“When I eventually did some road racing, I took to it like a duck to water it was as if this was where I belonged. I guess that if I was a natural, that’s where it was. It certainly didn’t come that easy for me to do oval racing.”

Ultimately, though, Parnelli decided against accepting Chapman’s offer. F1, he pointed out, was more of a “gentleman’s sport” in those days. “It was starting to get professional, but it hadn’t arrived yet. And, to me, Indianapolis was far bigger.”

There was something else, too. Jones was well aware of the bond between Chapman and Clark. “I couldn’t accept being number two — not even to Jimmy. At Trenton in ’64 he raced the car that I’d won with at Milwaukee, and I was in the other Lotus. Chapman gave me a speech — ‘You know Jimmy’s our number one,’ sort of thing. In qualifying I set a new track record, and Jimmy was back in seventh, so then that kind of went away, and it was OK for me to do my thing. But I could see that if I went to F1, it was going to be a problem.”

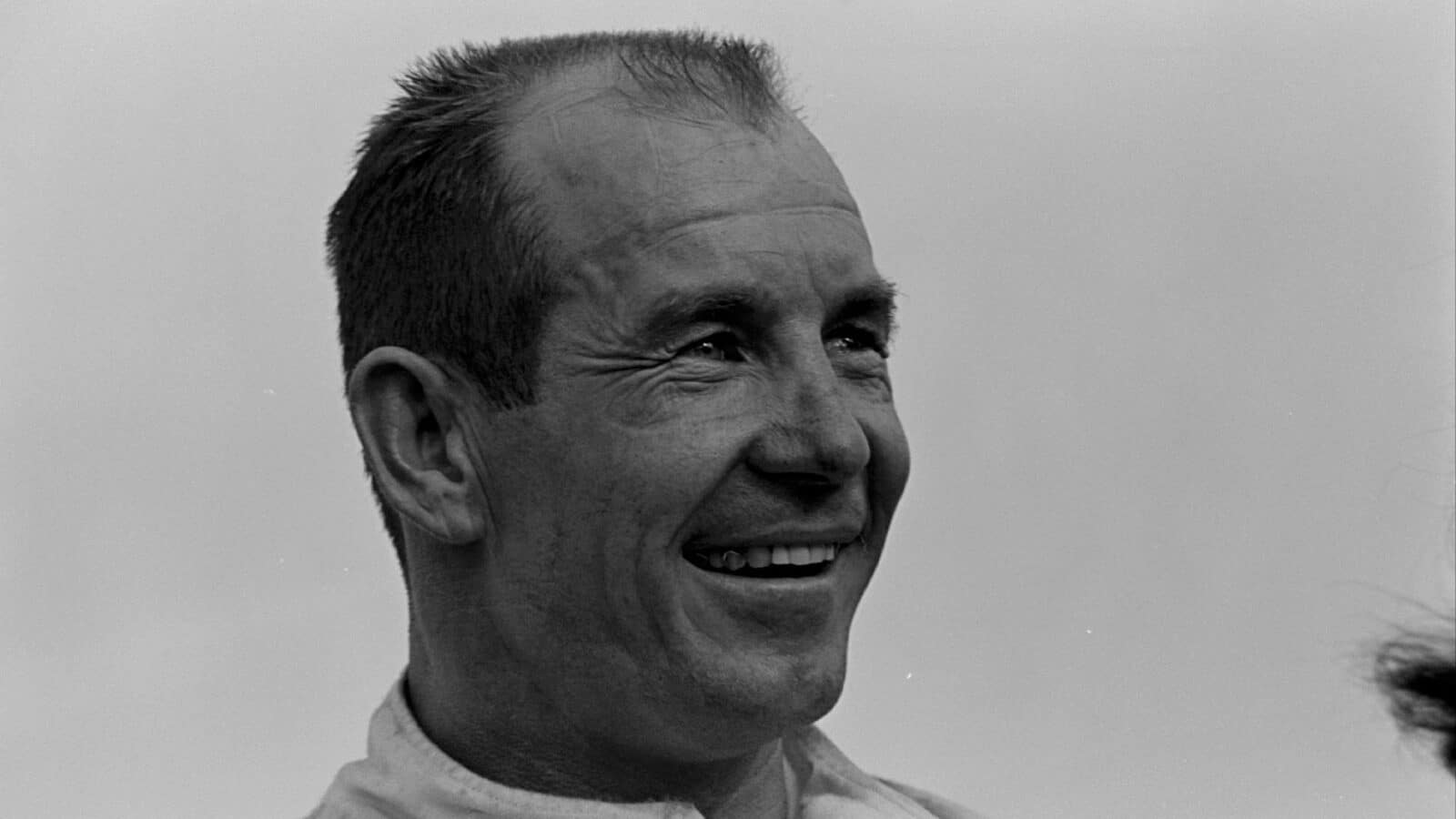

Jones decided to stick Stateside instead of pursuing a career in F1

Getty Images

An approach was also made by Enzo Ferrari, and Parnelli still chuckles at the Old Man’s financial offer. “To be honest I can’t remember what it was, but I know I laughed at the time. There was relatively little money in F1 back then, I was already past 30 and… I guess one of the reasons I quit racing early was that I’d burned myself out with all the travelling in my younger days.”

His younger days were generally fraught ones. The family was based in Torrance, California, in what Jones says was a rough neighbourhood. There was very little money around, and he had a hard-nosed approach from the beginning. Yes, he loved to race, but it was also his way out of poverty, and you got paid on results.

“The consequence of that was that I had tremendous desire. Coming from a poor family can do that to you. And when I started racing stock cars at 17, I certainly had a lot more desire than talent. I wrecked my car week after week, got into fights all the time, but eventually I began to win, and made it up through the ranks, to midgets and sprint cars.”

That was the route to Indianapolis, where every young driver wanted to be. Nowadays there is no logical link between racing a front-engined sprint car on dirt and driving a rear-engined Reynard at Indy, but Parnelli still thinks classic American short track racing is a great training ground. “It’s fantastic experience for any young driver, because it’s wheel-to-wheel racing. And because of that, you learn so much about where you can put yourself at high speeds.

“You’ve got to read the cars in front of you — not just the one right ahead, but all of them; if one of them gets in trouble, you’ve got to know where to go to keep out of it. It’s not just a matter of panic, and lock up, and slide into it. With that sort of training, you find out what you can get away with, and what you can’t.”

Jones’s era of sprint car racing the late ’50s and early ’60s is regarded by aficionados as the greatest ever. “I loved it,” he said, “But its scary to think about the cars we ran. No roll cages, just a little hoop behind you, no fuel cells, no proper belts — the first one I used was leather! It went around your waist, and over one shoulder.

“It was an unbelievably dangerous time, and a lot of guys bought the farm. At Daytona Jim Hurtubise went out of the track, and laid in a tree! He actually rode the tree to the ground, the car jumped off and the tree sprang back up again! Saved his life… I look at today’s cars and think, ‘Gee, if I’d had that much protection, I wouldn’t have had to lift at all!’”

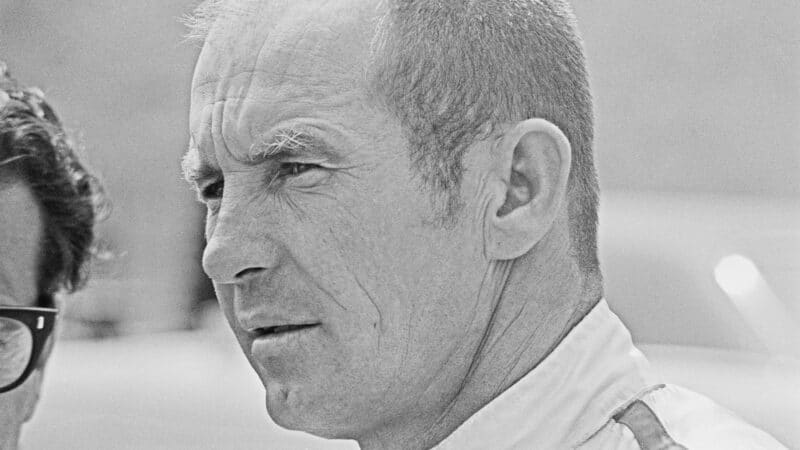

Jones celebrates his lone Indy 500 win in 1963

Getty Images

The record book shows that Jones won the Indy 500 only once, in 1963, although he smilingly points out that, four years later, he won the “Indy 495”, his revolutionary turbine-powered STP Oil Treatment Special retiring on lap 197, when a gearbox bearing failed.

Parnelli retired from the USAC Championship racing after that, but later formed his own team, which took Al Sr to two of his Indy 500 wins, and even ventured briefly into F1, with Andretti as driver.

Jackie Stewart well remembers his two Indy outings, in 1966 and ‘67. “When I raced there, of course, it was the time of the British invasion. Jimmy Clark and Graham Hill both won the 500, and people said it must be no big deal if the Brits could go over there, with no experience, and beat the Americans at their own game. And I think this attitude has stuck.

“I don’t believe, though, that any of us — not even Jimmy — ever drove particularly well at Indianapolis. We were successful because we had vastly superior equipment; we knew all about rear-engined race cars, but for the Indy establishment they were something from another planet.

“There is an art to getting around Indianapolis properly, and if you have it you don’t lose it. Look at the way Mario always went there, even well into his 50s. Still, I think the best I ever saw at Indy was Parnelli Jones. He was incredible; he drove like silk round there. It would have been fascinating to see him in F1…”