: nine GP wins with Matra, one with a March, and 22 with cars of eponymous build; three drivers’ titles for Jackie Stewart, plus one constructors’ title and another by proxy.

“Cosworth always kept things very close to their chest,” says Lisles. “Ken believed in them and tended to go with whatever they gave him.

“I am not sure if DFY was any more powerful – maybe it was not even as powerful as the very best DFVs – and I don’t recall any extra revs; it had the same vibration problem in the valve-gear that DFV had.

“What it did give you was better drive at low revs. It didn’t have that ‘switch’ in its torque curve at about 6000rpm, so it was smoother and easier to modulate. That was helpful on any street circuit.