Cosworth DFV’s second life: its success outside F1

The Formula 1 wins tally for Cosworth’s DFV topped 150 but as Gary Watkins writes, away from the GP world this Ford-badged V8 packed a punch in a variety of series

DPPI

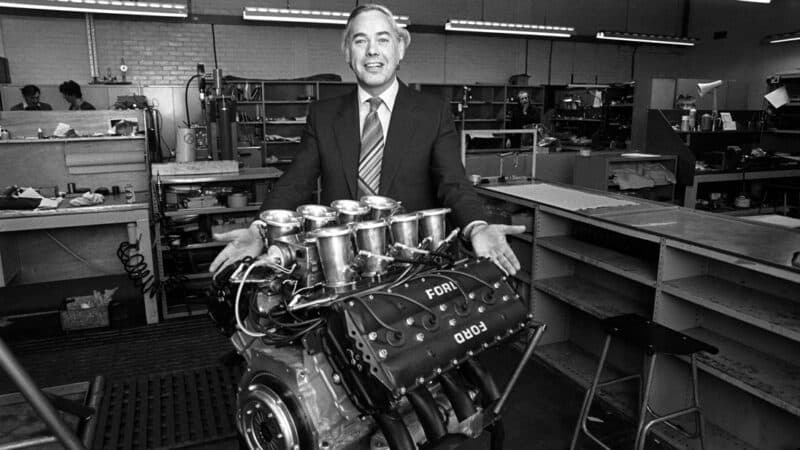

Keith Duckworth and his team at Cosworth designed the Ford DFV for one task and one task only – to win in Formula 1. One hundred and fifty-five world championship victories over three decades says they didn’t do a bad job. Yet the Double Four Valve turned out to be much more than a successful grand prix engine, despite its creator’s reticence – hostility even – towards the use of his masterpiece in other disciplines.

When famed sports car team boss John Wyer revealed that he intended to go to the Le Mans 24 Hours with a DFV in the back of a new prototype bearing the Mirage name in 1972, Duckworth told him not to bother. Parnelli Jones’s idea to put a turbo on the DFV for IndyCar racing was met with scorn, and when the team owner ploughed his own development path with the engine, Cosworth didn’t make life easy.

Keith Duckworth with his Double Four Valve in Cosworth’s Northampton base.

Alamy

The successes of the DFV in sports car and IndyCar racing, first under the auspices of the United States Auto Club and then CART, says Duckworth got it wrong when it came to his original stance on broadening the DFV’s application. Not only did the Cossie triumph at Le Mans twice, but what became known as the DFX won the Indianapolis 500 10 times on the trot between 1978 and ’87.

The story of Duckworth pooh-poohing Wyer’s plans for the DFV is best told by Derek Bell, who would give the DFV its maiden success at Le Mans paired with Jacky Ickx aboard a Gulf Mirage GR8 in 1975. He’ll even do the voices in his recreation of their reputed exchange: drawled tones for the team boss versus bluff inflections for the northerner who drew the engines. “John said, ‘I say Keith, I’m thinking of taking the Cosworth to Le Mans,’” recounts Bell. “Duckworth’s reply was, ‘I wouldn’t go, lad.’”

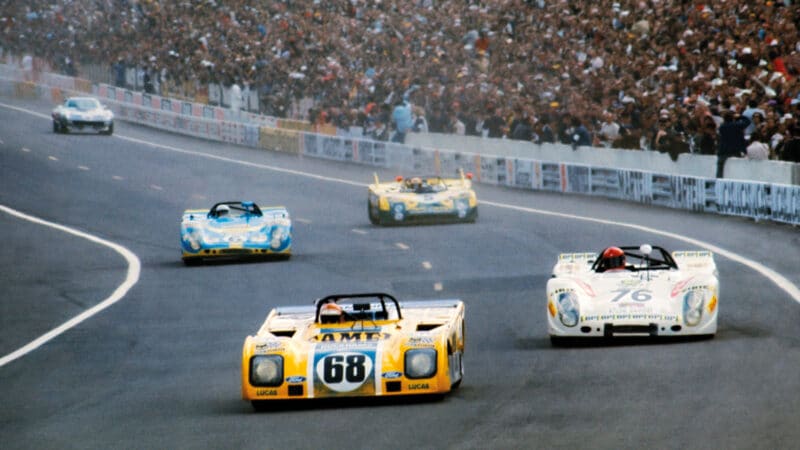

While the Matra V12 reigned at Le Mans from 1972-74, the DFV was making strides – Derek Bell and Mike Hailwood were fourth in this Gulf GR7

Getty Images

John Horsman, Wyer’s long-time engineering chief at JW Automotive and subsequently the driving force behind a team with the words Gulf Research Racing Company above the door, didn’t remember it any differently in an interview with this author in 2017, three years before his death aged 85.

“Keith might have suggested more than once that we shouldn’t waste our time,” recounted Horsman. “He certainly knew the shortcomings of the engine. I wouldn’t say he was against the DFV being used in sports cars, but he wasn’t very keen on it.”

Horsman was all too aware of the problems his team faced. It had put a DFV in the back of its short-lived M3 Mirage of 1969, the second sports car to run one after Alan Mann Racing’s beautiful yet ill-fated Ford 3L or P68 of the previous year. Using the DFV, he explained, was “needs must”, even if there was a brief flirtation with a Weslake-developed V12 paid for by Ford. The Porsche 917s JW had run in 1970 and ’71 had been legislated out of the World Sportscar Championship and Gulf Oil vice-president Grady Davis wanted a new design to chase victory at Le Mans under the latest rules limiting engine capacity to 3 litres.

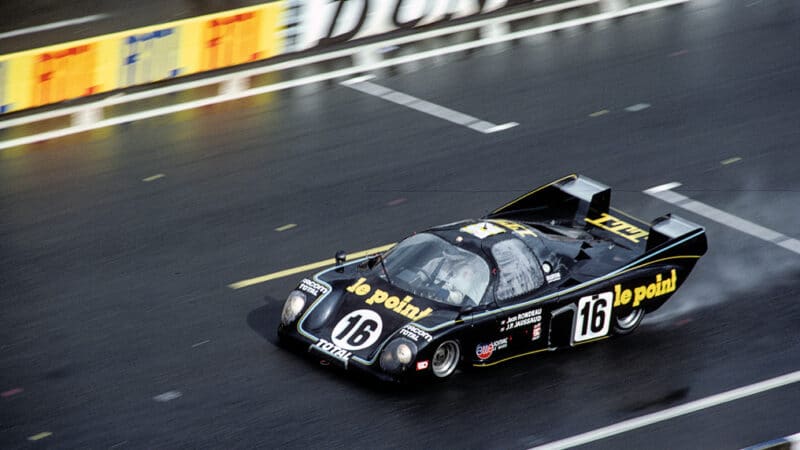

In the rain, Jean Rondeau fended off Porsche to win Le Mans in 1980 in his M379B – another victory for the DFV.

Getty Images

The nickname coined for the DFV during its early endurance racing exploits explains Duckworth’s reticence and Horsman’s apprehensions. The flat-plane crank engine became known as the ‘Ford Vibrator’. Its shortcomings as a long-distance engine had been reinforced right at the start of the Gulf programme: the new Len Bailey design shook the spindles off its gauges on the car’s rollout at Silverstone in early 1972. Bell remembers the padding being vibrated out of his seat insert at the Österreichring later that year. He had to brace himself against the side of the tub and eventually threw up.

That came two weeks after the team’s no-show at Le Mans. “The car was too new for the 24 Hours,” reckoned Horsman.

The M6 belatedly made it to Le Mans in ’73, just a month after taking its first world championship win at Spa with Bell and Mike Hailwood. The victory wasn’t the omen it might have appeared. Neither entry finished Le Mans, the car Bell shared with Howden Ganley only getting 29 laps into the race before major transmission repairs were required.

Prototype Ford P68

Alamy

Gulf Research had swapped from Hewland to ZF transmission for the French enduro. But the box that served JW so well in the back of its winning GT40 in 1968 and ’69 fell victim to the vibrating Cosworth lump. The input shaft broke, and ZF’s solution was not to beef up the component, but to make it smaller. “They told us it would allow it to twist and flex,” explained Horsman.

A revision of Bailey’s roadster, now dubbed the GR7, did make the finish of Le Mans in ’74, though Bell and Hailwood were 20 laps down on the winning Matra in fourth position. The French manufacturer was gone 12 months later, which should have turned the race into a Gulf Mirage vs Alfa Romeo confrontation. The Italian manufacturer, its T33/TT/12s now run by Willi Kauhsen, had notched up a sequence of five WSC victories pre-Le Mans with Bell among the drivers but again opted out of Le Mans. It wasn’t convinced its thirsty flat-12 could deal with a draconian new fuel limit imposed against the backdrop of the oil crisis.

Gulf Research slashed power from the Cossie to something under 400bhp even with a slippery new bodyshape for the latest GR8. Against limited prototype opposition Bell and JW old boy Ickx, who’d written to Wyer asking to drive with the Brit, had it easy. They took the lead after the first round of fuel stops and never relinquished it on the way to a one-lap victory at the head of a Cossie 1-2-3.

Duckhams Special used DFV in ’72

It might have been more — the GR8 had been six laps up at the halfway mark — but for the vibrations. The exhaust broke and so did an engine mount. The DFV ran as a load-bearing member, but Bailey had designed a ‘comfort’ frame around it. “It ended up holding the car together,” recalled Horsman.

“Bell remembers the padding being vibrated out of his seat insert at the Österreichring”

Gulf axed its programme at the end of the year and sold out to US entrant Harley Cluxton. A runner-up spot at Le Mans followed, but by ’77 the cars had Renault V6 turbos in the back. Use of the DFV was growing, however. Jean Rondeau took a quartet of class victories in 1976-79 with the British engine powering machines initially known as Inalteras – after a wallpaper manufacturer! – before a switch to his own name. In 1980, the son of Le Mans finally triumphed in a Cosworth-powered Rondeau M379B shared with Jean-Pierre Jaussaud.

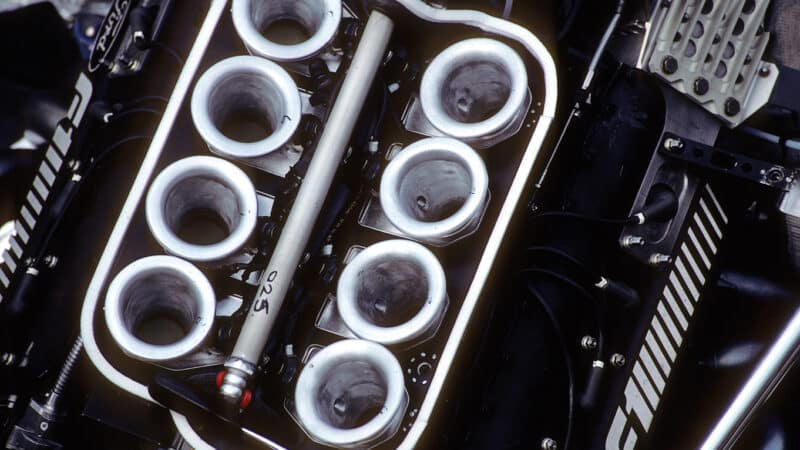

Cosworth developed an increased-capacity version of the DFV known as the DFL specifically for endurance racing in 1981. Initially of 3.3 litres capacity, it would subsequently be stretched to 3.9. The DFL would become a staple of the Group C2 category and was still racing at Le Mans as late as 1994. In addition to two wins and a further seven podiums, the DFV in all its forms notched up a total of 13 class triumphs at the Circuit de la Sarthe.

DFL powered Ecurie Ecosse C2 in ’87

Alamy

The vital statistics of the Cosworth in US single-seater racing make even more impressive reading. From its first win in the Pocono 500 in 1976 to its last at Meadowlands in 1989, it won 151 times in USAC and CART competition.

Vel’s Parnelli Jones Racing wasn’t the first team to look at using the DFV in Indycars. Penske Racing had undertaken a study in 1972/73 and Cosworth had drawn a crankshaft to bring the capacity of the DFV down to the maximum 2.65 litres. It appears that access to that crank was one of the factors that pushed VPJ down the same road.

Another was dissatisfaction with the ubiquitous four-cylinder Offenhauser turbo that could trace its roots back to before World War II. “We were blowing up engines left and right – we weren’t getting any satisfaction with the Offy,” says Jones.

Al Unser in a Parnelli-Cosworth, 1976

Getty Images

The next was the imposition of a turbo boost limit for the first time in 1974. The Offy was a monobloc design, sometimes known as ‘unit’ construction, which meant the head and block were one casting. Screwing up the boost wasn’t a problem. “If USAC hadn’t cut the boost, the Offy would still have been the engine to have,” explains Jones. “The reduction in the turbo pressure put everything in place to use the Cosworth.”

There was another contributor – VPJ had a Cosworth-engined car ready to go, of sorts. The VPJ4 F1 racer had made its race debut at the end of 1974; the Indycar known as the VPJ6 that made a fleeting appearance at the Brickyard in 1975 was only a lightly modified version of that Maurice Phillippe design. John Barnard was then lured from McLaren to turn it into an Indycar proper.

“The car Vel’s ran at Indy was little more than an F1 with a turbocharged DFV,” recalls Barnard. “The first thing I did was change all the spring rates – it was far too soft to run around an oval at 200mph.”

Unser leads Tom Sneva’s McLaren at Indy, ’77

Alamy

The car quickly evolved at Barnard’s hand into the VPJ6B. He also got pulled in the engine development programme, and ended up “drawing conrods, inlet manifolds, oil pumps and things like that”.

The Cosworth made its race debut in the B-spec car at Phoenix before the end of ’75 and had a first outing at Indianapolis the following May. Weeks later it took the Pocono victory with Al Unser driving. It was an important day in Cosworth’s history for more than the obvious reason. Parnelli had flown Duckworth over to the race to try to enthuse him about the programme. The team owner had initially had to buy complete F1 engines to turn into Indycar powerplants and was trying to forge a closer relationship.

“The vital statistics of the Cosworth in US single-seater racing make impressive reading”

Duckworth’s reaction to his engine, still known as a DFV, taking the win? He poached Parnelli’s Larry Slutter and Takeo ‘Chickie’ Hirashima and set them up in premises down the road from the team’s Californian base!

Unser took the first Cossie Indy win in Lola T500, ’78

McKlein

The DFX and the reworked DFS, incorporating developments from the 3.5-litre F1 DFR introduced in 1988, continued winning into 1989. It would remain part of the scene, even after Cosworth rolled out the all-new XB in 1992.

The DFR had been developed for F1 as a stopgap between the Ford Cosworth twin-turbocharged V6, the GBA used by Haas in 1986 and Benetton in ’87, and an all-new engine for the post-turbo era. The bespoke 3.5-litre HB V8 that came on stream in 1988 would provide the base for the IndyCar XB.

Normally aspirated power had returned to F1 in 1987 at the start of a two-year phase-in of the new 3.5-litre formula after little more than a season away, the DFV reincarnated as the DFZ in increased-capacity form. Tyrrell was among the first to race it, just as it had been the last to field what had become known as the DFY up to mid-season in 1985. But the bark of the Duckworth design didn’t disappear from the upper echelons of international single-seater racing. Far from it.

The engine found a home in a new category. Formula 3000 replaced Formula 2 for 1985. The idea of an F1 feeder series with 3-litre engines was proposed at the end of 1983 by Brabham and Formula One Constructors’ Association boss Bernie Ecclestone. Brabham wasn’t alone among FOCA teams in having a stash of redundant Cossies sitting around after switching to turbo power.

Cosworth’s V8 was an Indy 500 winner 1978-87, including Bobby Rahal’s victory in ’86.

His idea was quickly adopted by FISA, then the sporting arm of the FIA. It announced in December that it would run a series for so-called F3000 cars, though there was confusion about the future of the European F2 Championship. It appeared to be saying that machinery powered by 3-litre engines in chassis with flat-bottom aerodynamics would race alongside ground-effect 2-litre F2 machinery. Retractions, clarifications and then reaffirmations of support for F2 followed from the governing body.

What there was no confusion about, however, was the malaise facing F2. Honda had turned up in the European series with its V6 at the back end of 1980. It won its first title in 1981 and repeated the trick in ’83 and ’84. The powerplant had rendered the four-cylinder motors from BMW and Hart obsolete.

Michele Alboreto in a Benetton-branded Tyrrell-Cosworth, 1983 – the DFV’s F1 days were numbered

McKlein

“In order to stay competitive, we were slotting an engine in between practice and qualifying, and then changing it again for the race,” says Mike Earle, whose Onyx team led the BMW brigade with support from the German manufacturer in the final F2 years. “We were hanging on by our fingernails against Honda and it had become costly.”

Gabriele Cadringher, then boss of FISA’s technical department, believes that the motivation behind Ecclestone’s October ’83 proposal wasn’t just about off-loading engines that were surplus to requirements.

Eight pots soon had a new lease of F1 life

Getty Images

“I think he wanted a formula he could control,” says Cadringher. “It was part of what Bernie was doing, building his empire.”

FOCA would promote F3000 from its introduction in 1985, and within two years Ecclestone was brought into the FISA fold. He was announced as its vice-president of promotional affairs in 1987.

In 1987, the DFZ swept in, giving some oomph to Jonathan Palmer’s Tyrrell

Grand Prix Photo

But there was still water to flow under the bridge in early 1984 before F3000 was confirmed. Ecclestone may or may not have looked at going it alone outside of FISA’s auspices. He announced in mid-January a one-year delay of what might be described as a phantom series: there were no cars in existence at that point. His statement should probably be interpreted as political posturing as he strove to get his ideas across the line.

FISA appointed ORECA team boss Hugues de Chaunac to look into the future of F2. There was talk of using Group A production engines up to 2.5 litres, but in reality F3000, says the Frenchman, “was the only option”.

Pedro Lamy, pictured at the Nürburgring, claimed last DFV F3000 win at Pau in 1993.

DPPI

“The DFV had first competed in the British Hillclimb Championship in 1973”

When F3000 kicked off at Silverstone in March ’85 there were 16 cars on the grid, and all of them were powered by the DFV fitted with a Monk rev-limiter set at 9000rpm to increase mileage between rebuilds and therefore reduce costs. The engine would take its final European series victory in 1993, collecting a total of 55 victories.

Mike Thackwell in DFV-powered Ralt RB20 at Silverstone in 1985. The Kiwi was F3000’s first race winner

DPPI

By then the ageing engine was dominating another form of motor sport a long way from the rarefied heights of the international single-seater scene. The DFV had first competed in the British Hillclimb Championship in 1973 when friends and team-mates Sir Nicholas Williamson and David Good got hold of a pair of Cossies. Good commissioned Lyncar to build him a car, while it converted Williamson’s March 712S F2 into the Marlyn. Williamson would be the first DFV-engined winner, triumphing with the Marlyn at Barbon Manor. The Marlyn would win twice more before Williamson put the engine in a March 741.

Hillclimb legend Roy Lane would take over the March and won three times in 1977, though the title went to another driver with Cosworth horses. Alister Douglas-Osborn claimed the silverware with a car that had started as a Brabham BT38 F2 and then been reworked twice over by Pilbeam to become the R22. Yet the British Hillclimb crown wouldn’t fall to a DFV-based engine for another 13 years.

Frenchman Michel Ferté in ORECA March at Dijon 1985

DPPI

Hart F2 engines of ever-increasing capacity dominated the hillclimb scene in the ’80s, but by the end of the decade Martyn Griffiths, champion in 1979, ’86 and ’87, was sounding out company founder Brian Hart about more power. The engine builder didn’t try to up the game with his four-pot motor. He looked to another engine in which he had played a part. He’d helped Cosworth develop the DFR and managed to source an engine from Benetton that was barely a year old.

“Colin Hawker bought an engine from Tyrrell and installed it in his Ford Capri”

The hills were soon alive to the sound of the DFV. This is David Good pressing on in his Lyncar at Prescott in 1973

Alamy

“I guess I started complaining that I wanted more power,” recalls Griffiths, who shared his cars with Max Harvey. “It was Brian’s idea, his decision. He said, ‘Why don’t you have a DFR? I’ll develop it for you.’ It was all down to Brian. We had a good relationship.”

Pilbeam built Griffiths and Harvey a new MP58 to take the engine. Seventeen wins for the pair over 1990 and ’91 followed, with Griffiths taking both titles. “That engine in that car was a damn good combination, almost unbeatable,” says Griffiths.

On home soil, the DFV found its way to saloon car racing through Colin Hawker and his Capri

Alamy

David Grace would prove as much using the same car with a further two titles after Griffiths and Harvey had switched to rallying. It was the start of an admittedly short-lived Cosworth hegemony in British hillclimbing. Roy Lane and Andy Priaulx took the title with their MP58s powered by 4-litre DFLs either side of Grace’s pair in 1993 and ’94.

The DFV found a home in domestic racing, too. Essex Special Saloon racer Colin Hawker bought an engine from Tyrrell and installed it in his Ford Capri. He then transferred it to a VW 1600 Fastback lookalike built up around the first DFV-engine sports car to record a classified finish at Le Mans, Alain de Cadenet’s Duckhams Special. It was universally – and delightfully – dubbed the DFVW.

Hawker shifted the engine to the ‘DFVW’ in the mid-70s, displaying high resource on a low budget

Hawker’s whereabouts isn’t known, but Alex Hawkridge, boss of the Toleman Group that backed his efforts, remembers a resourceful engineer able to run an exotic piece of kit on limited funds.

“Scrap money was paid for the DeCad,” says Hawkridge. “Colin was a talented guy, who could turn his hand to anything. He rebuilt the engine using pistons that as far as the F1 teams were concerned were out of life. He had quite a wide circle of contacts, and was always going around with his hand out.”

Sir Nicholas Williamson in March 741 at Wiscombe ’76. Hillclimbing gave recent F1 cars a second wind

Bruce Grant-Braham

Hawker, says Hawkridge, “would be the first to admit that he wasn’t the world’s greatest driver”. But the DFVW was a regular winner in Special Saloons, though at its pinnacle in the Tricentrol Super Saloon Championship of 1975 and ’76 Gerry Marshall did most of the winning aboard ‘Baby Bertha’, the Repco-engined Vauxhall Firenza.

The car raced on briefly in the hands of Walter Robertson. But the engine in the back was far from an antique by the time the DFVW stopped racing in 1980. There were still many good years to come at Le Mans, Indianapolis and beyond.