Top Le Mans moments 80-71: Wollek’s near-miss to the bottle top that saved Bentley

Our countdown of the 100 years of Le Mans highlights continues with a quadruple amputee racer, Gordon Murray’s side project, and a crash that took out three Fords

Getty Images

80 – 1998 Brilliant Bob’s final near-miss

Bob Wollek always said he could live without winning the Le Mans 24 Hours, that what would be would be. It didn’t look that way as he stood on the podium in 1998 after finishing second in a Porsche 1-2. Yet another opportunity to claim the one major sports car victory missing from his CV had gone, and there he was bawling his eyes out.

A clear Porsche 1-2 in 1998, but Wollek would miss out on ‘the big’ one for a final time

DPPI

It would be his last chance to win the ‘big one’ overall. He couldn’t have known that as he stood there, his emotions overflowing, though time was obviously running out for a driver who was now in his mid-fifties. That was probably the most remarkable aspect about a Le Mans career encompassing 30 starts and straddling six decades: Wollek’s best results came after he’d hit the big five-0. All but one of his six overall podiums at the Circuit de la Sarthe came when he had passed his half century. Wollek was a marvel, in that he remained at or near the cutting edge of competitiveness deep into middle age. He probably should have won Le Mans in 1995 driving a Courage-Porsche C34 with Mario Andretti among his team-mates and could have won in 1996 and ’97 at the wheel of the Porsche 911 GT1 and then the Evo version that succeeded it. The chance of victory in the carbon-chassis 911 GT1-98 that followed disappeared when team-mate Jörg Müller went off at the first Mulsanne chicane and damaged the floor during the night.

“Bob was a quick and determined driver,” recalls Allan McNish, who won that year with Stéphane Ortelli and Laurent Aïello. “I remember testing with him at Jerez, and I couldn’t get anywhere near his pace in the slow corners. He would float around them effortlessly. I gave up trying to match him in the slow stuff and just mullered it in the quick corners to try and make up time.”

Porsche’s withdrawal, initially a one-year hiatus announced at the end of ’98, and then a more permanent retreat that would end up lasting until 2014, meant there would be no more chances for Wollek to right the wrongs of his long Le Mans career.

79 – 2016 Quadruple amputee makes the grid

Frédéric Sausset belied his lack of experience as a sophomore racer when he made his Le Mans debut. That he performed so creditably at the wheel of a Morgan-Nissan LMP2 was all the more remarkable because he was a quadruple amputee. The Frenchman hatched a plan to race in the 24 Hours as he lay in his hospital bed recovering from a life-changing condition. He knew he needed a purpose in life and found it by doing the unthinkable.

78 – 1994 Norbert Singer’s final 962 brainwave

The race car turned into a road car turned into a race car… It was Porsche’s great racing architect who yet again sparked a winning idea, provoked by fears McLaren would take its new F1 supercar to Le Mans. Jochen Dauer’s 962 road car had been frowned upon by the factory, but now came in handy. Outside the spirit of the new GT rules? The ACO was piqued, but allowed the LM-GT just this once. The McLaren didn’t turn up (yet) and a seventh 956/962 Le Mans win – 12 years after the first – was bagged.

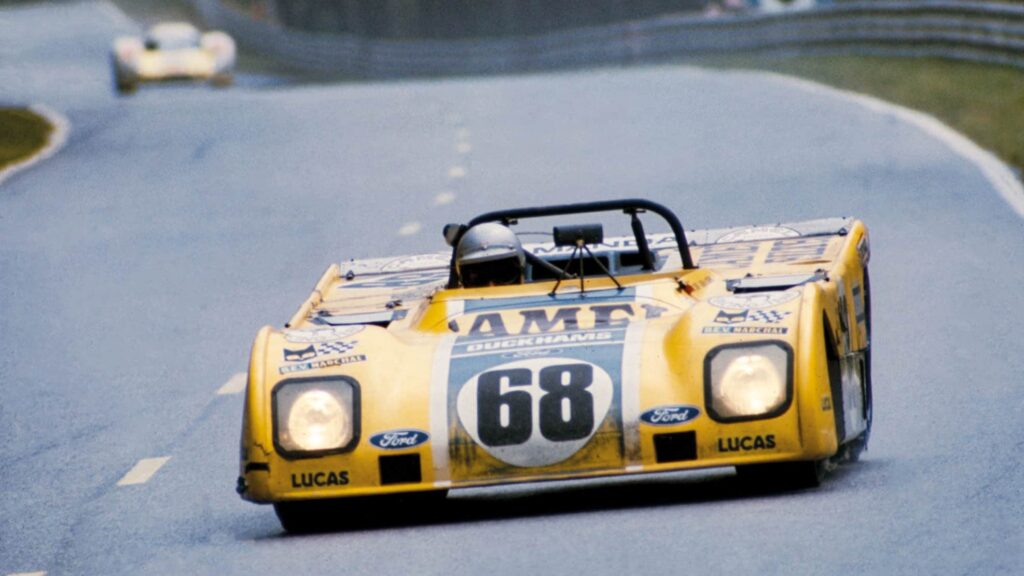

77 – 1972 Gordon Murray creates after-hours enduro special

Gordon Murray’s first successful competition car wasn’t an F1, but an endurance prototype commissioned by gentleman racer Alain de Cadenet (see also #67). In typically adventurous fashion, the charismatic ‘de Cad’ put faith in a young South African practically running the Brabham F1 design office on his own. After penning the car in the evenings following the day job, de Cadenet and Chris Craft drove the Duckhams Special to 12th.

76 – 2015 Hülkenberg guests – and wins

Contemporary grand prix drivers regularly competing at Le Mans had long since become a thing of the past when Nico Hülkenberg pitched up in a third Porsche 919 Hybrid LMP1 in 2015. But the race rookie went on to become the first driver to take time out from a Formula 1 campaign and win the 24 Hours since Johnny Herbert and Bertrand Gachot were part of the winning Mazda crew in 1991.

It would be wrong to say that Hülkenberg was somehow the defining factor in the extra Porsche’s ultimately-successful battle with the sister car shared by Mark Webber, Timo Bernhard and Brendon Hartley. But it was the Force India driver who began the charge to victory as the sun set on Saturday evening.

He moved the car up to second ahead of Webber during his second race stint at Le Mans and then Nick Tandy and Earl Bamber continued the good work. Their Porsche had the edge over the sister car in the cooler conditions of the night, and by the time the sun came up they were established out front in their internecine battle.

When the challenge from the last of the trio of Audis wilted around 7am, an historic win was more or less in the bag for Hülkenberg and Porsche.

75 – 1967 Ford’s three car wipe-out

Of the feuds within Ford’s megabucks programme none were more intense than that between AJ Foyt and Mario Andretti. The former, leading, became incensed by the latter’s aggressive charge in the rain at night. Thus it was heated even before Andretti’s more cautious co-driver pitted twice to complain about the brakes. Reinstalled, Andretti slammed into a bank the first time he hit the middle pedal; a pad had been installed backwards. Cresting the rise before The Esses, Roger McCluskey hit the sister car amidships. Jo Schlesser followed. Three 7-litre Fords were out in one swoop; and a fourth punctured on the debris. McCluskey commandeered a marshal’s car to get Andretti, who broke ribs, back to Ford’s medical unit.

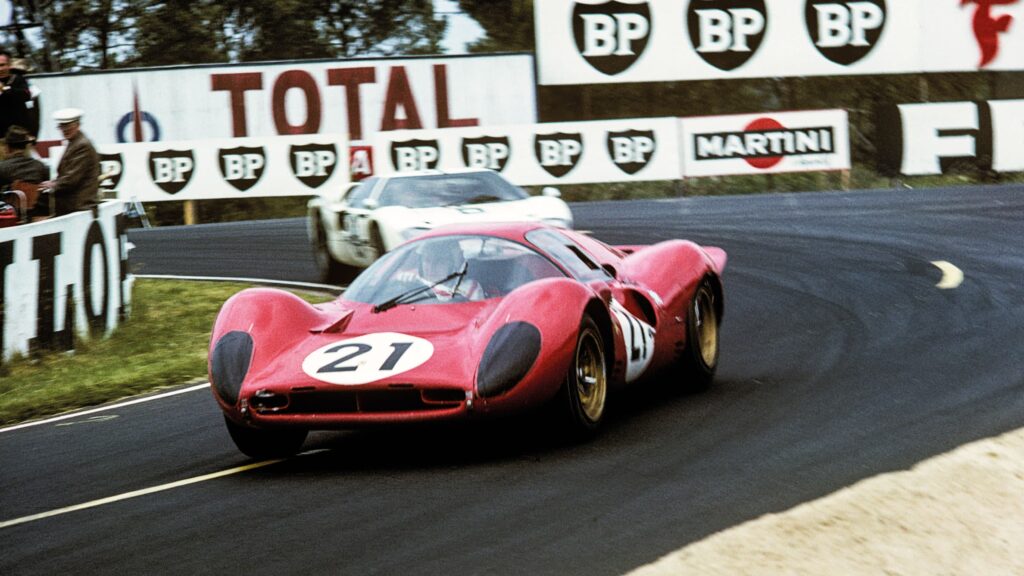

74 – 1967 Gurney vs Parkes

Though overpowered and outnumbered, Ferrari had hoped to outlast its arch rival. Indeed, only one Ford stood in its way of a 10th victory by early morning. Unfortunately, it was several laps up. Triggering a dice would be the Scuderia’s last roll: Mike Parkes was its agent provocateur; and Dan Gurney his target. “He was all over me, flicking his lights, trying to get me to drive harder,” said Gurney. “I knew what he was trying to do, so I stopped on the grass at Arnage. He stopped behind me and we sat there for 12-15sec. Finally he gave up and pulled back onto the track. About four laps later, I caught him and drove by.”

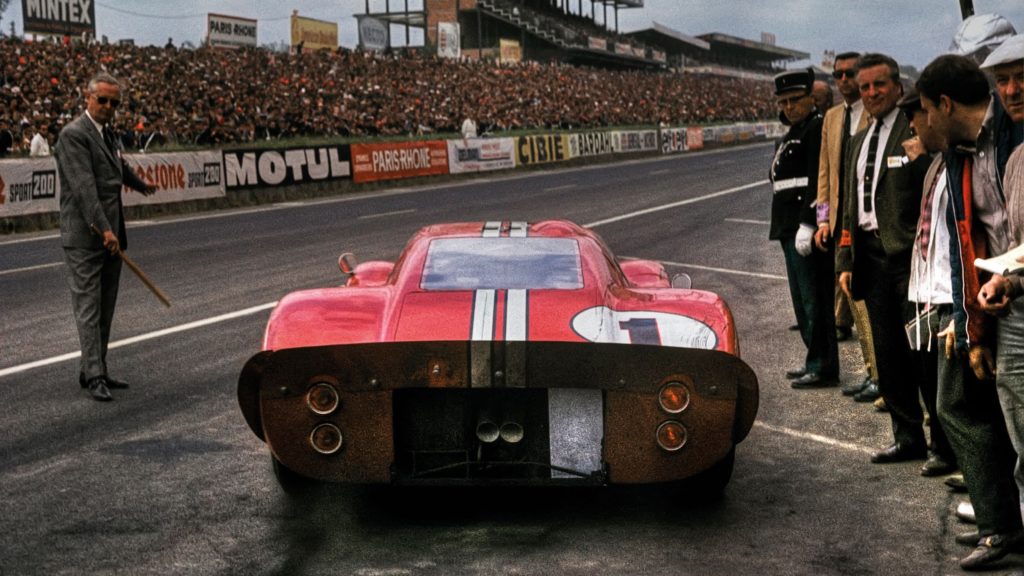

73 – 1967 Foyt wins on only visit

A predicted weakness of Ford’s $6 million men was a lack of prior experience among its drivers: Mario Andretti and Mark Donohue had been to this 140mph track lined by trees just the once – both retiring early in 1966 – and Lloyd Ruby, Roger McCluskey and AJ Foyt not at all. Dan Gurney, in contrast, had been trying to win here since 1958. To have paired him with Foyt was reckoned unwise by some: two bulls in the same field.

Yet this dynamic duo took the lead during the second hour and held it to the finish to score the first, and only, all-American win – at a record 135.48mph average.

An all-American victory for the ages! AJ Foyt (left) and Dan Gurney complimented each other in Ford’s GT40

Getty Images

“AJ kept his end up real well and was a good team-mate,” said Gurney. “He was an excellent politician and was constantly fighting our cause; we called him ‘Cassius’ because he always had a point to make. There were some fierce rivalries within the team: there was the Holman Moody side, the East Coast boys; then there was us, the Westerners, under the auspices of Carroll Shelby; plus we were on Goodyears and the others were on Firestones. That car certainly surprised me. Not that it was quick but that it was capable of winning the Index of Thermal Efficiency as well as the race itself. That was partly due to the fact that AJ and I didn’t have to push it to its limit in order to win.

“It had a smooth ride and, once we had sorted out its balance by adjusting the rear spoiler, it gave you a relaxed run down the Mulsanne Straight, which was very important. It had a slippery shape and adequate power and we were doing 213-215mph, taking the Mulsanne Kink flat: no trouble. I remember fitting my belts on about the second or third lap after the start and having to drive using my knees. It didn’t have power steering but it was no big deal to pull that kind of stunt.

“The only real problem we had was the brakes. They were in trouble: a large, heavy car running at high speeds on a track that had some big stops. But if you were sensible and looked after them, they were OK. AJ and I were well matched in that respect. There were some small differences in brake wear and mpg, but we liked the same set-up.”

Cut from the same cloth, neither man would see a need to return. Job done.

72 – 2011 McNish and the great escape

The race was still young when Timo Bernhard ran wide at Dunlop, allowing Allan McNish’s sister Audi to slice in front, and immediately up the inside of a Ferrari GT car – except its driver Anthony Beltoise hadn’t seen the R18 coming. The resulting contact sent the Audi slamming backwards into the tyre barrier and up into the air. Watch it back now and it still defies belief how the disintegrating missile didn’t tip over the top and wipe out the scattering photographers and marshals. And what about that errant bouncing wheel? Too close.

Terrifying scenes in 2011. The ducking photographer is Peter ‘Pedro’ May, who said: “I just threw myself to the ground. But my first thought afterwards was ‘I hope Allan’s OK’”

71 – 2001 Bentley’s bottle-top podium

It was a toe-dip, the first of a three-year campaign. Testing of Bentley’s new EXP Speed 8 had been severely hobbled by a delay in signing off the use of Audi’s engine and the car didn’t run in full spec until three months before the race. It had run instead with an old Ford DFR. Nor had the team tested in wet weather before Le Mans, meaning its bespoke Dunlop tyres were unproven.

Then, at the Test Day, Martin Brundle posted the third-fastest time despite it being, by his own estimation “a crap lap”. Eyebrows were raised at Bentley’s engine supplier, whose works R8s had been expected to conquer all. In qualifying for the race itself Brundle couldn’t get within two seconds of his former ‘crap lap’ time. Much muttering and spinning of conspiracy theories was heard down Bentley way. Then Brundle looked at the grim forecast and said, “if this is true, we might as well go home now.”

A literal ‘50p part’ saved Bentley’s bid for a Le Mans podium in 2001

Getty Images

Yet the team worked the weather well and, briefly, Brundle led as all around him lost their heads. It was not to last. Water forcing its way into the gearshift actuator, stranded the car in the night. But when it happened to the second car, it got stuck in second rather than fourth gear so was able to struggle back to the pits where the top of a bottle of mineral water was positioned to stop the flow of water. Driven by Andy Wallace, Eric van de Poele and Butch Leitzinger, they stormed back through the field to finish third, a podium for Bentley after 71 years away. Many who were there on both occasions said the moment was more memorable than the victory that came two years later.