Top Ten Le Mans Moments

With a century of the world’s greatest race to look back on, we catalogue the historic moments that helped define the legend of the Grand Prix de Vitesse et d’Endurance

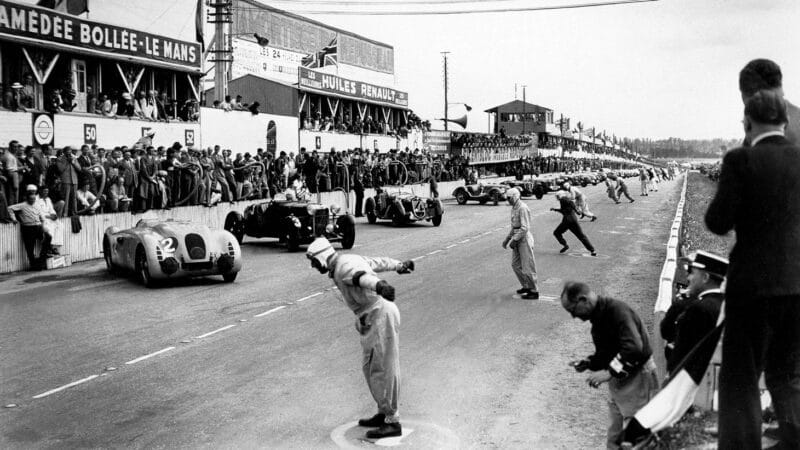

Less than three months from the start of World War II, drivers run to their cars at the 1939 Le Mans 24 Hours. It would be 10 years before the race would return

Getty Images

Taken from Motor Sport June 2023

The moments that helped define Le Mans’ legend: we’ve been through triumphs and tragedies from numbers 100 to 90. Here, as chosen by our panel of experts, are the top ten events that helped the race transcend the usual motor racing histories.

10 – 1951 Porsche opens its account

Porsche is the most successful marque at La Sarthe, but its debut was a battle. The diminutive 356 SL did win its class on its first outing in 1951, but nearly didn’t arrive at all when all three racing test mules were crashed. That left just chassis 063, which had started life as an abandoned aluminium shell left behind in Austria by Ferry Porsche after he switched to Stuttgart. Fitted with rear wheel covers and driven by Auguste Veuillet and Edmond Mouche, it finished 19th, winning its 1.1-litre category.

In the nick of time: after damage to its sister cars, the sole remaining 356 (46) took a win

Getty Images

9 – 1988 Jaguar rides its luck

The factory Porsche team is not an organisation for which one tends to feel too sorry, but there was one moment at Le Mans in 1988 when those watching could be forgiven for extending a little sympathy. With the race just four hours old, the lead Porsche was coming down the pitlane, powered not by its 800bhp, water-cooled, twin turbo, flat six engine, but by its starter motor and half the Porsche pitcrew. There was a huge cheer from the crowd.

Such a display of schadenfreude is perhaps more understandable when you consider Porsche was gunning for its eighth victory in a row and, to that end, had built a car full of trick bits and lightweight parts and crewed by its best drivers – Hans Stuck, Derek Bell and Klaus Ludwig – solely for that purpose. Jaguar, aiming for its first win in over three decades and which had walked the previous year’s championship but still managed to trip over its own shoelaces at Le Mans, now looked on for one of its five XJR-9LMs to prevail over the Porsches.

Jan Lammers’ first and only Le Mans win – and it was a corker

Getty Images

The source of the Porsche’s problem has been debated ever since. In its original race report, this magazine stated that “the reserve fuel pump failed to work properly”, but team boss Norbert Singer blamed the error on “Ludwig’s mistake of running out of fuel”. Bell is equally clear, not to mention rather more pithy: “The reserve? Well it worked perfectly well for the rest of the race…”

Porsche’s problem was not any lack of raw pace with which to recover the deficit, but a lack of fuel under the Group C regulations. But then on Sunday afternoon it started to rain and, left out on slicks when everyone else dived for wets, Stuck put on a masterclass of wet-weather driving those who saw it would never forget. Soon he was back on the lead lap and even hit the front when the Jaguar driven by Jan Lammers stopped for a new windscreen. Had the rain stayed Stuck might even have won. In the event, it dried up, and Lammers nursed a Jag suffering severe gearbox trouble to take one of the great Le Mans wins. Had the Porsche not run out of fuel? Who knows – the history of racing is written in ‘what if’ stories. But in the end it was Jaguar that ran out a worthy winner, breaking the distance record in the process and Porsche, just for once, was left wondering what might have been.

Winning Jaguar of Lammers, Andy Wallace and Johnny Dumfries fights the 962Cs

Getty Images

8 – 2008 Audi’s most unlikely win

Audi knew it couldn’t hold a candle to Peugeot in the dry, but it also knew that rain was forecast for the race. Its ageing R10 TDI had looked good against its French rival’s 908 HDi at the Test Day in wet conditions, so the task for Tom Kristensen, Allan McNish and Rinaldo Capello was stay in the hunt and wait for the weather to change. They drove the socks off the Audi and were sitting pretty when the rain arrived.

Getty Images

Getty Images

7 – 1969 Ickx beats Herrmann in closest (competitive) finish

It was a brave decision. The race was coming to a boil and yet JWA team manager David Yorke coolly called for a ‘15,000-mile’ service for the lead car: front pads and tyres, and hood-up fluids-and-belts check. Three minutes well spent: Jacky Ickx’s GT40 was now primed for its crucial final stint.

The rival Porsche 908/2, recovering from a half-hour wheel-bearing replacement and a collision with a sister car, could just about outrun the outdated Ford down the straight, but it was no match for it under braking for Mulsanne. Ickx usually crossed the start/finish line ahead. He did so with a few seconds remaining and the two swapped paint and positions on that final lap. Hans Herrmann considered a banzai move at Ford Chicane but decided not.

Ickx and Oliver won in GT40 #1075, which had also taken victory nine months earlier… The 1968 edition having been run in September. Here, they head the Matra of Nanni Galli and Robin Widdows

DPPI

6 – 1995 Murray’s magic McLaren F1 GTR rains…

It is one of the great unanswered and, indeed, unanswerable questions from this first 100 years of Le Mans. Would McLaren have joined Ferrari and (by default because it won the first) Chenard et Walcker as the only makes to have won Le Mans at the first time of asking had it not rained? It is impossible to say.

Lanzante-entered Kokusai Aihatsu Racing McLaren won in the hands of JJ Lehto, Yannick Dalmas and Masanori Sekiya

DPPI

But we know this: the McLaren F1 GTR was a competition development of a road car that had never been designed with racing in mind, and came with an essentially standard road-going transmission for which 24 hours of non-stop racing shifts had never been envisaged. That they’d be quick was not in doubt; whether they’d stay the distance was a very different question indeed. But rain it did. And rain and rain and rain, by some estimates for up to 17 hours, making it one of the wettest on record. And while that made life even more difficult for the drivers it took a huge strain off the McLaren’s driveline – and gave former Benetton F1 driver JJ Lehto a platform to shine. “I just loved the car, especially in the wet,” he said. “It had loads of traction, lots of torque – no problem.” Facing gearbox worries, terrible weather and far faster prototypes, albeit with smaller fuel tanks, McLarens finished in four of the first five places, including the one that matters most, proving the brilliant adaptability of Gordon Murray’s original design.

5 – 1969 Porsche presents 25 917s for homologation

Worried about thinning fields, the homologation figure for Group 4 sports cars was halved to 25 examples. Though Enzo Ferrari continued to grumble about it, his team was rumoured to be complying. This sparked Porsche to take a huge gamble for a small company whose racing and production development departments were one and the same. (Ferrari baulked at the cost and baled – until he sold a 40% stake to Fiat three days after the race.)

It nearly bankrupted the company, but Porsche’s crazy plan to create a full run of 917s in order to make the most of a rules loophole worked

DPPI

Design began in July 1968 – the 917’s 4.5-litre flat-12 used the same cylinder dimensions as the 3-litre eight and its frame owed a lot to the concurrent 908/2 – and chassis No001 was unveiled at the Geneva Motor Show on March 12, 1969 (yours for 140,000DM!). It caused a sensation.

But it was the line-up of the full complement in the forecourt at Zuffenhausen on April 21 that blew the mind. Though Porsche would come swiftly to realise that it needed outside help to sort and run this initially flawed car, undoubtedly this was the moment that altered its status forever: from admired to revered.

4 – 1997 Tom Kristensen receives a phone call from Joest

Blame Ralf Jüttner. It was Joest’s technical director who made a late decision to call on who would become ‘Mr Le Mans’, but had yet to step foot in the place. “That call was the very foundation of my whole Le Mans career,” says nine-time winner Tom Kristensen. “I never expected to be anywhere near Le Mans in 1997, then I got a call from Joest. I was to share with Michele Alboreto and Stefan Johansson. I signed just four days before the race. I’d never seen the track, and did just 17 laps in qualifying before the race. I was full of butterflies, preparing to impress the little team which was just 12 people then. Michele put the car on pole, and I got a new lap record. I remember Ralf coming on the radio saying ‘lap record, lap record. Now keep it steady, keep it steady.’ I realised, hey, if a German starts speaking English to me, then I’m doing a good job.”

The makings of a Le Mans legend: Alboreto takes the flag

Getty Images

For Kristensen, it was the start of a healthy habit

Getty Images

3 – 2016 Toyota’s last-gasp heartbreak

Toyota had long since been the nearly man of Le Mans when it had that elusive first victory wrenched from its grasp once again in 2016. It had come close in 1994, ’98 and ’99, and in 2014. But this time its loss couldn’t have been more dramatic. A victory over Porsche and Audi was lost when Kazuki Nakajima suddenly slowed with an engine problem with six minutes left on the clock.

The leading Toyota TS050 Hybrid Nakajima co-drove with Sébastien Buemi and Anthony Davidson had come out on top in a battle with the best of the Porsche 919 Hybrids. The car was a minute up when the Japanese driver lost power in sector one on its penultimate lap. Porsche believed the Toyota was running out of fuel — the TS050s had been going a lap longer than the 919s. But the problem was, in fact, a fractured airline between one of the turbos and its intercooler. Toyota tried to cure the problem when Nakajima, still just about in the lead, stopped on track opposite the team’s pitbox.

It was to no avail. So slow was his final lap – outside the six-minute maximum – that the car was unclassified.

With minutes remaining, disaster struck for race leader Kazuki Nakajima

Getty Images

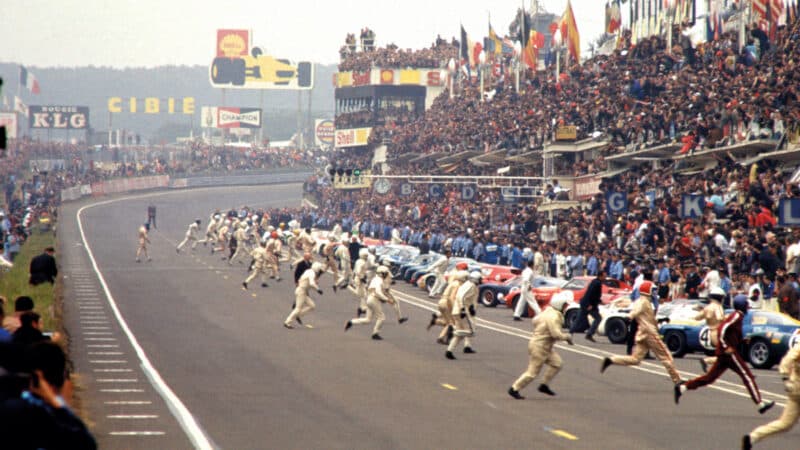

2 – 1969 Jacky Ickx takes a walk

There’s some irony that it should be Jacky Ickx who should end a grand old Le Mans tradition on the grounds of safety. Over in F1, he and Jackie Stewart grated regularly over the rising campaign that enough was finally enough. Not that Ickx was against improving his survival chances. He was just, as he put it, “conservative” in his approach. Yet here he was, at the start of the world’s most famous endurance race, posting a safety protest in the most sensational (yet naturally stylish) manner.

Aggrieved at the practice of drivers only doing up their belts on the Mulsanne – or even not at all after the running start – Ickx chose to walk across the track towards his Gulf Ford GT40 when the flag dropped. “In fact I did have to run the last few metres to my car, or I would have been run over!” he smiles. “A lot of people were upset with me, because that start was a great Le Mans tradition.”

In no hurry: Ickx saunters across the track to his car in an image that wouldn’t be out of place in Hollywood. The traditional running start was dropped a year later

Getty Images

But his point was proven in the darkest manner just minutes later when John Woolfe, his belts still undone, lost control of his Porsche 917 at the high-speed kink at Maison Blanche and triggered a multi-car accident. Woolfe died in the crash, and with him went the signature running start. Not before time.

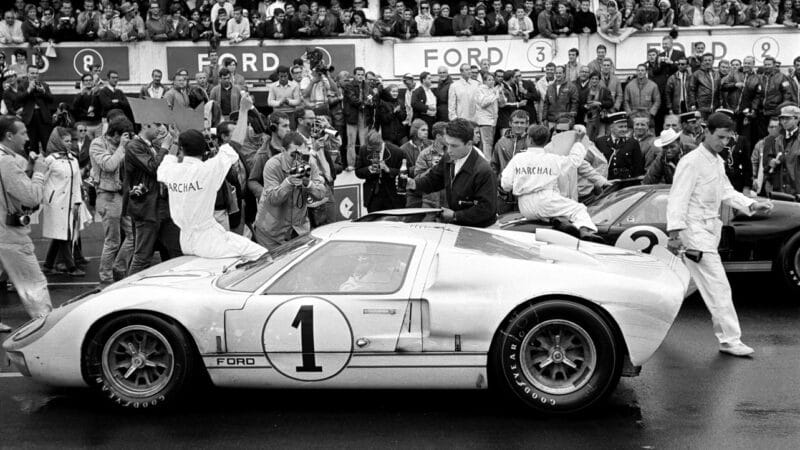

1 – 1966 Ford’s botched formation finish

Ford dominated the Le Mans 24 Hours race in 1966, winning it for the first time, and taking all the podium places with its updated MkII and stellar driver line-up. But instead of euphoria on the podium, Chris Amon and Bruce McLaren, who were classified first, were strangely subdued.

The pair had inherited victory from fellow Ford driver Ken Miles in car no1, who had earlier pulled out a lead of almost four laps over Amon and McLaren in car no2, before being ordered to slow down by the team, in order to engineer a dead-heat finish, and a powerful photo opportunity.

Miles thought he had won — as did the PA commentator — but it was no2, that was classified first, after whispers of conspiracy and sabotage. The moment has gone down in Le Mans lore and become one of the defining images of the race.

Miles and Denny Hulme should rightfully have won Le Mans in 1966, but for team orders

Getty Images

The full extraordinary tale is told in the book, Twice Around the Clock: The Yanks at Le Mans. What follows is an edited extract from that title.

When Ken Miles brought his car in for service and a driver change, he was informed of the plan. Miles was crushed. And furious. To him, this was revenge by those at Ford who didn’t like him. Busy with the car, Charlie Agapiou heard none of this, but when he looked up, immediately he knew something was wrong.

“Ken said, ‘They don’t want me to win the race. They want the Amon/McLaren car to win.’ I said, ‘Ken, what are you talking about? You’re miles ahead of them, how are they going to win the race?’ You gonna’ stop on the back chute or what? That’s impossible.’

But Miles was told the dead heat finish had been okayed by the ACO. To refuse to cooperate would mean the end of his career with Ford, so grudgingly, he agreed to go along with it, perhaps even believing that he had one or more laps in hand and that it would be for appearances only. But had that lap advantage disappeared with a suspect brake disc change?

Earlier, Hulme had brought their car in for scheduled brake change. Multiple sets of bedded-in rotors (discs) were prepared in advance by the crew chiefs of each car.

The new rotors were fitted and Miles took off for his stint, still laps ahead of McLaren. But then, trouble. Miles brought the Mk II back in the next lap. Agapiou was there. “Ken said, ‘I’ve got a vibration, a brake vibration.’ I said, ‘It can’t be a brake vibration, it must be the tyres.’ He said, ‘I’m telling you, it’s a brake vibration.’”

Knowing the rotors had been bedded in, Agapiou threw on a new set of wheels and tyres and Miles was sent out. Only then did Agapiou learn that the rotors he’d been given were not in fact the ones bedded in for Miles’ car. Those had been taken by the McLaren crew. There was no time to find out why. Miles was on his way in again, and another set of rotors had to be fitted. Agapiou was livid: “We ended up having to get two more rotors and hoping they were okay. Ken lost close to two laps, I think. All this poncin’ around, because McLaren’s crew chief, who was a good friend of mine, didn’t take the time to bed rotors in and put them aside for when his car came in. And McLaren ended up with our rotors.”

Henry Ford II

Getty Images

Thinking about it later, Agapiou suspected foul play.

“Ken was close to four laps ahead of McLaren. So there was no way he could have just slowed down for four laps. It would have looked stupid with the bloody press. I don’t know what went on, but he lost a ton of time with those two stops.”

“The ACO changed their mind – and notified Ford officials – there could be no dead heat finish”

In any case, the fix was now on near the end of the race. McLaren and Miles were told they’d finish in a dead heat and that both would be declared winner. What no one was told was that the ACO changed their mind – and notified Ford officials – that there could be no dead heat. As instructed, Ken Miles slowed to let McLaren catch up on the final lap, and for Hutcherson in his and Bucknum’s third Mk II.

As they approached the actual timing line, short of where the flag is thrown, Miles and McLaren seemed to be nearly side by side before Miles inexplicably checked up, allowing McLaren to surge ahead – then Miles pulled forward again.

It’s fair to say that, like the French P.A. announcer, most initially believed Miles had won. He’d led so much of the race and obviously slowed to let McLaren and Hutcherson catch up at the end, and when Hulme climbed aboard, their No. 1 car certainly looked the winner. Although first back to the podium, the No. 1 car was stopped and officials waved the Amon/McLaren car ahead – as the P.A. announcer now proclaimed them the winners. And so it stood, with an almost uncomfortable McLaren and Amon and a joyous Henry Ford II on the podium, joined only later by Miles and Hulme. [Carroll] Shelby was unequivocal about the situation.

The muted, and awkward, podium

Getty Images

“Ken Miles was way ahead of the race. He would have been the only man in history to win Daytona, Sebring and Le Mans. He should have won it.”

Agapiou, too, remained adamant that his friend was robbed, and pulled no punches as to where the blame lay: “He did exactly what he was told, and at the end, he slowed down all over the place to let McLaren unlap himself. He followed his orders and then he got f***ed. That’s what happened.”

It was a bitter irony that two months later Miles was killed testing a prototype of the designed-and-made-in-USA Ford racer with which Briggs Cunningham’s dream of an all-American victory at Le Mans with American drivers would be realised.

Extract from Twice Around the Clock: The Yanks at Le Mans