That karma reaped its reward when Jaguar’s lightning-quick D-type won the next three on the bounce. During which time only two works Ferraris finished. The best of them, however, was co-driven by one half of the partnership that would calm a chaotic Scuderia and make it whole at Le Mans: Olivier Gendebien. An ex-paratrooper, this cultured, wealthy Belgian rose above Enzo’s political peccadilloes to form one of sports car racing’s most cerebral and successful partnerships with Phil Hill.

Both men, the American more so, were frustrated by their lack of F1 opportunity at Ferrari – but Enzo knew they were a precious commodity: fast, reliable drivers who were mechanically sympathetic and capable of putting their egos in a box for the common good. He had them marked as sports car royalty and, Hill’s 1961 F1 world title notwithstanding, that assessment was correct.

In 1958, in a pontoon-bodied Testa Rossa that channelled rain into its cockpit, Hill drove without goggles at such speed as to cause team-mate Mike Hawthorn to marvel. Hill and Gendebien’s winning margin was 12 laps. They might have won the following year, too, were it not for a water leak with four hours to go while holding a four-lap lead. It was left to Ferrari’s Gran Turismo privateers to salvage third, fourth, fifth and sixth behind an Aston Martin 1-2.

By 1960 Enzo was insisting that GTs should become the race’s future but, of course, he continued to build prototypes that refused to be killed off by half-cocked rule changes regarding luggage space, turning circle and windscreen. Hill and Gendebien were split up for some unfathomable reason, but the latter won with fellow Belgian Paul Frère as Ferrari swept the board in the absence of Aston.

Enzo with sports car star Phil Hill

Getty Images

Jaguar had long ago withdrawn and handed responsibility to its privateers – the race had worked its magic in America – and Maserati was financially crippled. Le Mans had become a one-horse race. Not that it mattered, such was the mystique of plunging into the dark of dusk and beyond to emerge through the morning mist. Ferrari constructed fewer than 300 cars that year and half were sold in America.

His share of those proceeds gave Chinetti the money to go racing with his North American Racing Team. The Rodríguez brothers would be a thorn in the Scuderia’s side at Le Mans in 1961, ignoring all beseeching to slow down until a misfire ended a torrid 14-hour lead battle with the restored Hill/Gendebien.

Those rebellious young Mexicans were brought in-house for 1962 and Hill/Gendebien scored a comfortable victory, the last for a front-engined car. This signalled a sea change from without as well as within Ferrari. Gendebien retired forthwith and Hill, weary of the false fronts and backbiting, left the team at the season’s end. So, too, did eight disgruntled senior staff. Some of the latter returned, tails between their legs, but new blood was infused: Mauro Forghieri was made chief engineer at 28, and driver/engineer Surtees and engineer/driver Mike Parkes joined within weeks of each other. The Englishmen clunked rather than clicked but made telling contributions that guided the team through transition.

This, however, came as little relief to Enzo. Failing health and complicated home lives plus Italy’s troubled economy and troublesome unions had worn him down. That the annual production number had doubled was not entirely good news. Rushed cars, in jarring colours that were hard to sell, generated more complaints about dodgy electrics and dicky clutches, problems an enthusiast could live with but a stranded industrialist running late could not. Bustling Blue Oval men bristling with can-do efficiency, all clipboards and beady eagle eyes, were conspicuous in Modena and Maranello by April. Enzo was ready to sell.

The offer was $18 million for 90 per cent of the stock and all future rights. It was a good deal – more lucrative than the one Enzo would eventually agree with Fiat – but there was a sticking point: Ford wanted to dictate the racing programmes. Enzo refused to budge and eventually left 14 angry men agape around the table. Negotiations were through. This affront not only seriously pissed off ‘Hank the Deuce’, it gave Enzo a shot in the arm.

Ferrari founder appreciated Le Mans’ commercial advantages, rather than its sporting merits

Getty Images

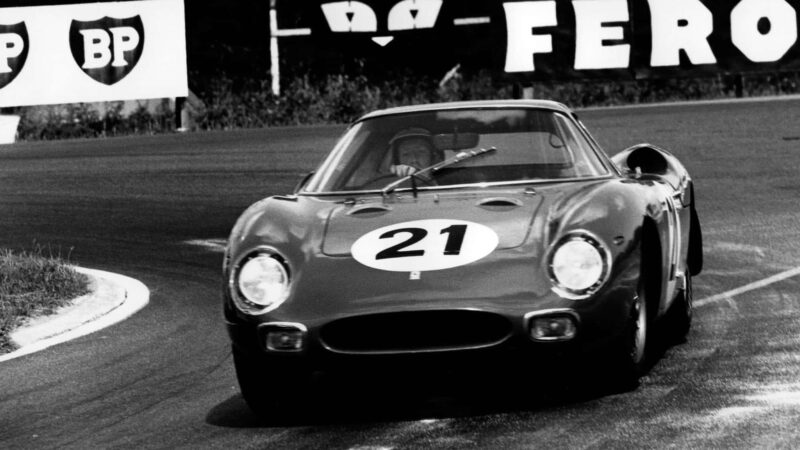

Ferrari’s 1963 win, for Italian dup Lodovico Scarfiotti and Lorenzo Bandini, was unopposed but reliant on others’ misfortunes. Sharing with Surtees, Willy Mairesse lost the lead when a half-shut fuel cap caused a hospitalising fire the first time he braked after a stop. Ferrari could still be slipshod.

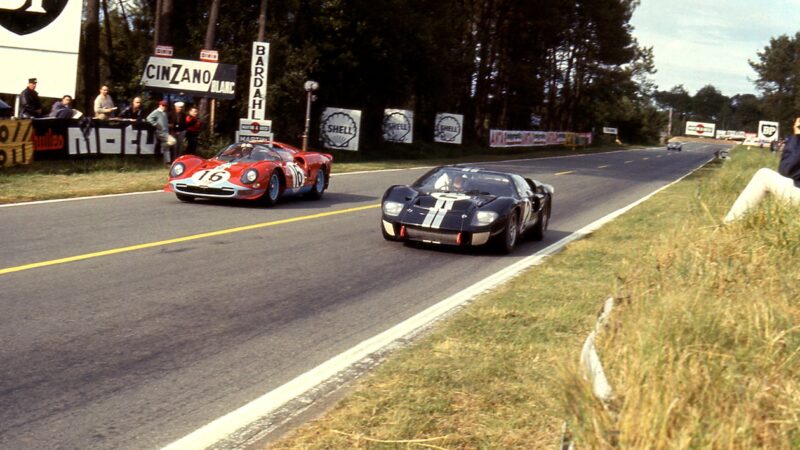

Ford’s arrival in 1964 altered the dynamics. Ferrari called on its privateers to help run six full-shot prototypes against three GT40s built, prepped and run by John Wyer’s Ford Advanced Vehicles of Slough. Richie Ginther, another American relieved to have left the Scuderia – he was searched on the way out! – blew by three Ferraris on the Mulsanne Straight to lead the early stages, and team-mate Hill set the race’s fastest lap. But ultimately Ford was let down by its Italian Colotti gearbox and victory went to the second-tier Ferrari of Nino Vaccarella and Jean Guichet.