Scheckter, who was winning the UM Formula 5000 series Stateside, returned to F1 in Canada in September, and qualified third, admittedly behind Revson. Sure, Peter was good, smooth and capable, but McLaren knew which way the wind was blowing. They wanted Jody for 1974, easing Revson into a third, Yardley-backed (Texaco/Marlboro would sponsor the other two) car to make way for Fittipaldi. Still grouching over their carambolage, however, Emmo vetoed Scheckter. A put-out Revson had already switched to Shadow, so Mike Hailwood landed the Yardley drive, and Denny ‘The Bear’ was out of the woods for one more year.

Fittipaldi and McLaren would win the titles, the team’s first, that year, justifying these choices, but did so via consistency and car-sorting prowess rather than speed. Emerson felt he had the best team, if not the best car, and because DFV-vs-Ferrari was at its most competitive, he (and the team) decided handfuls of points on bad days would be the key. They were. Just.

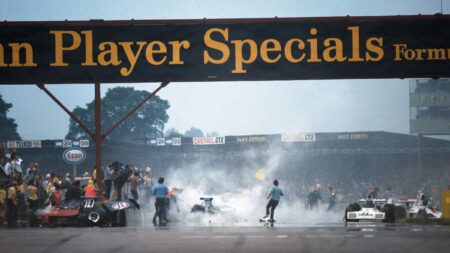

The next season was ultimately disappointing despite three wins, two of them admittedly garnered in foreshortened races at Montjuic and Silverstone. And despite an eventual second place for Emerson in the title race, he had seemed disenchanted in the early part of the year. So here’s the rub: no-one drove M23 as hard as rough-edged Jody did in 1973, until the equally fiery James Hunt rocked up in ’76. And had Jackie Stewart, maybe even Ronnie Peterson, been in the M23 in ’73, McLaren’s title wait would have been one year shorter. For the car was on the pace the moment it turned a wheel and was setting poles five seasons later.

US star Peter Revson took his two F1 wins in the M23

Bernard Cahier / Getty Images

Yet remarkably, it was Gordon Coppuck’s first F1 design. He had learned the ropes under Robin Herd on M7 (1968), been in cahoots with Jo Marquart on M14 (70), and had wowed Indy with his M16 while Ralph Bellamy penned M19 (’71). M23 was Coppuck’s response to the deformable-structure regs in force as from the 1973 Spanish GP. Tyrrell and Lotus doffed their caps to the wording, bolting and riveting onto existing cars; McLaren were more thoughtful, strategic. How much more they surely could never have guessed.

“We had always hoped M23 would be a two-year car,” admits Coppuck. “As well as meeting the new regulations, we wanted to build a much stiffer chassis. It was a bit of a risk in that the chassis extended right out to the extremities of the radiator duct, integral with the chassis, but it paid off.”

M23’s build was complex — its monocoque double-skinned 16 gauge aluminium sheet sandwiching injected foam — but at its core lay a rugged simplicity. An amalgam of M19 rear end and M16 wedge front and hipster rads, it was tidy, well-built and, crucially, possessed of a bigger footprint than the 72 and 005-006. It was, basically, F1’s way forward. A solid foundation upon which to pile two seasons of continuous, Fittipaldi-led development, from where to launch a feverish, Hunt-inspired title bid.