The terrible irony was that Jimmy Clark did not want to be there at all. The original intention was for him to drive Ford’s dramatic new F3L sports car in the BOAC 500 endurance race at Brands Hatch that weekend. But there was some misunderstanding with Alan Mann Racing, which was responsible for filing the entries, and by the time that was sorted out Clark, miffed by the muddle, had felt duty-bound to honour his usual commitments to Colin Chapman and Team Lotus. He would compete in the Deutschland Trophy, a round of the European Formula 2 Championship.

His relationship with the imaginative but mercurial designer was perhaps the deepest between any driver and team principal in the sport’s history, and was based on mutual respect. It had been Chapman who gave Jimmy his break into Formula 1 in 1960. At that time he was raw and naïve, still very much the self-contained Border farmer and far from the polished Europhile he would become. He and Chapman matured together, learned from one another. In some ways they even complemented each other. Jimmy’s innate speed and God-given ability to get the best from his machinery was legendary, but certainly by today’s elevated standards he was not a technical driver. But he had an intuitive feel for what a car was doing and a clear-thinking ability to express that feeling directly to Chapman, whose fertile mind would then figure out what they needed to do to effect a cure or simply to make the machine go faster.

Chapman and Clark at Spa in 1962: team boss and star driver shared a strong bond

Jimmy, and his fellow World Champion team-mate Graham Hill, had been struggling all weekend at Hockenheim. It was part of the price you sometimes had to pay when you raced the lesser lights in such events, where so-called ‘graded’ drivers competed with less established upcomers. Brabham and Matra chassis were frequently a match for the Lotuses, if not superior, but the previous year Jimmy had enjoyed success with the same 48 he was driving in Germany, and had shown Brabham-mounted F2 king Jochen Rindt the way home on a few occasions even if their equipment was not absolutely equal. The previous week he had been taken out of the Barcelona round of the championship after Jacky Ickx inadvertently rammed him, and observers remember Jimmy being uncharacteristically angry with the young Belgian. Now, he and Hill were in trouble again, thanks to the horrible weather. Their Cosworth FVA engines were misfiring intermittently, and their Firestone tyres could not generate sufficient heat in the cold, damp conditions.

Despite the problems, Jimmy had qualified seventh. Ahead of him were drivers such as Frenchmen Jean-Pierre Beltoise and Henri Pescarolo in their Matras, rising Englishmen Derek Bell and Piers Courage in their Brabhams, and German Kurt Ahrens in a similar car. New Zealander Chris Amon, in an otherwise healthy Ferrari that was similarly struggling with the same Firestones tyres, was sixth. Only Amon, with whom Jimmy had enjoyed some fabulous tussles early in the season on his way to winning the Tasman Series in Australia and New Zealand, was remotely in the 32-year-old Scot’s league. Like Juan Manuel Fangio and Stirling Moss before him, Jimmy was the unquestioned greatest driver of his era, the yardstick by which all the others were judged and, indeed, judged themselves. Those ahead of him on the grid that day knew they were only there because he had problems.

He had made his Grand Prix debut on June 5, 1960 at Zandvoort, and thereafter his performances on the track soon became part of racing lore. By Hockenheim Jimmy stood unmatched in terms of Grand Prix victories. His success in the South African Grand Prix at Kyalami, on January 1 that year, had taken his tally to 25 from his 72 starts, one more than the legendary Fangio. And, perhaps more remarkably, he had achieved them all in the same make of car, whereas the great Argentinian had been happy to switch from Alfa Romeo to Maserati, Mercedes-Benz, Lancia-Ferrari and then back to Maserati as he amassed his 24 wins. Perhaps both figures seem small beer to today’s fans, reared on Michael Schumacher’s 91, but there were far fewer races back then, and cars did not enjoy bulletproof reliability. Jimmy could attest to that: he won the World Championship in 1963 and ’65, but was robbed of the 1962 and ’64 titles by mechanical ill fortune in the final races. Crowning such achievements was his triumph in the 1965 Indianapolis 500, and even there he should have won the ’63 event too but for some horse-trading among the establishment, and there are still many who believe the organisers missed a lap that would have made him the victor in 1966, too.

Clark’s final grand prix victory in South Africa, 1968

DPPI

At the wheel, he simply shed all of his insecurities as a man and instead became a master in total control, yet the moment he stepped from the cockpit he would revert to his innate self-containment, which many mistook for shyness. He was uncomfortable in the spotlight, and frequently wondered privately to friends what all the fuss was about. He genuinely did not appear to understand his towering talent, but that is not to suggest that he was a naïve wallflower. He was a tiger at the wheel.

Derek Bell was still carving his reputation back then, and has never forgotten meeting Jimmy for the first time that fateful weekend, as both were staying in the Hotel Luxhof in nearby Speyer. He remembered feeling awed in his company over tea on the Saturday afternoon. Then Jimmy stunned him in a conversation over breakfast on Sunday. “He said to me: ‘Don’t get too close behind me when you come up to lap me, because my car is cutting out intermittently…’

“If Stirling Moss was my hero, Jim Clark was my idol,” Bell recalls. “I thought, ‘This is my idol saying ‘When you come up to lap me…’ It wasn’t easy to take in.”

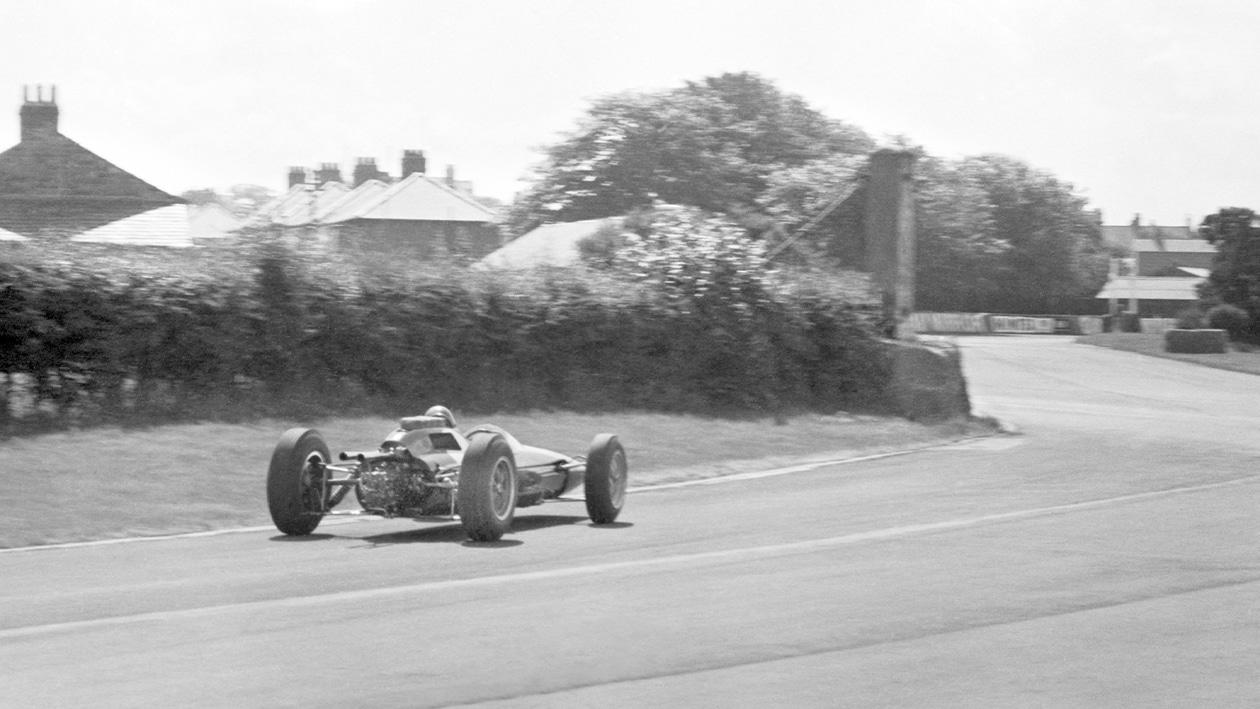

Even as they spoke, Lotus mechanic Dave ‘Beaky’ Sims was running the Lotus up and down the road outside the hotel, trying to cure the misfire. “The problem was, it was freezing,” Sims remembers. “There was a heavy frost. It was so cold it was affecting the fuel metering units. The drive belts were breaking. In the end I used boiling water. That cured it.”

Clark, the farmer, at home

Getty Images

There were indications early in 1968 that Jimmy was considering his future. He told Graham Gauld, his long-time friend and biographer, that he was thinking of cutting back on his racing, getting married, and settling back down on the farm in Duns, just north of the border with England.

His girlfriend, Sally Stokes, also recalled a similar conversation she had with Jimmy. “We had a telephone conversation shortly before he died, and he was probably talking about retiring and I can’t remember what I was saying, but then he said: ‘Well, what if I died? What if I got killed on the track?’ And I was so surprised and so jolted, because he’d never mentioned it in all the years I’d known him. And I was wondering if he actually thought about it and was considering retiring.”

Jackie Stewart, his great friend and the man who would inherit his mantle as the benchmark driver in motor sport, believes he would have carried on because, incredible though it might seem, Clark was still getting better as a driver. “For Jimmy, the easiest thing he did in life was sitting in a racing car. He was becoming more rounded. He was happy with what he’d achieved, but he was still insecure with his life because he didn’t know whether he wanted to be a farmer or a racing driver.”