Despite or perhaps because of the torrential rain in Sicily that chilly Sunday, he was going great guns, driving faster than anyone, when he crashed into a ravine on a mountain pass near Caltavuturo. The motor sport journalist and author WF Bradley wrote: “Ascari’s car had fallen to such a depth that he and Mannini [Ascari’s riding mechanic] were not discovered until a search party went out when the race was over. They had been unable to climb out unaided, but they were not seriously hurt.”

Racing hacks were made of sterner stuff 106 years ago, for ‘not seriously hurt’ is not a description that we would use to describe their injuries today: hours after their accident Ascari and Mannini were taken to a small hospital in Polizzi Generosa, then, after a painful night there, they were transferred to a larger hospital in Palermo, where it was found that Ascari had suffered not only extensive bruising but also a fractured pelvis and a broken femur, and Mannini had snapped a rib and had dislocated his right shoulder. They both remained in hospital in Palermo for several weeks.

The 1919 Targa Florio had been won by André Boillot in a Peugeot – and, to the consternation of the Alfa Romeo formaggi grossi, none of their cars, driven by Giuseppe Campari, Nino Franchini, and Eraldo Fracassi, had even finished it. Ascari saw his chance, and he asked for two things: the right to sell Alfas across all of Lombardy, and the opportunity to race the company’s cars. Answers came back swiftly: yes and yes.

He won at Spa with authority, beating his team-mate by the thick end of half an hour

He raced for Alfa Romeo from 1920 onwards – at first shunting a little too often, but often placing well, yet scoring no wins – until, in 1922, he won the Coppa del Garda, between Gargnano and Tignale, which success cemented his promotion to the Alfa Romeo factory team for 1923, driving alongside his old pals Ferrari, Campari, and Ugo Sivocchi.

In 1923 he won his first major race, at Circuito di Cremona, a daunting course made up of 39 miles (63km) of dirt roads near Brescia. In 1924 he won the Parma-to-Poggio di Berceto hillclimb for the second time, and soon after that he won at Circuito di Cremona, also for the second time, now at the wheel of Vittorio Jano’s wonderful new Alfa P2, thrashing all the other runners by almost an hour, averaging 101mph (163km/h): heady stuff 101 years ago.

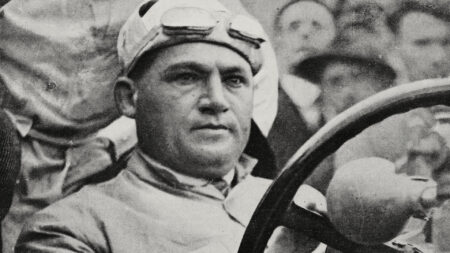

Ascari chases Segrave at Lyon in the 1924 French Grand Prix

LAT

He and his P2 then led most of the 1924 French Grand Prix, run on the tricky Lyon road course, losing the win to a mechanical failure with just three laps to go. Disappointed but undaunted, two months later, on a cold day in October 1924, he and his P2 utterly dominated the Italian Grand Prix. He started from the pole, he drove a fastest lap that would remain the Monza lap record until 1931, and he covered the 497 miles (800km) in a smidgen more than five hours, beating his closest challenger, Louis Wagner in another P2, by 16 minutes.

The following year, in June 1925, he won the Belgian Grand Prix at Spa with equal authority, this time covering the 503 miles (810km) in six hours 51 minutes, beating his Alfa team-mate and old chum Campari by the thick end of half an hour. Next up, in July, came the French Grand Prix at Montlhéry. Ascari, the form horse, was the pre-race favourite – which made Alfa Romeo team manager Nicola Romeo’s decision to give Campari the newest, lightest, and fastest P2 seem odd at best and unjust at worst. Ascari was furious, making his displeasure evident for all to see via the bizarre expedient of arriving at the circuit on race day unshaven, unwashed, and wearing dirty clothes deliberately selected for their scruffiness.

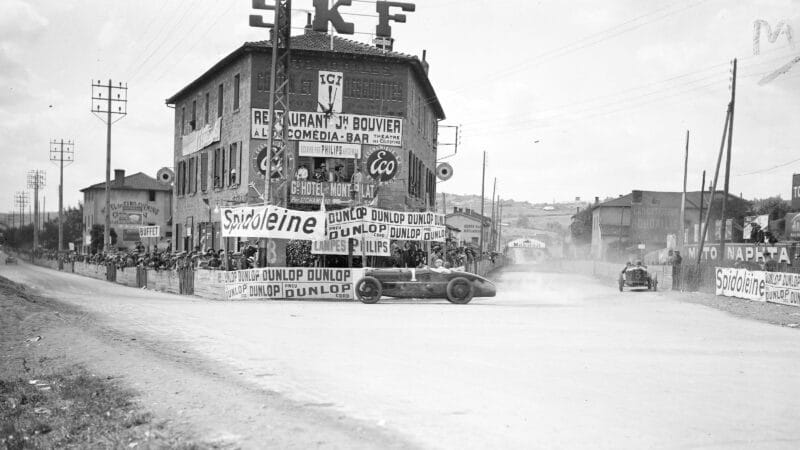

Start of the 1925 French Grand Prix: Ascari is already ahead of Segrave and closing on Pierre de Vizcaya’s Bugatti

Bettmann/Getty Images

Campari started second in the fastest P2, behind only Henry Segrave’s Sunbeam. Ascari began the race in sixth — but, even so, spurred on by righteous indignation, he had charged into first place by the end of lap one, and thereafter he left no margin anywhere, increasing his lead at every turn.

On lap 15 he stopped for fuel and tyres, and Jano warned him, “Vada tranquillo!” (go gently). But, despite the sudden arrival of a heavy shower, Ascari took no notice. He wanted not only to win but to win consummately, to make a statement and to show Romeo that he, not Campari, was Alfa’s main man. By the end of lap 22 he was in a commanding lead.